Transcription Project Completed – thanks to our incredible volunteers!

After a successful call for volunteers back in April to help transcribe letters from the earliest days of the profession, we have now published the results of our Volunteer Transcription Project – and they are pretty amazing!

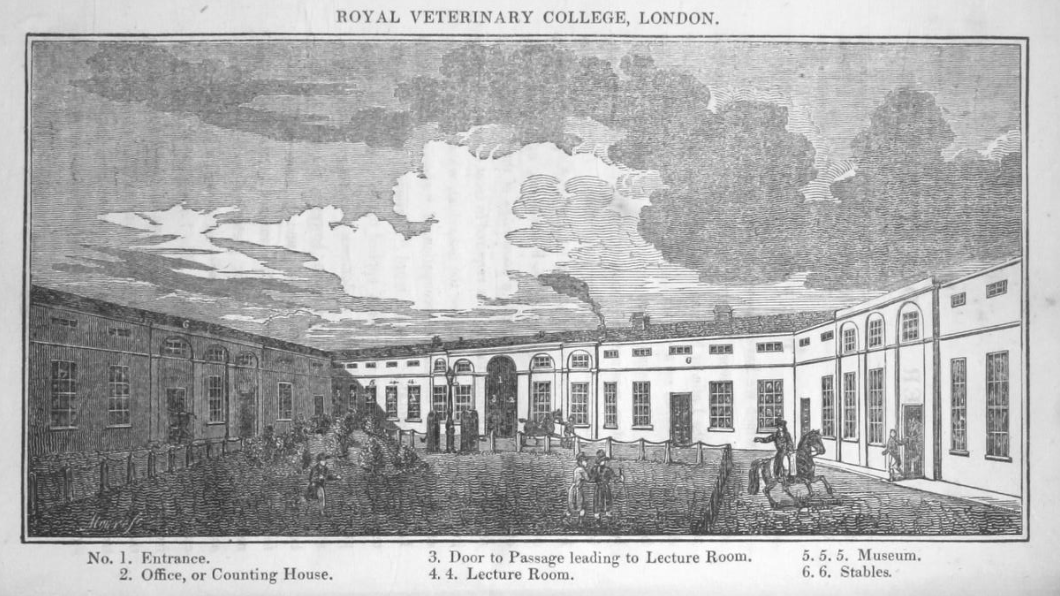

All the letters, which were written in 1840 in support of a petition that paved the way for the formation of the RCVS, and their full transcriptions can now be accessed on our website.

We were very lucky to have contributions from 51 people over six months, fully transcribing 256 handwritten letters, to make them more easily accessible for a 21st-century reader. Here we share some insights and thoughts about the process from our fantastic team of volunteers.

So why did people volunteer?

One reason we were able to attract such a large number of contributors was due to many veterinary staff being put on furlough during the initial lockdown period, and therefore having more time to indulge their existing historical interests.

Debbie Summers, an RVN working in Kent, and already an avid collector of Victorian postal history, told us “I was immediately interested in this project and had some skill in deciphering Victorian handwriting which I thought could be of use.” For retired small animal vet Carol Young, the project was a way “to reconnect however slightly with the profession I still missed”. Other volunteers, such as Linda Lowseck, retired former CVO of Jersey, had a more personal connection to veterinary history, as her great-grandfather qualified as vet not long after these letters were written.

However, previous historical interest was not essential. Claire Coulthard, an RVN working in the North West of England, told us she hated history at school, but during the project realised she was “becoming interested in the letter’s contents and the people who had written them.” By the end of the project, Claire had transcribed 16 letters in the collection, more than any other volunteer.

Happily, this project just seemed to scratch an itch for some people. Ginny Kunch, a veterinary practitioner from Oregon, USA, said she was “going a bit stir-crazy when I found this project online… Also, I’m a sucker for quill and ink.”

