The National Air Raid Precautions for Animals Committee

Dog modelling a Spratt’s canine gas mask

The National Air Raid Precautions for Animals Committee (NARPAC) was formed in the Summer of 1939, one of a number of protection initiatives established by the Home Office at a time when war with Hitler’s Germany was becoming inevitable. The Committee was composed of representatives from the Home Office, the Ministry of Agriculture, the police, the veterinary profession, and animal welfare societies. Its aim was to create a strategy for the management of pets, livestock and working animals during war time, and to disseminate information and initiatives to the public. It did not get off to the best of starts.

NARPAC initially produced the pamphlet Advice to Animal Owners which suggested rehoming animals in the country, in a manner similar to the evacuation of children from towns and cities into rural locations. Alternatively, it suggested “If you cannot place them in the care of neighbours, it really is kindest to have them destroyed.” In addition to the widely distributed pamphlet, this advice also appeared in many national newspapers. It’s thought that within a week of the outbreak of war on 3 September 1939 between 400,000 and 750,000 pets were killed. Veterinary surgeries faced a deluge of requests from owners to have their animals put to sleep. One Home Office publication featured a prominent advert for a Captive Bolt Pistol which was, it claimed, “The standard instrument for the humane destruction of domestic animals.”

This horrific number of animal deaths must be viewed within the context of a period of escalating insecurity. During these terrifying, uncertain days many owners must have feared their pets would be killed or injured by bomb blast, as well as concern as to how to feed their animals if food became scarce. The tone of the pamphlet must have made many consider it their patriotic duty to have their animals destroyed.

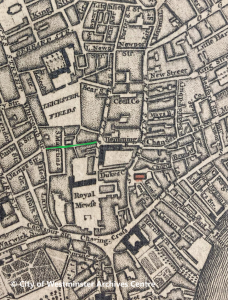

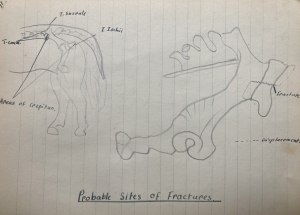

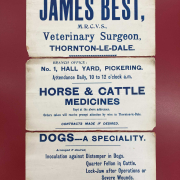

Nevertheless, something had to be done to stop these drastic actions. In October 1939 the Labour MP Herbert Morrison was appointed Minister for Home Security as part of the Wartime Coalition Government. He requested that NARPAC create new measures to reassure the public and to stop the animal slaughter. The result was a new focus on community-based activities in line with other Air Raid Precaution measures. NARPAC’s plan centred on three new initiatives. Firstly, the creation of a network of first-aid veterinary posts across the UK to return the focus on treating injured animals, not destroying them. As well as existing veterinary surgeries, dispensaries and animal shelters, it was hoped more posts would be created utilising empty shops or housed within larger shops. These posts were also intended to be mobile, able to go out into the streets or people’s homes to treat injured animals. NARPAC worked to ensure all posts were suitably resourced with equipment and staff, many of whom would be volunteers.

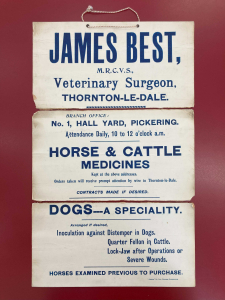

NARPAC Logo, from a registration leaflet

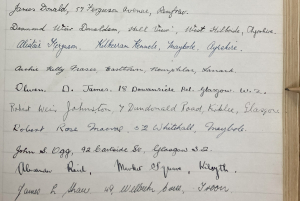

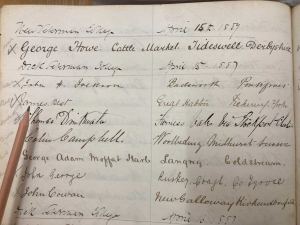

Secondly, NARPAC created a registration scheme for pets, livestock and working animals. By registering their animals, owners would be provided with a registration disc to attach to the animal’s collar, containing a unique reference number and the owner’s contact details. This meant that animal lost during air raids could be identified and reunited with their owner. There was also a specific appeal to horse owners, given that a distressed horse could bolt for miles and could cause danger for itself and others.

