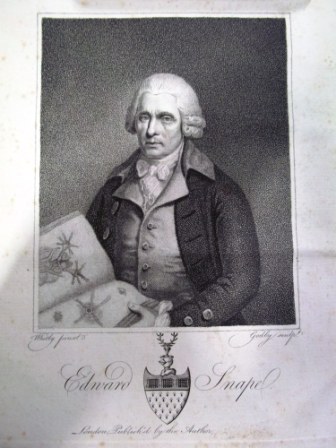

Edward Snape’s muscular preparation

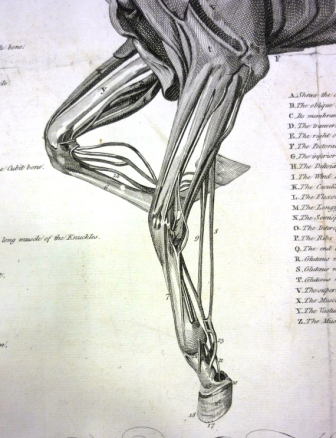

The library is currently having a makeover which has meant emptying shelves and cupboards. One thing that has come out of its cupboard is a print titled ‘A muscular preparation of a horse with references.’

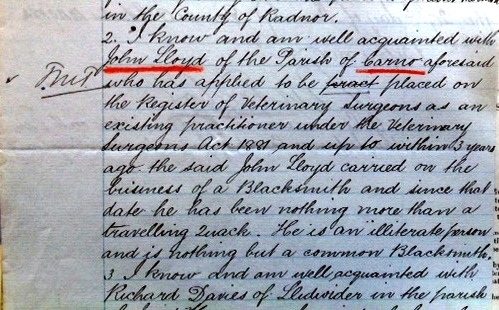

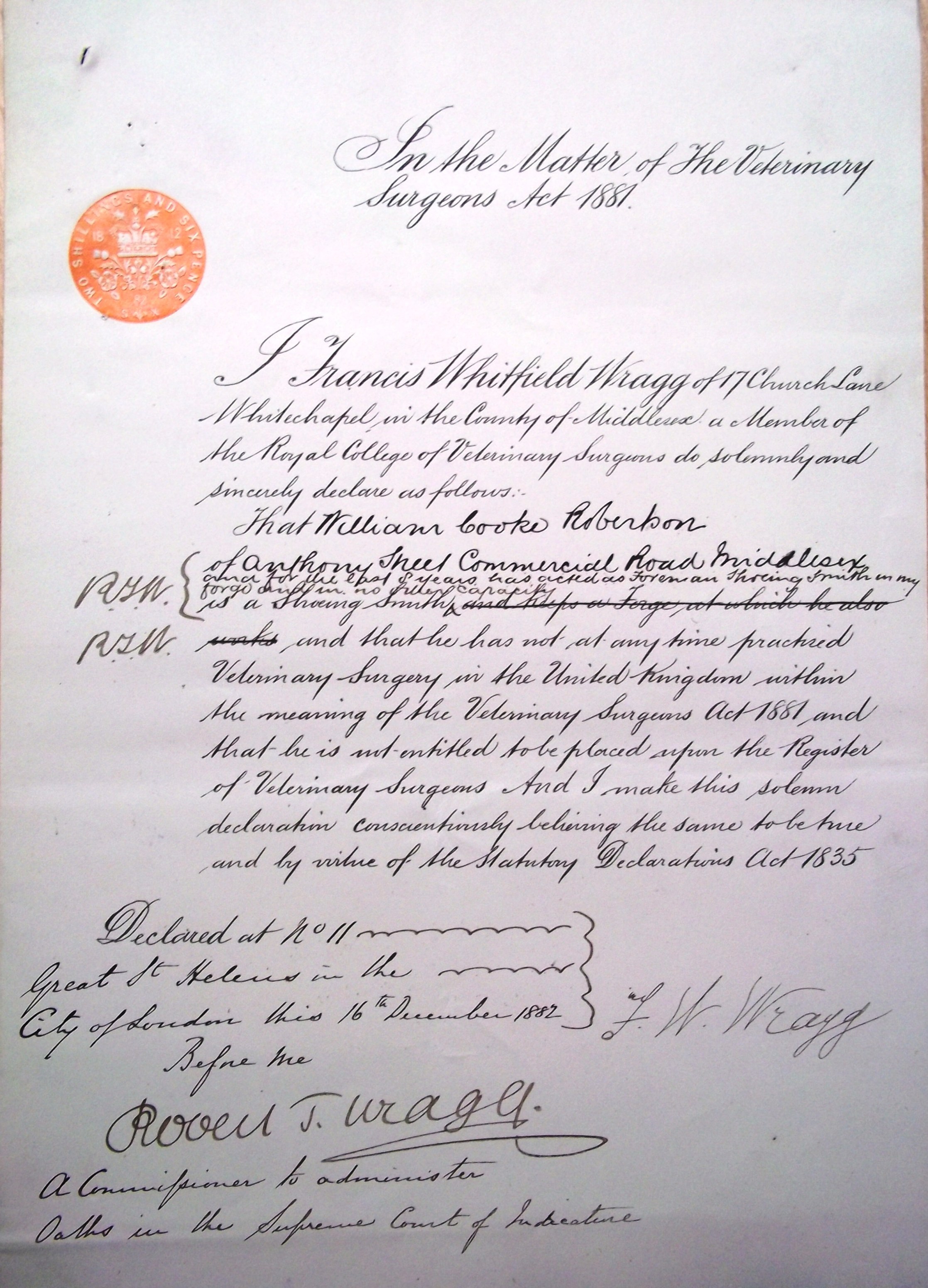

The inscription reads:

“To His most Excellent MAJESTY GEORGE III. King of Great Britain &c &c. This Plate is most humbly inscribed by His Majesty’s most faithfull (sic) Subject and Servant Edwd Snape Farrier to their Majesty’s & the 2nd Troop of the Horse Guards.

Published 15th April 1778 and sold by E. Snape in Berkeley Square”

Edward Snape 1728-18?? was a London based farrier who claimed to be a descendant of Andrew Snape of The Anatomy of an horse fame.