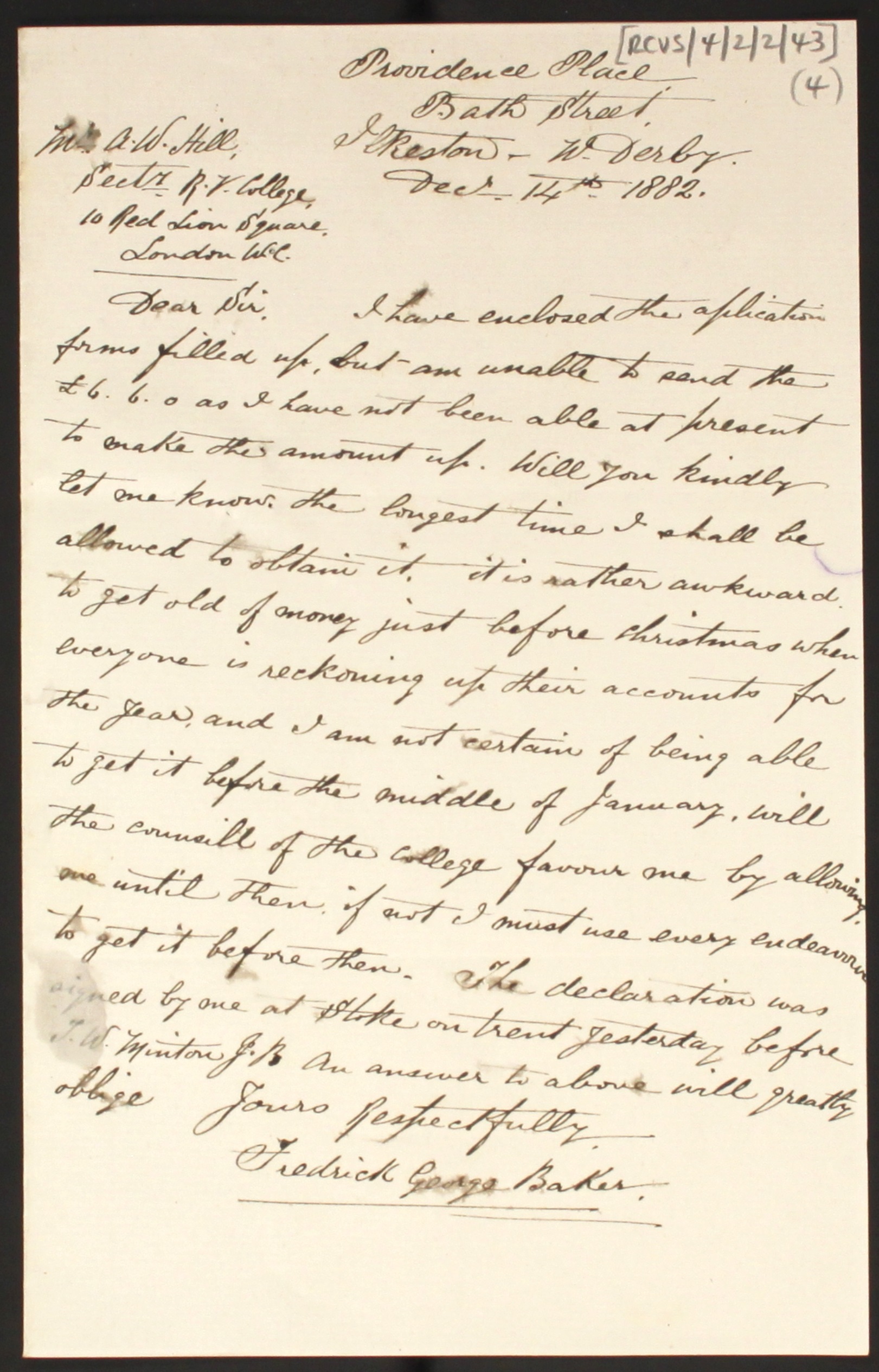

Letter from Thomas Brown, Manchester, of the 6th Dragoon Guards

Learning how to transcribe

Most of the volunteers were entirely new to reading historical material, and so were eased into the task with shorter letters, (relatively) clearer handwriting, and tips and tricks about deciphering tricky words. Debbie Summers used a combination of perseverance and luck – “Sometimes [the right word] would ‘appear’ after a while of pondering, other times it was a best guess! I have definitely improved my skills in this area from working on this project!”

Soon, however, many of the participants were up and away and asking for longer and more challenging letters. It turned out that many of the vets and vet nurses who joined us had lots of experience interpreting badly written practice notes!

