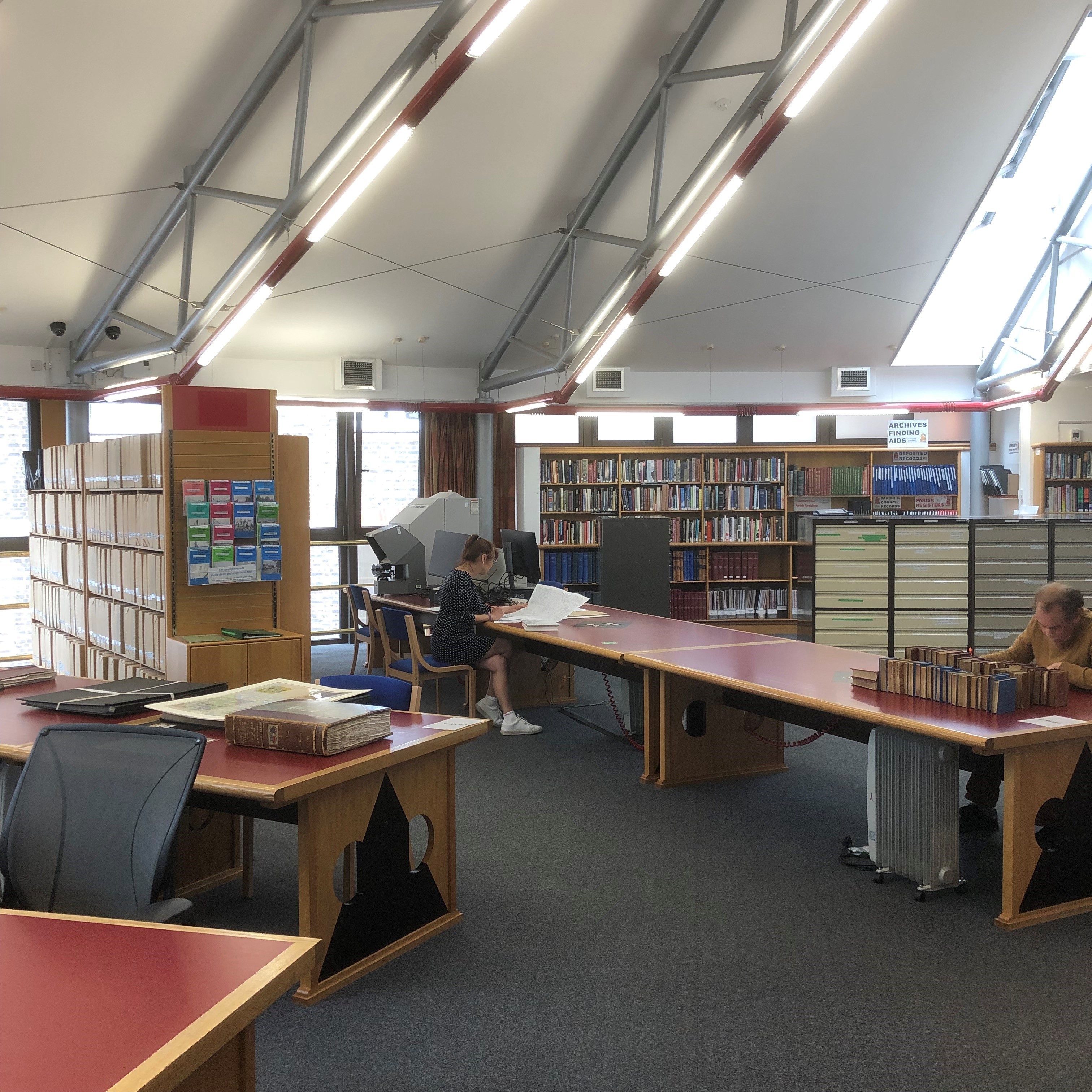

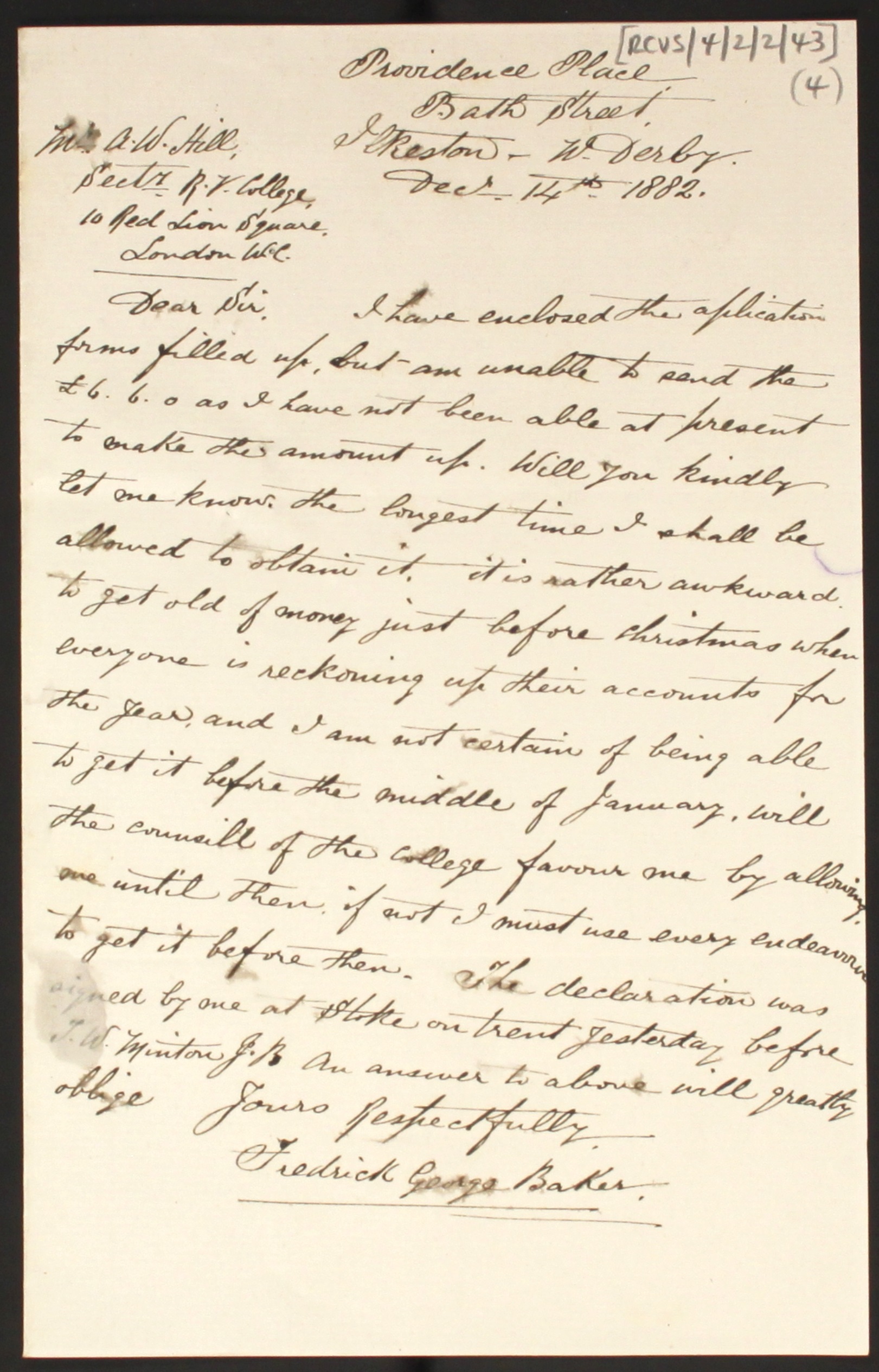

Screenshot of digitised and transcribed version of Coleman’s introductory lecture, on the Digital Collections website

Two hundred years ago today – which was a Monday not a Friday – students attended the Introductory Lecture of the 1821/1822 session at the London Veterinary College, now known as the Royal Veterinary College.

The lecture was delivered by Edward Coleman, Professor of the College, and thanks to notes of the lecture taken by student Edmund Gabriel, we can know exactly what he taught.

Gabriel’s notes from this lecture, and over 70 others, are held in our collections and are now being digitised, transcribed, and made available to all via our Digital Collections.

Plaster bust of Edward Coleman, on display in the Members’ Room at the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons

