Honouring our ‘professional brethren on the Continent’

Nominations are currently been sought for RCVS Honorary Fellowship or Honorary Associateship.

These prestigious honours have a long history. The RCVS has had the power to bestow them since the Supplemental Charter of 1876, with the first Honorary Associateships made in 1880.

The minutes of the Council meeting of 29 July record President George Fleming’s opening remarks in which he gives an account of his attendance at an International Veterinary Conference in Brussels. He had been invited to attend in a private capacity and remarked that “the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons was not known on the Continent, and was not in any way recognised”. He thought that the “time had come when they should elect some of their professional brethren on the Continent as Honorary Fellows of the Royal College.”

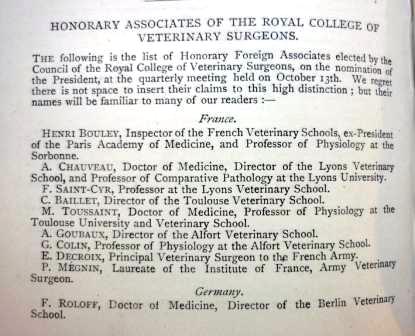

Closing the meeting, Fleming gives notice of a motion that he will bring to the next meeting: “he will bring forward the names of certain gentlemen… and move that they will be elected Honorary Fellows”. This he duly did at the Council meeting on 13 October of that year. Interestingly, the motion he actually laid proposed that the gentlemen be elected as Honorary Associates of the College and not Honorary Fellows.

So who was on the list of names? Well there was 67 of them – a fact that gave cause to some discussion in Council, with one member saying the President would “do better… to select some of the names” to which Fleming replied that they were all eminent and to select a few would have “appeared invidious.” Fleming might have had a point as the list includes the Professors or Directors of most of the European veterinary schools as well as several principal veterinary surgeons in the armies of Europe. I wonder if the attendance list of the Conference in Brussels was the basis for Fleming’s selection?

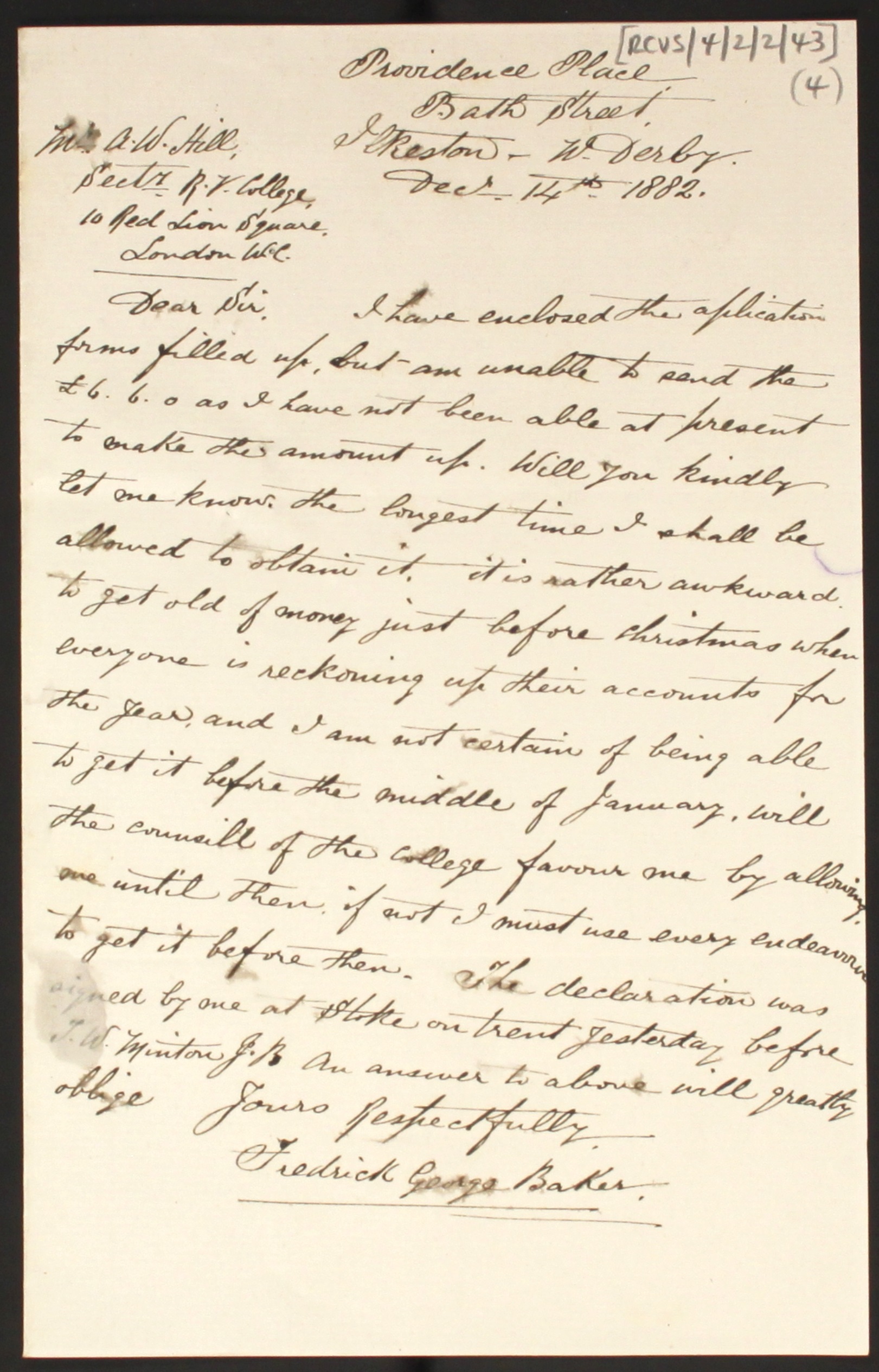

Following discussion about the cost of producing and posting out the certificates (which was to mirror the certificate for the RCVS Fellowship, including a Latin inscription) the motion was finally passed.