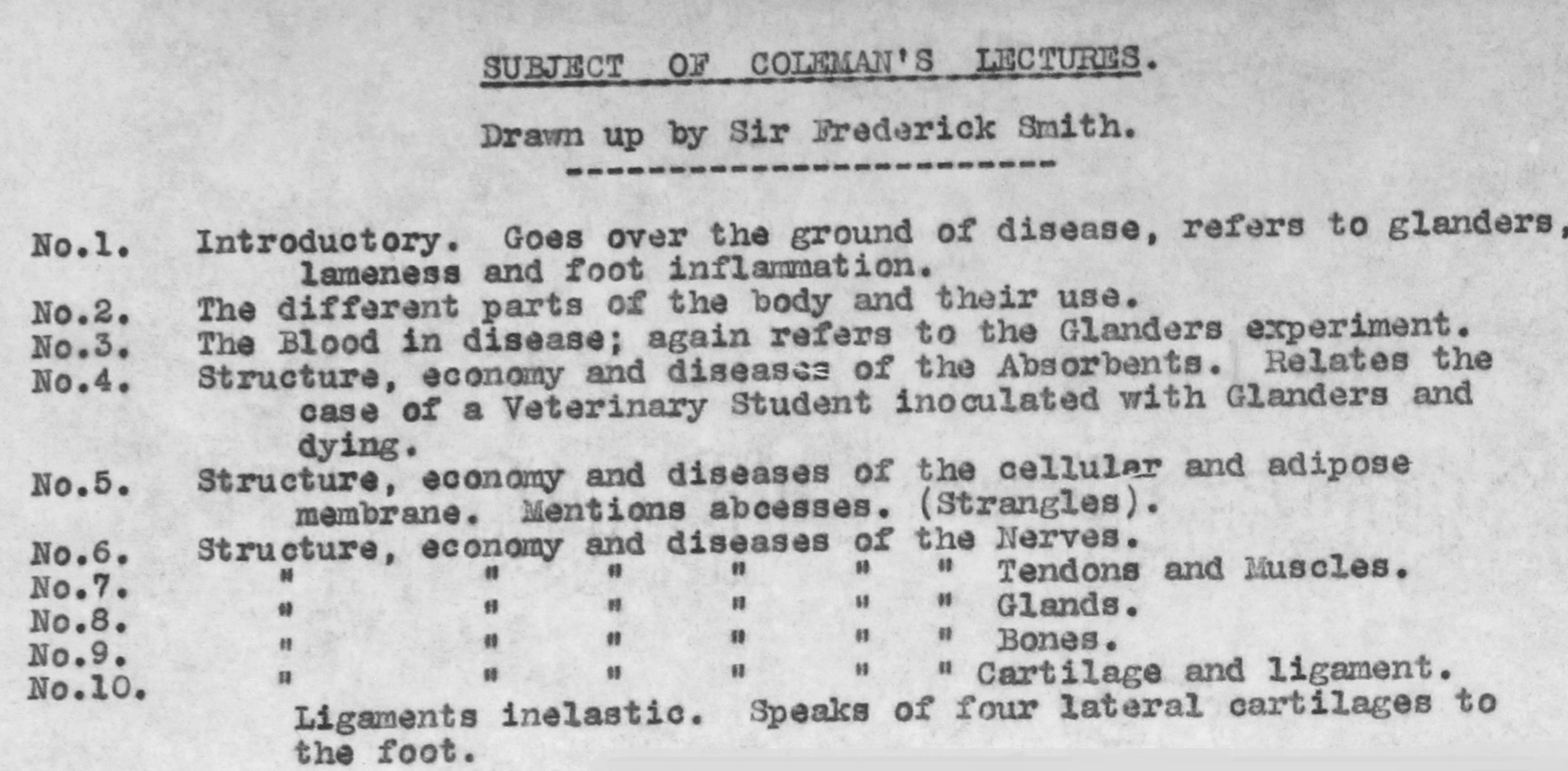

Alison Skipper, a vet and PhD student researching the history of health and disease in pedigree dog breeding, also employed extra-curricular wisdom in her transcribing – “my biggest leap of insight was in transcribing Thomas Brown’s letter, where I put my knowledge of Jane Austen and Georgette Heyer to good use in working out that D. Gds. meant Dragoon Guards!”

Far from being put off by the challenge of difficult handwriting, this was a big part of what Claire Coulthard enjoyed about the task – “transcribing the letters was similar to solving logic puzzles. When I completed a letter it gave me that same sense of satisfaction I get once I completed puzzles”. There was also the joy of new discoveries – finding what Claire called “little 1840 ‘isms’”, such as the more elaborate valedictions, no longer used in correspondence today.