The teacher

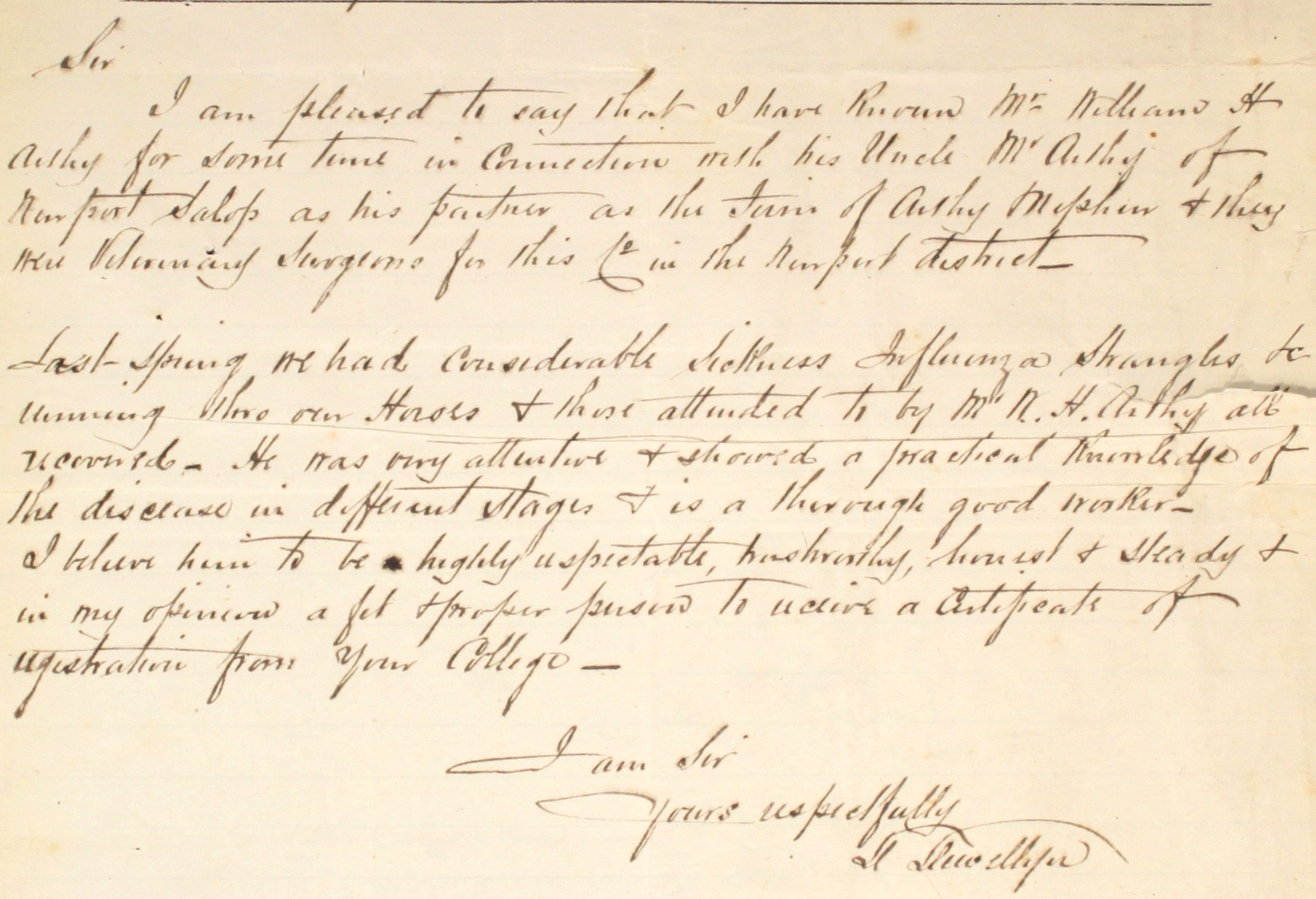

Edward Coleman (1766-1839) was a medical surgeon, with no veterinary training, who became head of the veterinary school in 1794, and Principal Veterinary Surgeon to the Army in 1796. He held both posts until his death in 1839. After the sudden death of the College’s first Professor, Charles Vial de St Bel, in 1793, Edward Coleman and William Moorcroft were jointly appointed to rescue the fledgling institution, which was mired in financial difficulties. Moorcroft resigned after only a few weeks, possibly due to a desire to focus on his private practice, or due to conflict with Coleman.

Reports of Coleman describe him as ‘mercurial’, but an intelligent man, and a gifted teacher. However, Frederick Smith, one of his severest critics, complained that his lack of veterinary experience, and fierce resistance to change, impeded the progress of the veterinary profession for decades. What is certain is that Coleman dominated the veterinary sphere in Britain for over 40 years, and greatly contributed to the growth of the profession in the early 19th century. Growth that would eventually lead to its reform and the creation of the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons.

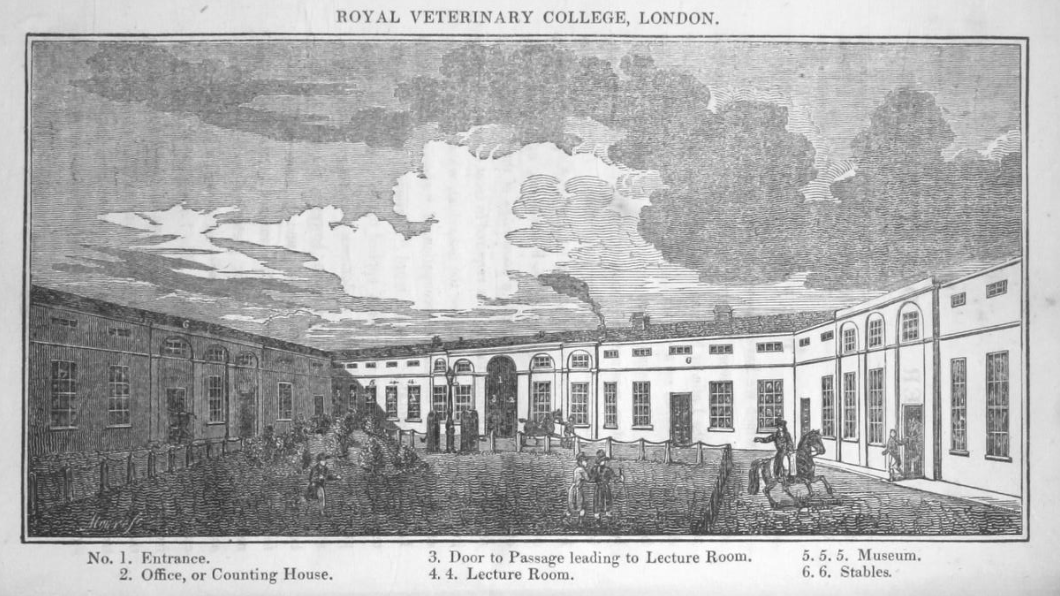

Engraving of the Royal Veterinary College, published in The Farrier and Naturalist journal, January 1828