Thirdly, NARPAC created the post of National Animal Guards, staffed by volunteers from the local community. These Guards would be responsible for overseeing the registration scheme in their area, with each guard assigned responsibility for around one hundred households. As an initial step the Guards were to go door to door encouraging registration and distributing discs. Guards were also given a collection tin for donations, including from those households without animals. Beyond this Guards were to aid animal owners in finding their nearest veterinary post but were not expected to perform any treatment on animals. Guards could be recognised by their white armbands with the NARPAC logo and would also have a notice outside their homes. This was therefore an important, visible role within the community similar to that of the ARP Wardens who activated air raid warning sirens and ensured blackout conditions were observed. As with Wardens, NARPAC Guards had permission to be on the streets during air raids, either on foot or in their vehicles provided it displayed the NARPAC logo. As the NARPAC leaflet stated, “The National Animal Guards are the FRIENDS of your animals – when they call, treat them as friends”. It was suggested that Guards should aim to call at each house every six months to check up on registration and hopefully collect more donations.

Guards were organised by a locally appointed Honorary District Organiser (“…some suitable person, who may be agreed upon…”) who would initially divide their area into a number of divisions. Each division would also appoint Chief Animal Guards, responsible for the recruitment and management of the National Animal Guards. The Chief Animal Guard was also responsible for depositing donations into specially created bank accounts.

Many animal welfare organisations became involved with NARPAC including the RSPCA, the PDSA, the National Farmers’ Union and the National Canine Defence League. The RCVS was invited to nominate a suitable member for NARPAC’s Board of Control. One of the RCVS’s former presidents, GH Livesey was duly selected for the post. George Herbert Livesey had graduated from Edinburgh as a veterinary in 1899 and set up practice in Hove, Sussex where he remained until he retired in 1924. He was elected to the RCVS Council in 1922 and served on a number of boards including the finance committee, library committee (elected chair in 1928) and the animal charities committee. He served as President for the 1938/39 term and joined the War Emergency Executive Committee, from its establishment by a Council resolution dated the 27th of September 1939. Sadly, Livesey would not live to see the return of peacetime, dying on the 20th of November 1943. Such was his commitment to the veterinary profession that Livesey left money in his will to provide benefit to ‘…veterinary students and young practitioners in reduced circumstances to assist them in their studies.’

GH Livesey, committed Committee man

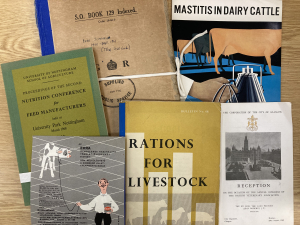

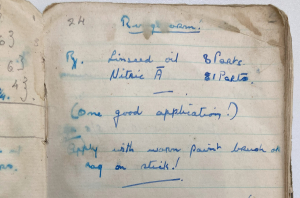

With new measures in place NARPAC created a new public information booklet entitled Wartime Aids for All Animal Owners to explain these new provisions. This booklet emphasises the public’s collective responsibility for caring for the nation’s pets and livestock, including the important advice that “Those who are staying at home should not have their animals destroyed.” Much of the booklet contains sensible, achievable guidance for owners of all sorts of animals. This includes recipes for feeding cats and dogs should food become scarce, plus advice on the availability of sedative medicine suitable for nervous animals. There’s advice on protecting cage birds and providing gas-proof accommodation for poultry. The booklet also recognises that with the rationing of petrol, horses were becoming more prevalent as a means of transporting goods and people. Accordingly new Horse Emergency Standings were to be created as temporary accommodation for horses during air raids. Many of these standings were in public parks, but more were in private stables or empty garages.

The booklet considers “There are no suitable gas masks for animals”. However, that was soon to change as manufacturers began creating new animal safety products. One example is the dogfood firm of Spratt’s of Poplar who extended their output to include wartime protection for dogs. Dog gas masks were produced in a range of sizes suitable for different breeds. Each pack included a training hood to help the dog become accustomed to wearing headgear. Spratt’s also produced white blackout coats to make dogs more visible at night, and a range of gas-proof kennels; a large wooden box with its own air filter system. According to newspaper adverts, the box’s solid walls would help deaden the noise of gunfire, plus a top window so owner and dog could see each other. These features, the manufacturers hoped, would be enough to reassure the dog once placed inside.

With hindsight it’s easy to say that NARPAC’s initial pamphlet should not have advocated destroying animals, even as a worst-case scenario at a time of national crisis. Something clearly had to be done at the outbreak of war, and the overwhelming response to these words could not necessarily have been predicted. Fortunately, the range of parties working under the NARPAC banner acted swiftly to produce workable measures focusing energies onto animal welfare, with the emphasis on community participation and collective responsibility.