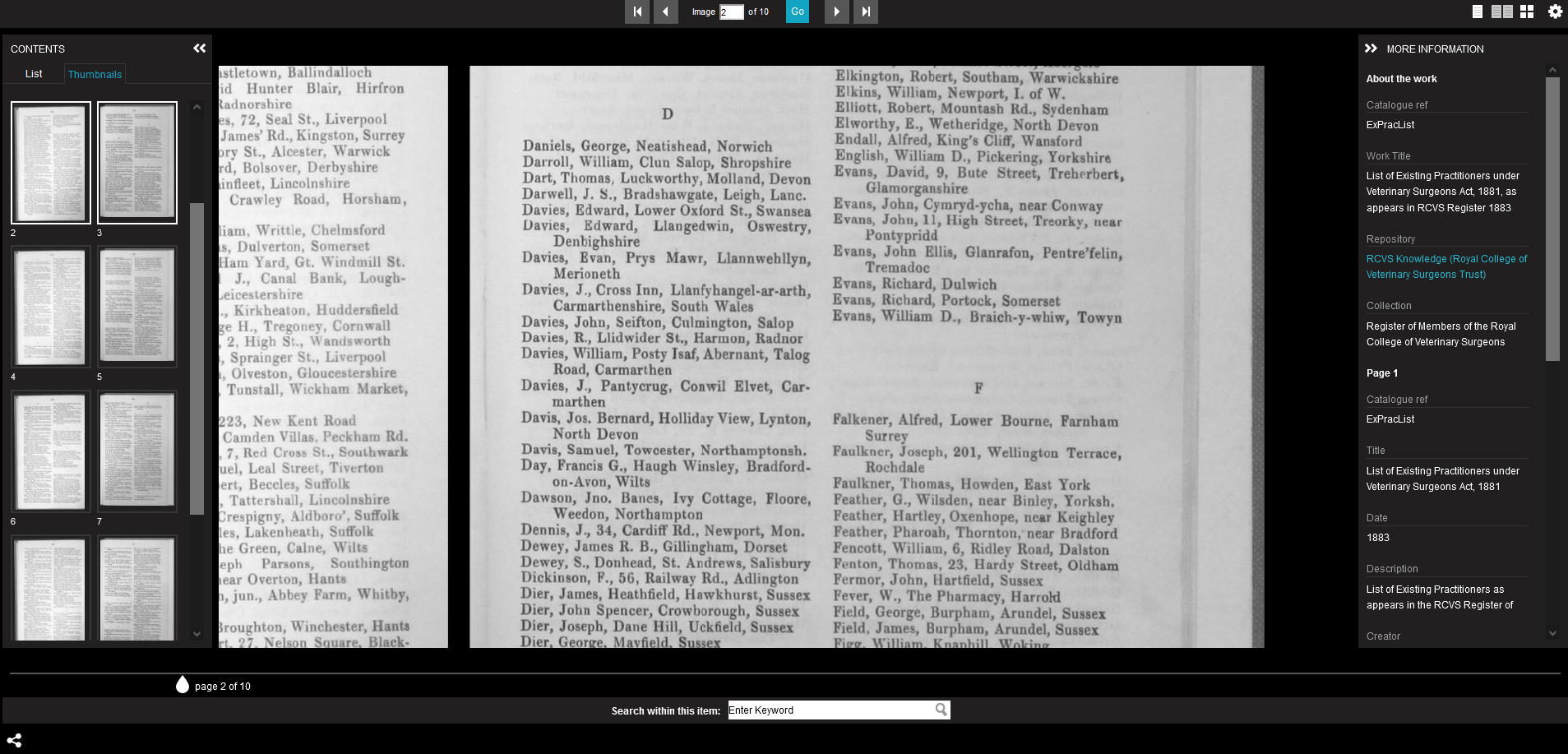

The full list of names was published in the Veterinary Journal and appeared in the RCVS Register of 1881 where they are named as Honorary Foreign Associates (the distinction between Honorary Associates (for UK-based individuals) and Honorary Foreign Associates was maintained until the late 1920s).

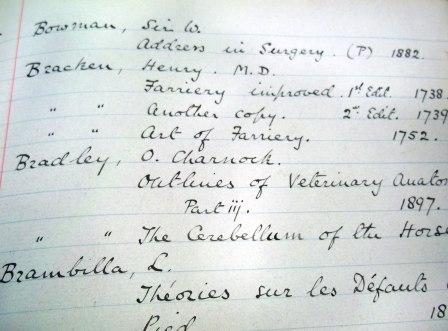

From a library perspective it is good to note that the ‘only’ privilege of being an Honorary Associate was free use of the library and museum (the privileges were modelled on those offered by the Royal College of Surgeons to their honorary members).

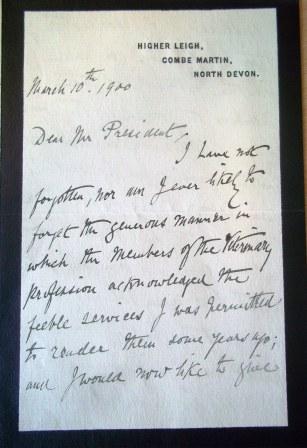

I’d like to think they appreciated this benefit – they certainly added to the collections as we have copies of books written by these gentleman in the Historical Collection – signed ‘with the compliments of the author’. I have often wondered what the connection was – now I know.