And not all the writing was terrible! Carol Gray, a postdoctoral researcher at Liverpool University, told us that she fell in love with Belfast Vet William Taylor’s handwriting, and the correct and polite use of English across all the letters she transcribed.

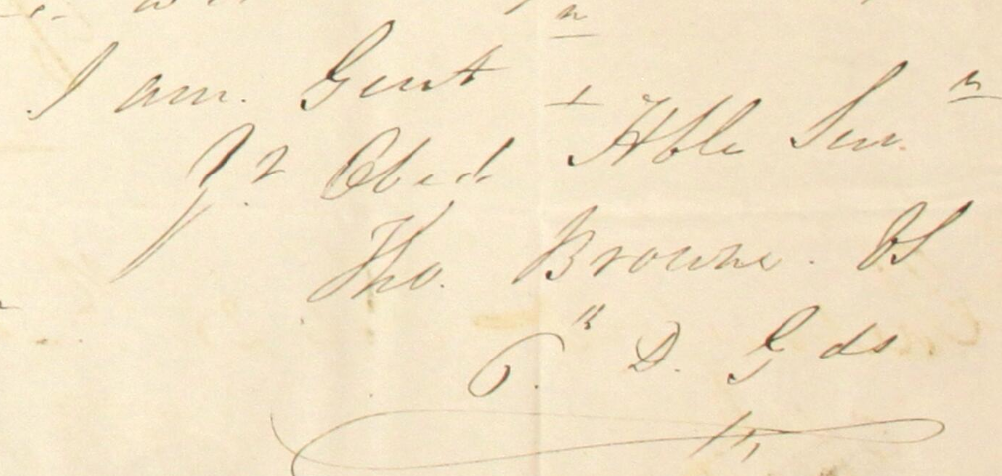

Letter from William Taylor, Belfast – probably the most beautiful writing in the collection!

Reflecting on the past

All the volunteers we spoke to found their experience reading these letters gave them insight into the way the profession in 1840 compares to today. For Carol Young, the “assumptions of class or gentility” seemed outdated, but she could remember “a time when we wore white coats, male vets were required to wear ties and female vets skirts, and vets were not supposed to be addressed by their Christian names!”

The main concerns of the vets in 1840, and their reasons for signing Mayer’s petition, continue to speak to the profession today. Ginny Kunch transcribed a letter from “a surgeon who indicated a concern that, in essence, the guy down the road was also claiming to provide veterinary services and, by god, what were the governors planning to do to address that particular issue! And I thought, well, that’s not unlike me now, as a practising veterinarian, trying to convince some clients that the local pet shop or human chiropractor is not an equivalent substitute for a properly qualified veterinary surgeon!”