The course

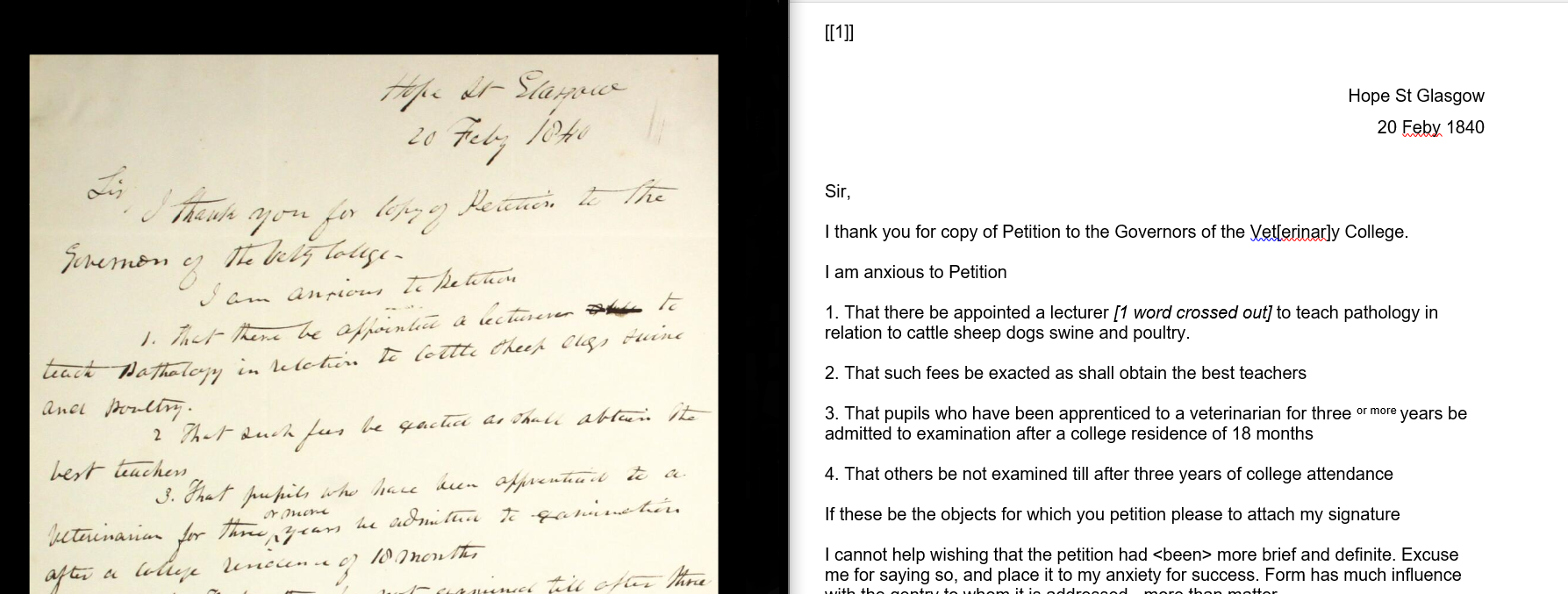

St Bel’s original plan for the College was a 3-year course, for boarding students, with an admission fee of 20 guineas (equivalent to around £1700 today). During Coleman’s time, the course length was eventually reduced to as little as 3 to 4 months, with the expectation that students would also attend lectures on comparative anatomy and pathology at medical schools.