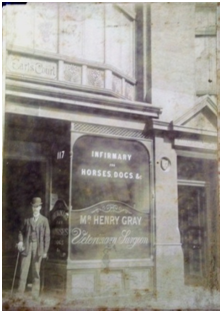

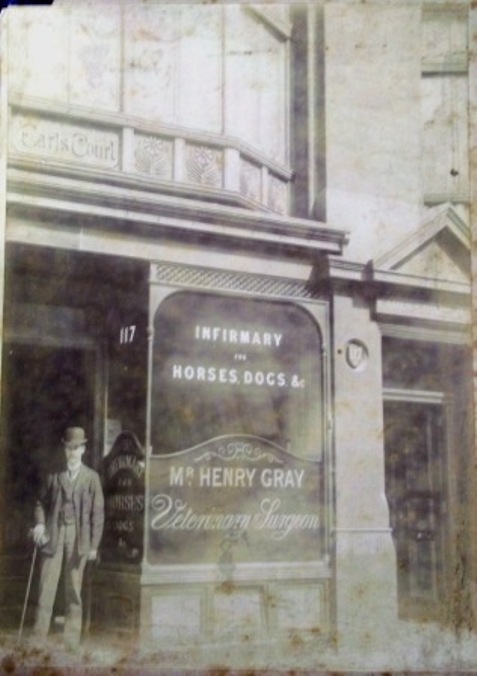

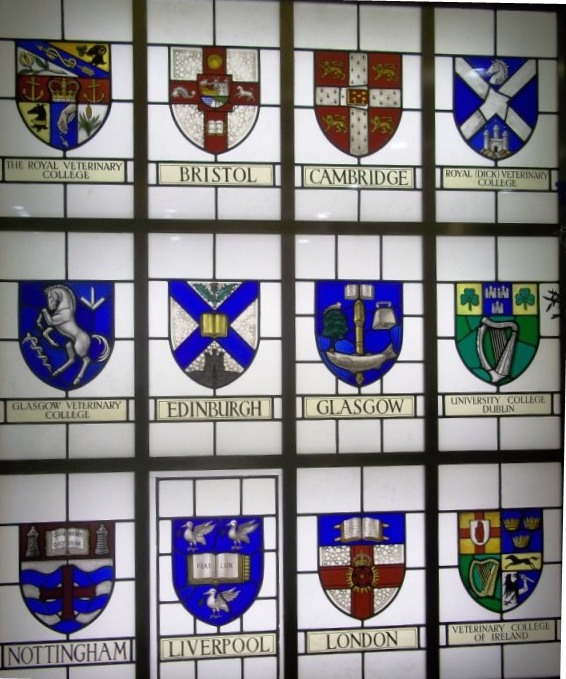

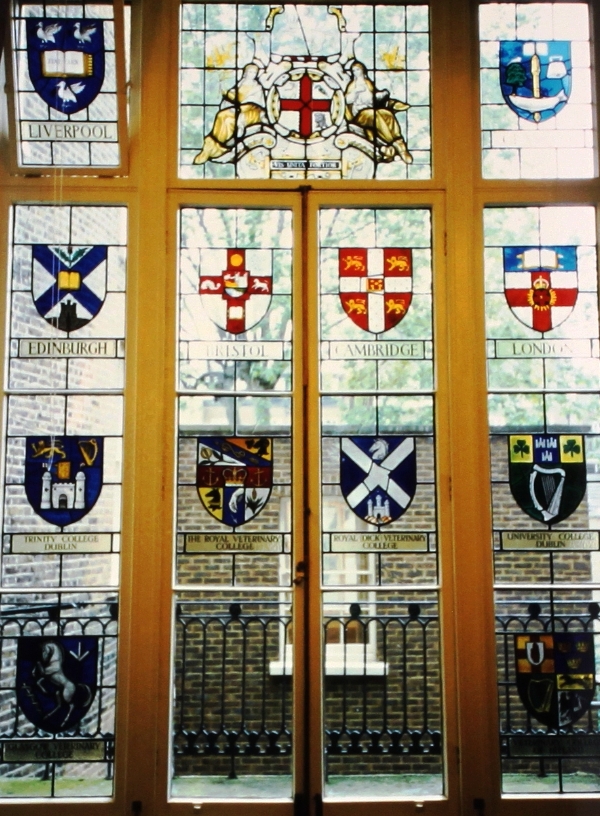

Little is known of him but he seems to have had a genuine desire to see his profession progress. In 1766 he proposed the establishment of a “hippiatric [horse] infirmary” as a school for the “instruction of pupils in the profession.” The school eventually came into existence in Knightsbridge in 1778.

There is a short account of the school in an ‘advertisement’ (which reads like an obituary though Snape was still alive and presumably the publisher knew this!) in the 2nd, 1805, edition of the Practical treatise on farriery (1st edition 1791) though it doesn’t actually say it opened – just that it was built. The ‘advertisement’ also makes the following claim “whatever benefit the Country now derives from the establishment of the Veterinary College, originated in him.”

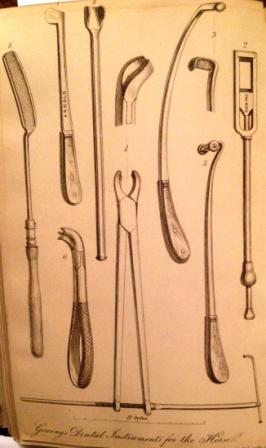

Alongside the Practical treatise the print is the only other thing that Snape is known to have published. My research suggests that Snape’s print is based on an earlier one by Jeremiah Bridges. Looking at reproductions of the two prints side by side in the Veterinary History article the illustrations are remarkably similar though Snape has added labels (his ‘with references’). If it is true that Snape has copied an existing illustration then he would share a trait in common with his supposed ancestor Andrew Snape who used Carlo Ruini’s Anatomia del Cavallo as the basis for his work (for more information on Ruini’s work and Andrew Snape)

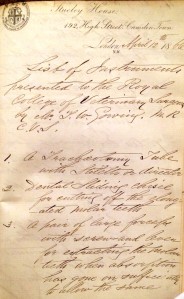

It would appear that the print I ‘found’ is not the first ‘edition’ as it has some minor changes to the inscription when compared to the earliest known copies. Luckily we also have a copy of the earlier printing (of which Wood says there are only 4 known copies)

One interesting thing about the early version of the print is that whilst it bears the date 1778 all the known copies are on paper bearing an 1808 watermark. I doubt we will ever know why that is the case. It could it be that it was prepared for use at the hippiatric infirmary but not actually printed until the later date. Or was it produced in 1808 but ‘back dated’ to give some credence to the claim that the benefits of the Veterinary College (now the Royal Veterinary College, founded 1791) originated in Snape?

Once the library is back in order I will give the two prints a proper outing and put them on display – do come and see them.

Update: See comments for further information on Snape

Bibliography

Smith, Frederick (1924) The Early history of veterinary literature and its British development Vol II. London: Bailliere, Tindall & Cox

Wood, John GP (2004) A tale of two prints: Jeremiah Bridges and Edward Snape Veterinary History Vol 12 no 2 pp 173-183