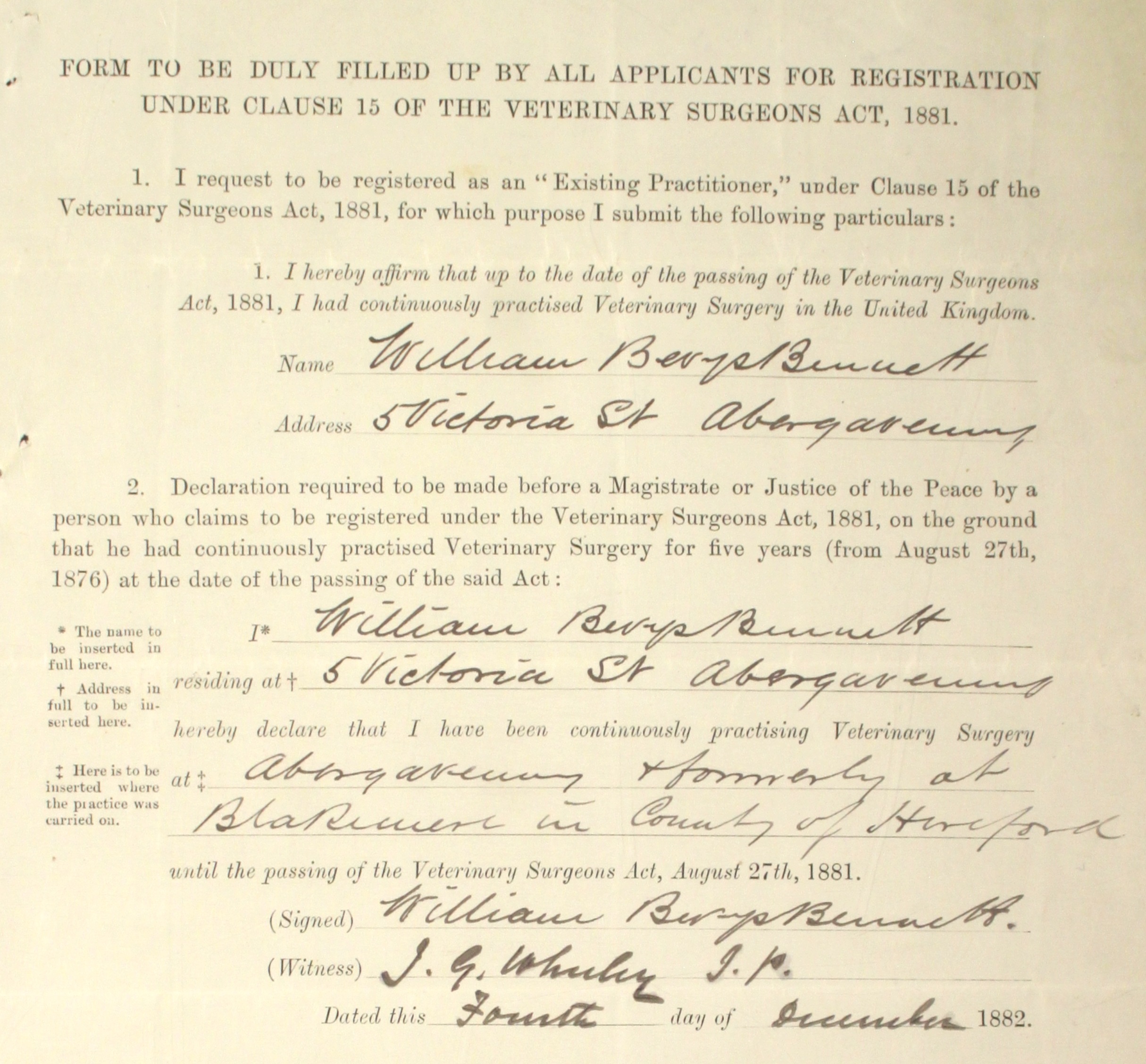

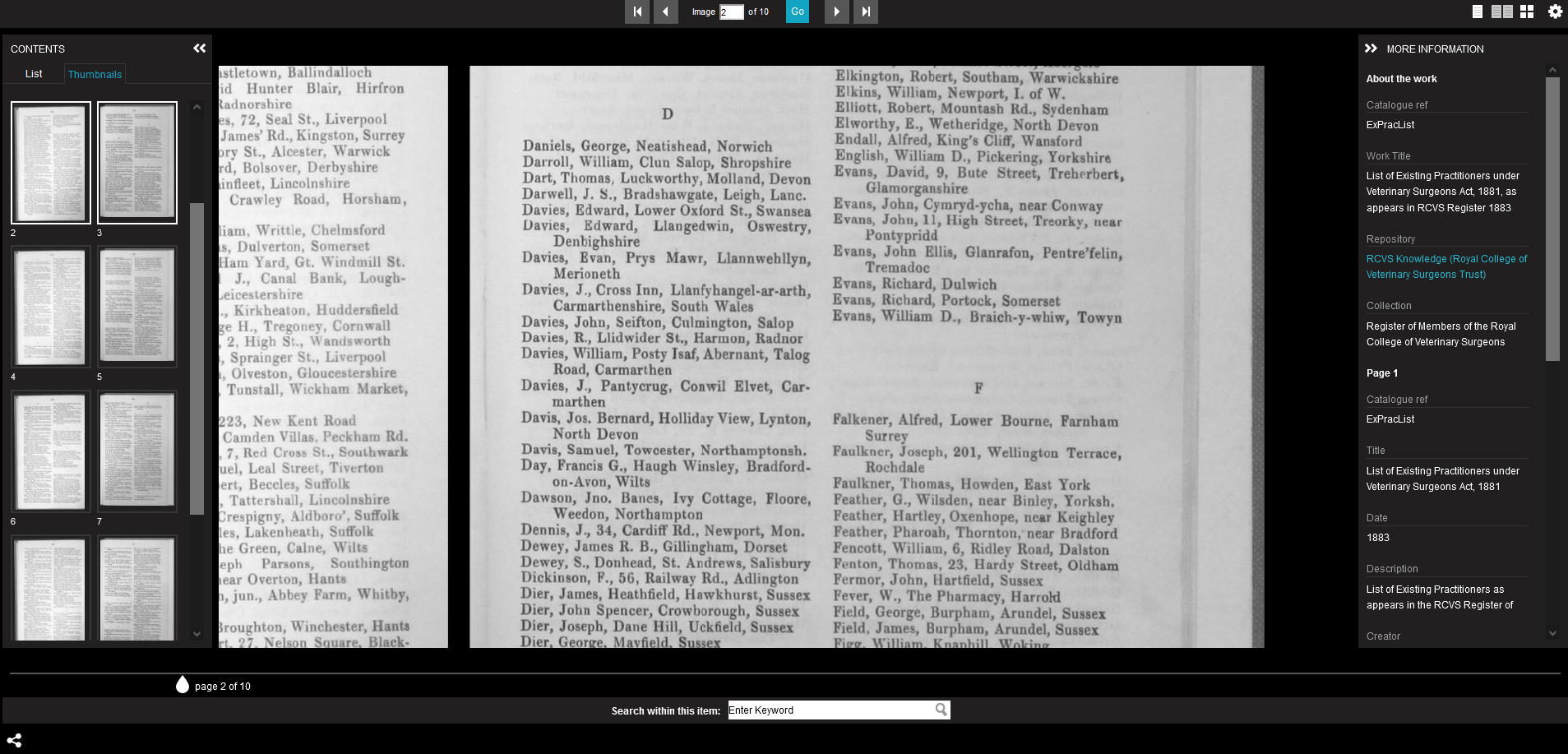

Carol Gray was interested in the drive for mandatory veterinary education and noted that “Although the profession is now well protected in terms of who can practise veterinary medicine, there are some parallels with the current drive to regulate veterinary paraprofessionals.”