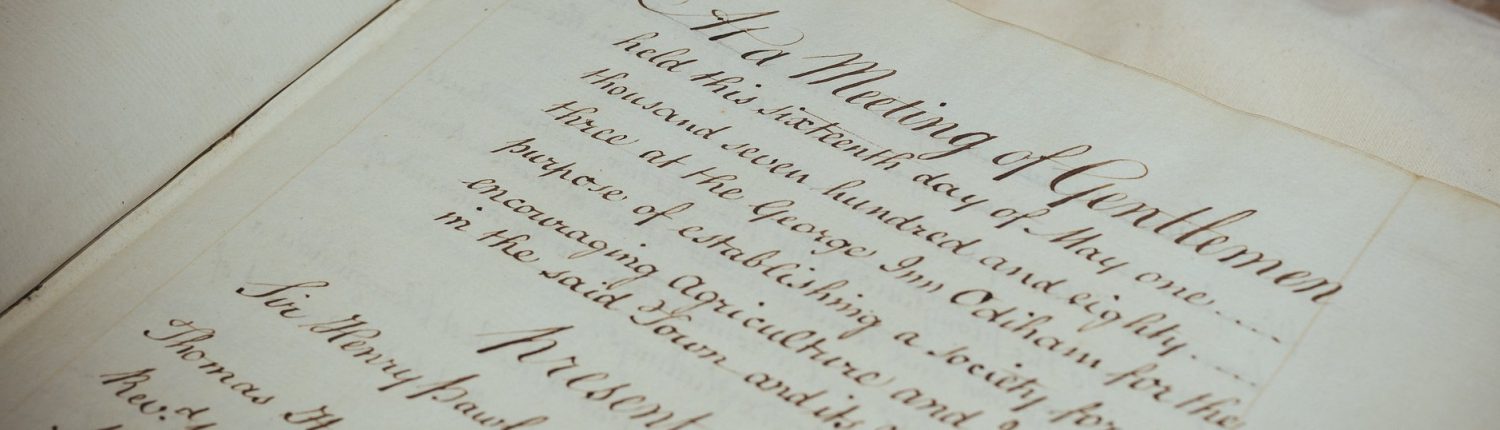

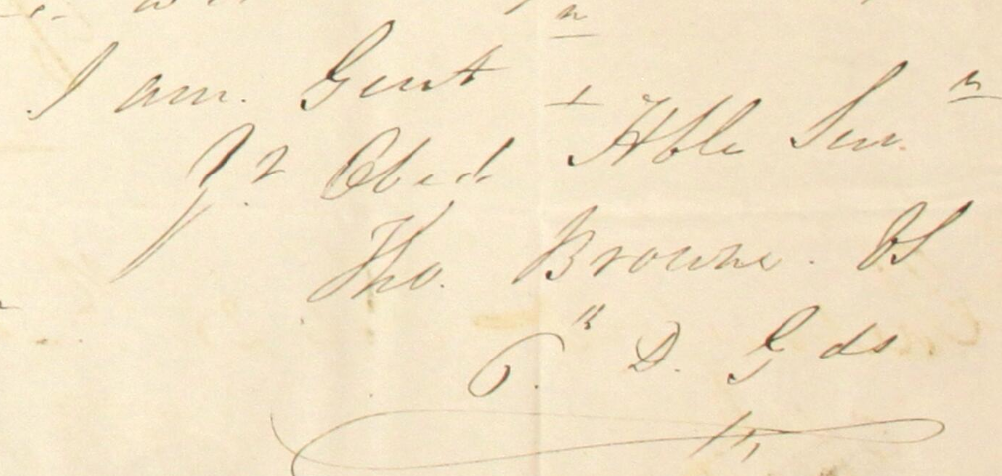

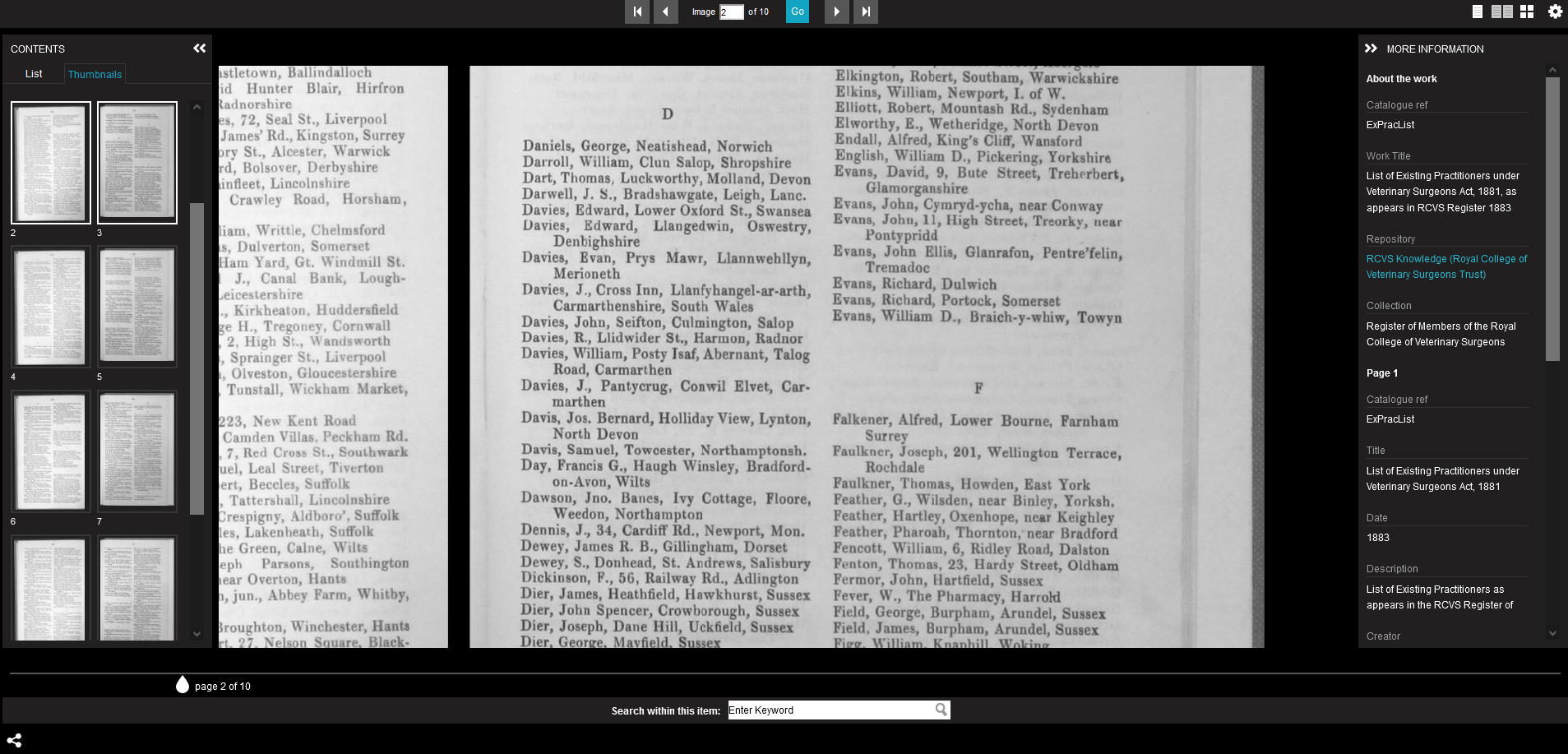

Students could then attend a viva voce examination by a board of prominent medical men, held quarterly at the Freemason’s Tavern. We know of at least 15 men who passed their examination in 1822, including Edmund Gabriel, the scribe of this collection of lecture notes.

