Changing times

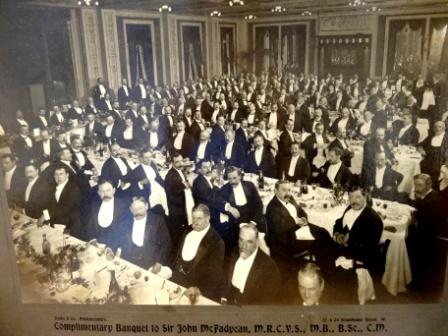

The editorial in the issue of The Veterinary Record published 100 years ago today was titled ‘Some changes in our profession’. In it the author links the noticeable decline in equine veterinary work to the development of ‘motor traction’ but also notes that:

“new channels of work are opening up to us in compensation…The two chief substitutes are canine and feline practice and preventive medicine.”

The editorial then describes the ‘immense’ expansion of work with dogs and cats in the last thirty years, how almost every practice now treats these animals and how the knowledge of canine and feline diseases and treatments has grown.

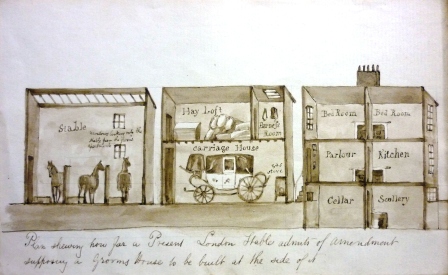

Looking at the statistics on horse ownership in the decade prior to 1912 we can see just how much impact the growth in motorised transportation had. In 1904 there was an estimated 145,000 horses in London, many of which were owned by the London General Omnibus Company for use in its fleet of horse drawn buses. By 1911 the LGOC was selling off horses at a rate of 100 a week and ran its last horse bus in September of that year.

Given that scale of change it was inevitable that veterinary surgeons had to look for other sources of income and the increase in the keeping of dogs, in particular, as companion animals offered one such opportunity. However the interest in the care of small animals began 50 or so years earlier and had been increasingly reflected in the literature from the mid 1800s.

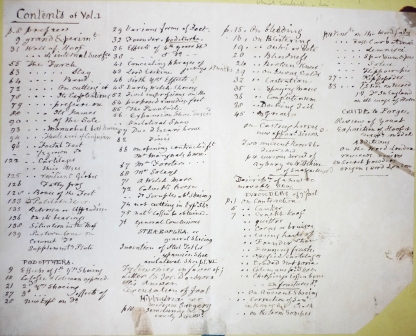

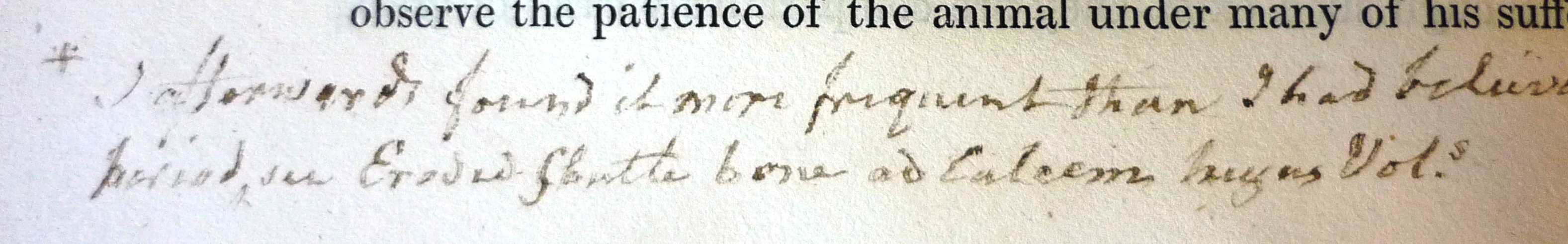

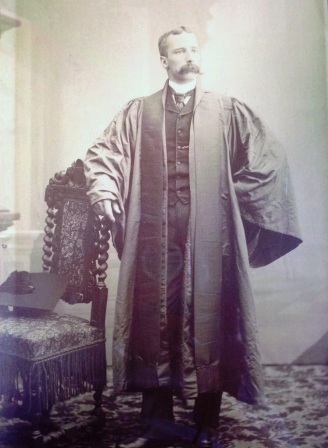

In 1847 Edward Mayhew wrote two articles in The Veterinarian relating to dogs and cats, then in the following year in an article he disclosed that canine work formed the bulk of his practice. His book Dogs: their management, published in 1854, could perhaps be seen as the start of a new focus for the profession.

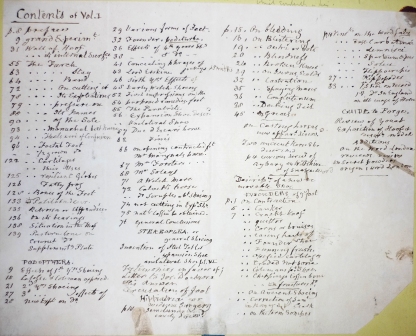

Further books followed eg John Woodroffe Hill’s The management and diseases of the dog (1878) and John Henry Steel’s A treatise on the diseases of the dog (1888). The first specific text on small animal surgery was Frederick Hobday’s Canine and feline surgery (1900).

These changes were also reflected in the subjects of theses submitted for the award of RCVS Fellowship – from 1893-1911 there were 5 theses on small animals topics, between 1912-1931 the number almost trebled.

Moving forward nearly a 100 years statistics in the 2010 RCVS Survey of the veterinary profession show that 72% of the time of veterinary surgeons working in clinical practice is spent working with small animals.

So the 1912 editorial was correct in its prediction that small animal practice would continue to increase and in its confident assertion that:

“we have become of real use to a section of the community very much larger than the horse-owning one and shall continue to be so.”