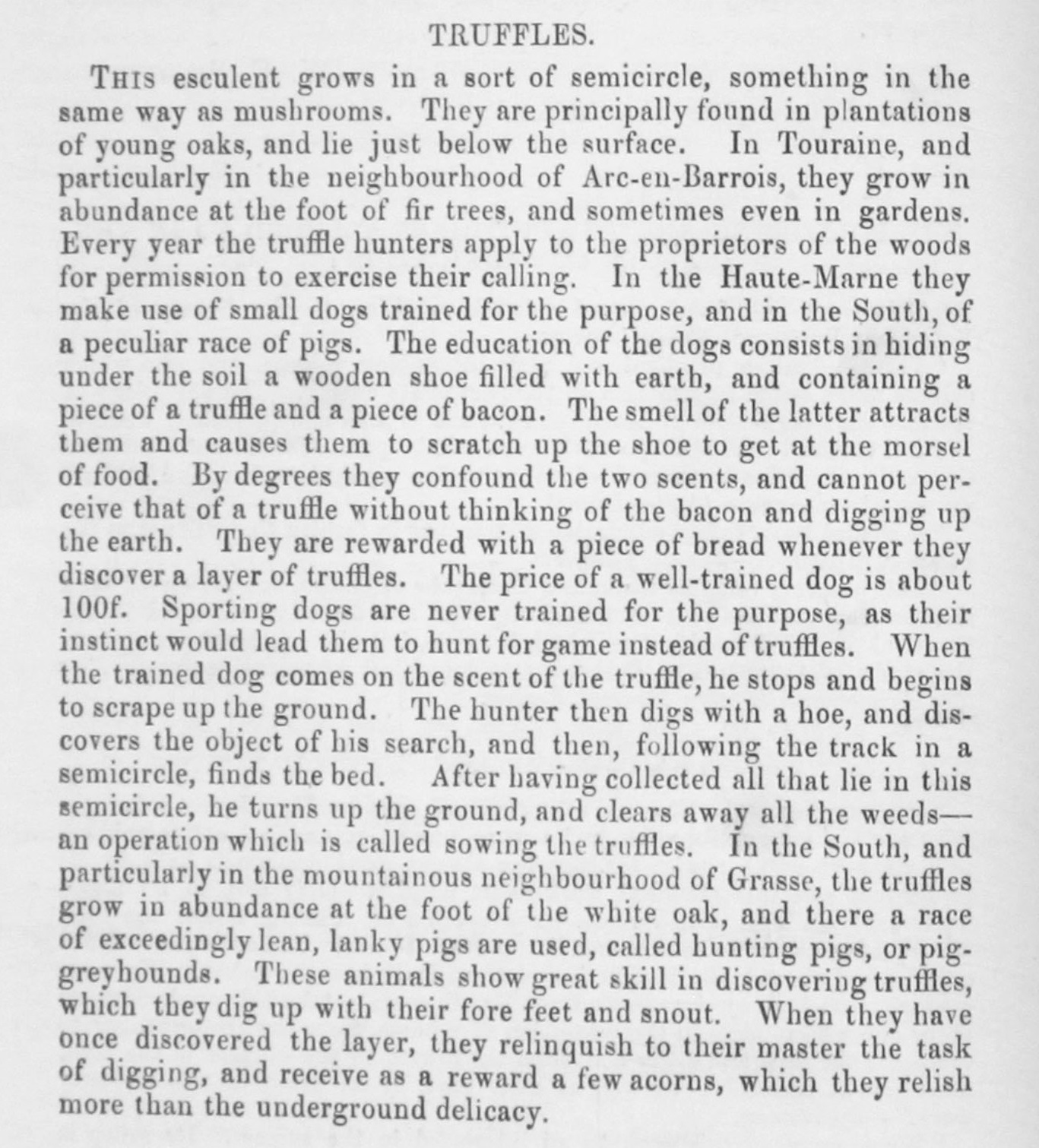

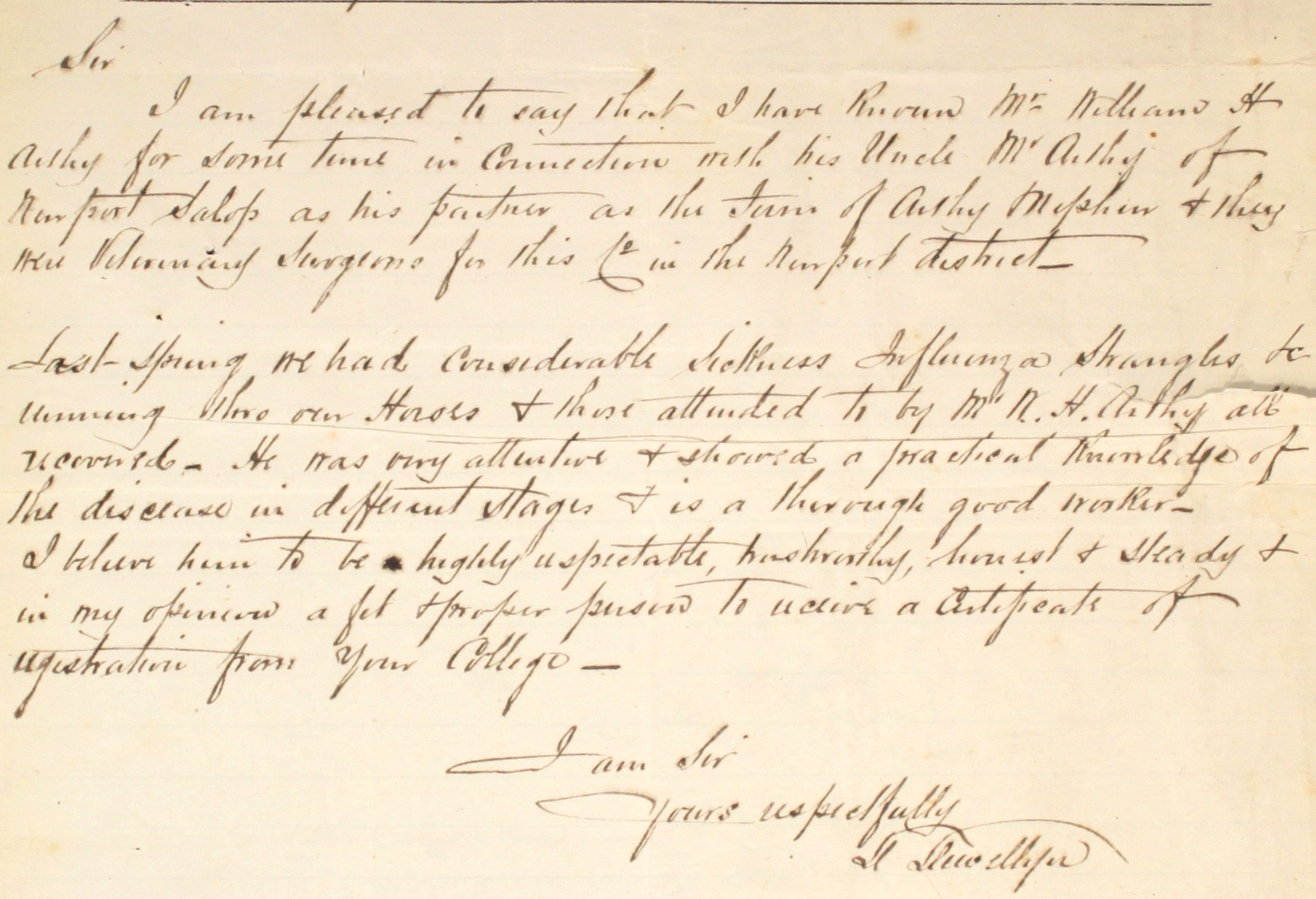

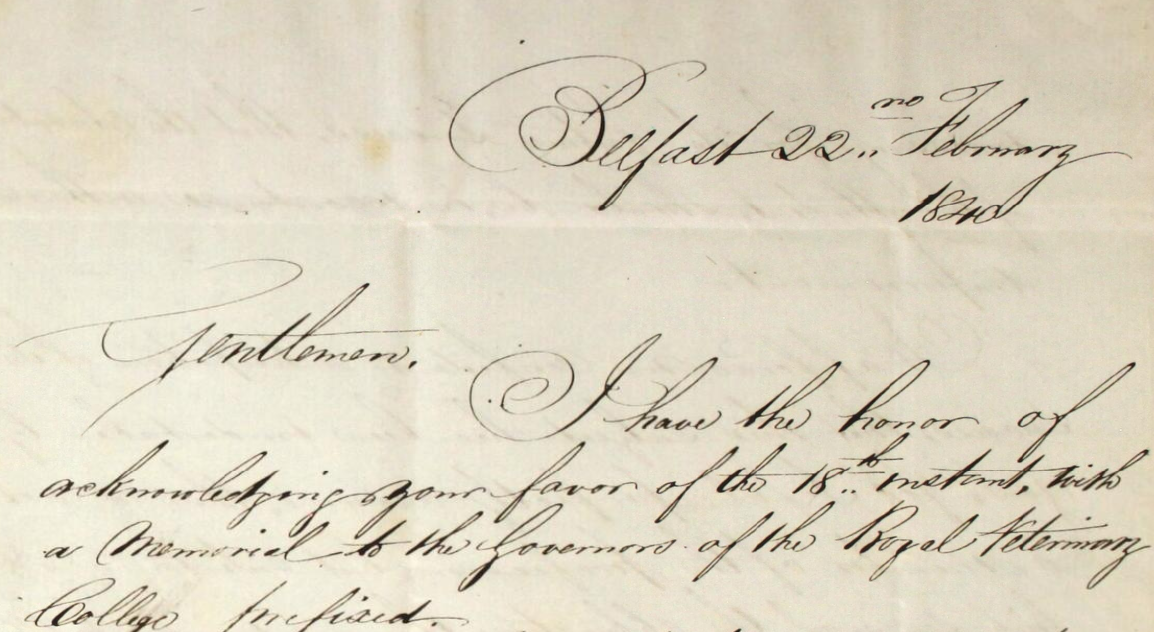

Letter from J Martin, Newbury, and accompanying transcription by Linda Lowseck

In a (very untidy) letter from J Martin of Newbury, Linda Lowseck identified mention of ‘Foot and Mouth Disease’, long before the disease was known by this name. For Linda, this was “yet another reminder of the gigantic increase in knowledge since 1840.”

The collection of letters as a whole is a fascinating snapshot of the early days of a now well-established profession, fighting for recognition. As Alison Skipper found, “there is a sense of fraternity and cooperation in these letters – a wide variety of veterinarians, scattered right across the country, coming together to support an important cause – which also reflects the best of our sense of community today.”

We are enormously grateful for the commitment and contribution of our band of volunteers on this project. Now that we have a talented pool of transcribers at our disposal, we are deciding which set of archives to set them upon next. Stay tuned to the blog for information about future projects.

You can browse the letters and their transcriptions on our Vet History Digital Collections site here.

–Lorna–