Portrait of Edmund Gabriel, donated to the RCVS in 1883

The student

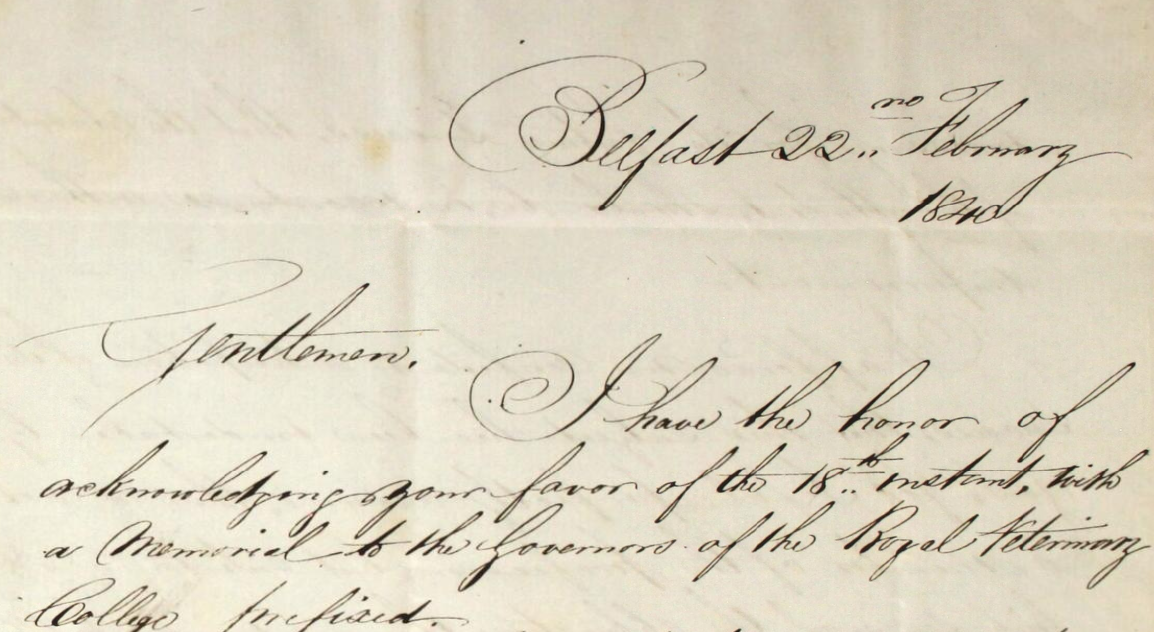

After graduating, Edmund Gabriel (1800-1864), seems to have remained in London, with his address listed as Fetter Lane, off Fleet Street. Later, in 1844, he became the first Secretary of the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons, where his distinctive sloping handwriting can be seen in the first book of Minutes of the Council.

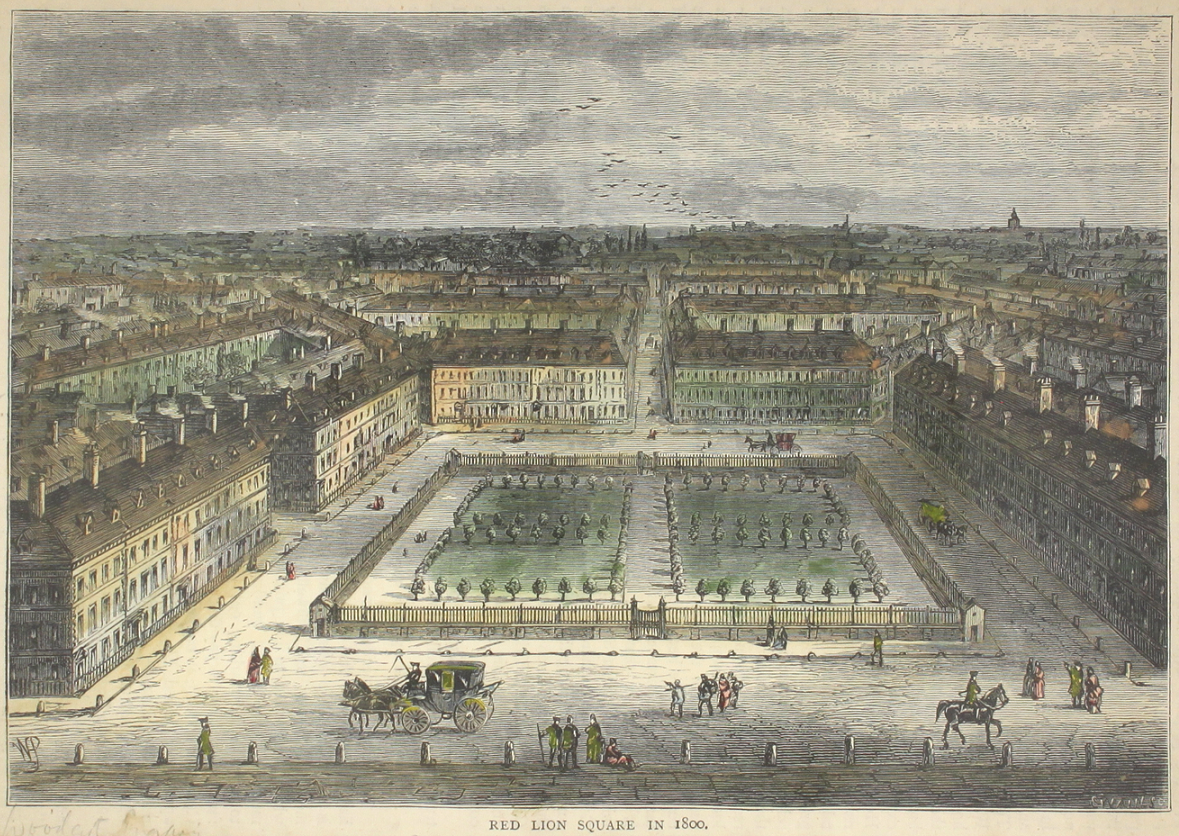

When the RCVS first moved into 10 Red Lion Square in 1853, Gabriel resided there for a portion of his annual honorarium. In 1856, he was elected veterinary surgeon for the RSPCA. He remained Secretary until ill-health forced his resignation in 1861, and died in 1864. His obituary in The Veterinarian describes him as “active and energetic in mind, gentlemanly in his demeanour… and was respected most by those who knew him best.”

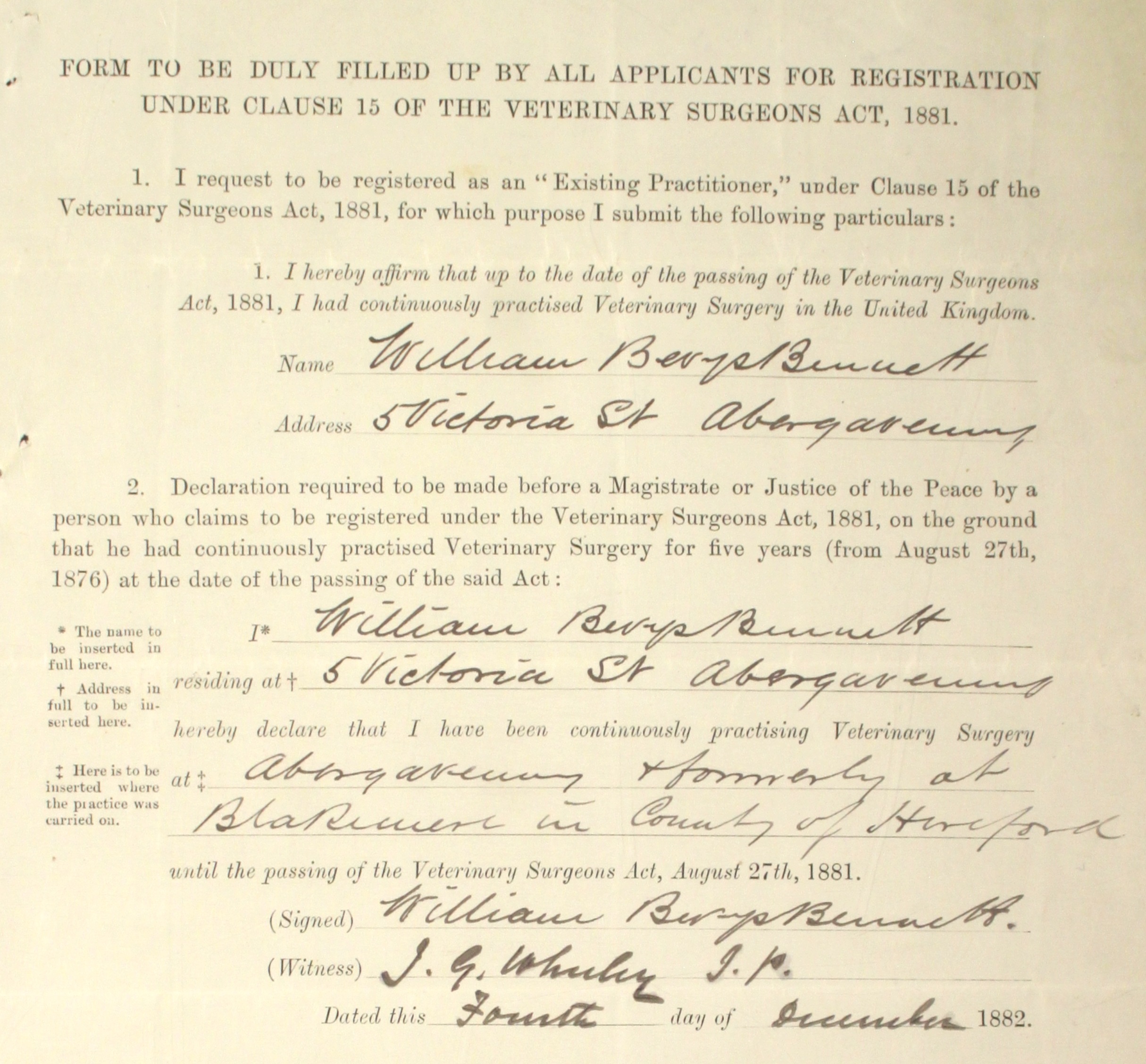

Screenshot of first page of Lecture 9 – Structure, ecomony and diseases of the bones.

The lectures

Gabriel’s notes comprise of 77 lectures, delivered from the 12th November 1821 to 19th June 1822. They almost completely relate to horses only, with the occasional mention of other species as a point of comparison. Most comparisons are made between equine and human anatomy and pathology, which is perhaps unsurprising, due to Coleman’s medical background, and the assumed medical experience of many of the students.

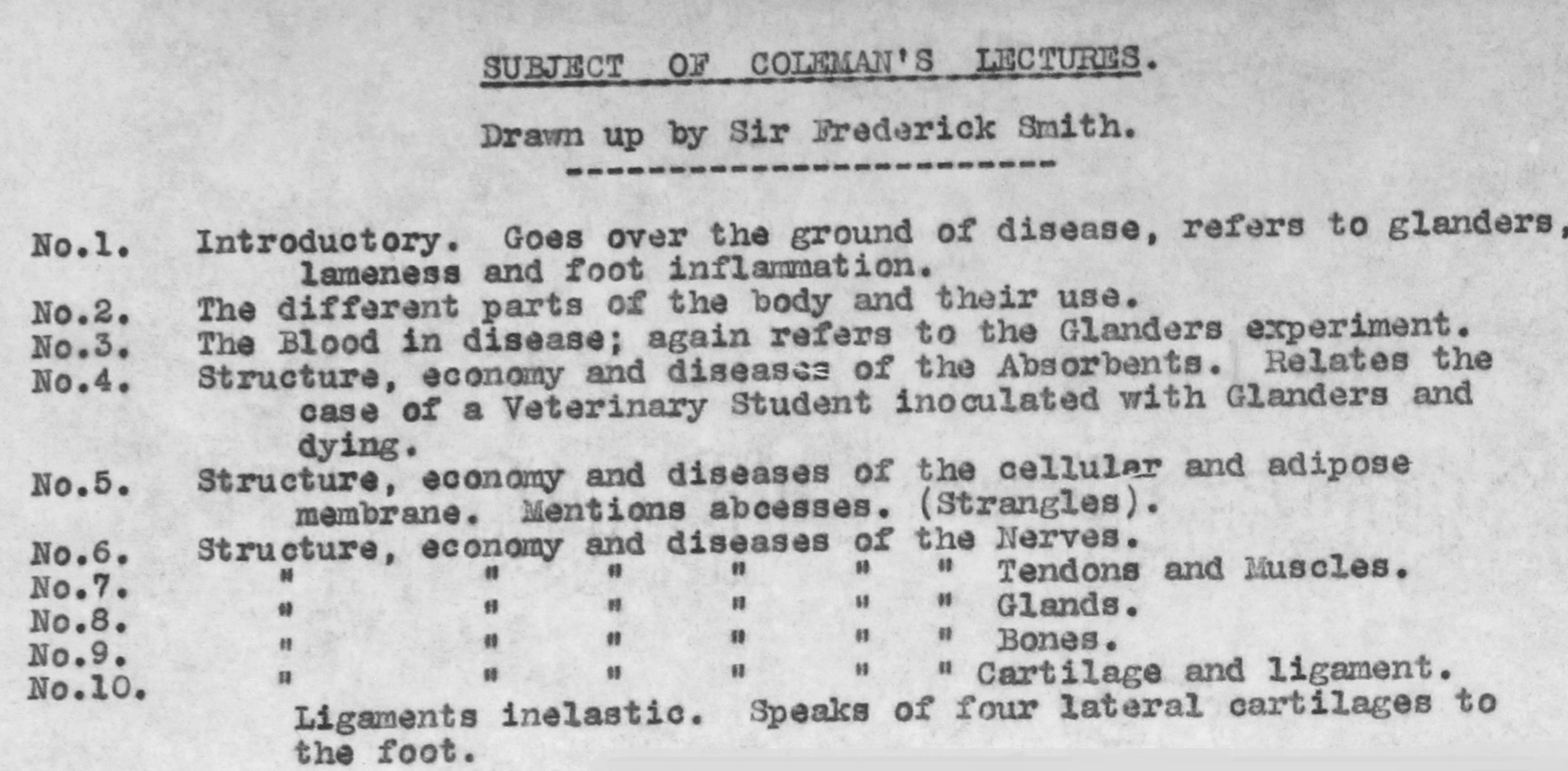

Extract from Frederick Smith’s list of subjects of Coleman’s Lectures

The lectures provide a fascinating snapshot of veterinary education, and general scientific knowledge, at the time. This was 10 years before Darwin sailed on HMS Beagle, and before the term ‘scientist’ was coined by William Whewell. Coleman taught that everything that happened in the body was for a purpose, even if that purpose could not yet be observed. The lectures include frequent mentions of trials and experiments carried out and the conclusions that are drawn from the results. For example, in Lecture 3, which relates to blood, Coleman speculates as to the cause of coagulation. At this stage, science is aware of red blood cells, but this was still the early days of microscopy, and it would not be possible to view platelets until higher-resolution microscopes were developed several years later. Similarly, in Lecture 4, Coleman says of glands:

“We know but little of their functions but those must be either something added or abstracted, we cannot suppose they should enter them for nothing, why do they go through them at all unless for some particular purpose”

The discovery of hormones and a wider understanding of endocrinology would arrive several decades in the future.

The transcriptions

As well as digitising all these lectures to add to the Digital Collections, we have begun the lengthy process of fully transcribing the text to make them even more accessible. Several volunteers who contributed to last year’s transcription project have gamely agreed to tackle Gabriel’s handwriting and lend their experience and veterinary expertise to help decipher more obscure anatomical terms that are a mystery to me!

Twenty of the lectures are uploaded already, and so far, five of them have transcriptions available. More will be added in the coming months – so watch this space!

-Lorna-