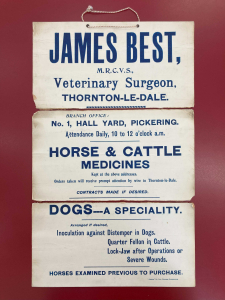

James Best’s Advertisement

Misdeeds contrary to the 1881 Veterinary Surgeons Act came in many forms, from employing unqualified people to the mis-certification of sick horses. Similarly, the idea of advertising was seen as an ‘ungentlemanly’ activity, as it was felt veterinary surgeons should rely on their skills and good reputation alone.

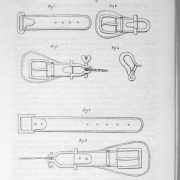

This advertising notice dates from 1902 and was created for James Best, a veterinary surgeon practising in the North Yorkshire village of Thornton-le-Dale. Best had details of his services printed on paper and mounted onto card. There’s a short piece of string at the top so it could be hung up on display. Unfortunately, the item has since broken into three pieces – it appears the poster has been folded into three, and these folds have weakened over time. Back in 1902 this advertisement proved controversial for Best.

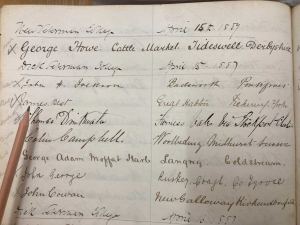

Best graduated from Edinburgh in April 1887 and began to practise in Great Habton, North Yorkshire. In 1902 he relocated to the nearby village of Thornton-le-Dale. His surgery was on High Street, the main road running through the village. Within a few months of arriving, Best arranged for several advertising notices to be placed around the neighbouring market town of Pickering.

However, an RCVS byelaw (then known as Byelaw113) stated the creation of adverts “…relating to their professional attainments or abilities or charges …amounts to conduct disgraceful in a professional respect…”. Best’s actions were brought to the attention of RCVS Council using a Registration Committee form dated 3 November 1902. From information contained in the form it seems the author was a local veterinary surgeon named Randal Copeland Bell. Our Registers tell us that Bell graduated from the Royal Veterinary College in 1899 and himself only moved to Pickering earlier in 1902 having initially practised in Scarborough.

Bell states he is aware of three advertisements left in Pickering: one in the window of a private house, and two others displayed in hotels in the town – the Black Swan and the White Swan. The notice in our archive was taken by Bell from the White Swan and sent to the Committee. Bell sounds indignant, writing that Best “…has not only used the fact that he is well known to the farmers and others in the district as a means to obtaining their work but has also advertised and started a branch office”. Local trade directories for this time list many farmers and cattle dealers in the area, and Best’s adverts must have felt like a threat to Bell’s livelihood.

Soon afterwards Best was contacted by the RCVS. In his response dated 7 November, Best gives his “…sincerest assurance, my heartfelt desire is to work in the interests of the profession [and] to look upon the laws of the Council…” But he also expresses his surprise at these events and asks “By whom is there any complaint made[?] Is it professionally or has it been some ill-disposed person or persons”. Best is perhaps concerned for his local reputation, and, like Bell, has his livelihood to consider. Presumably the RCVS did not disclose Bell’s name but, even so, apart from Best and Bell, the only other veterinary surgeon registered in the area at this time was the retired gentleman whose practice Bell took over. Best must have known of Bell’s existence and considered him the possible instigator of this grievance.

By 14 January 1903, Best is responding again to the RCVS, with a letter that tells us something of how the RCVS dealt with the matter. It appears the Registration Committee asked for written assurance that Best had stopped his advertising and taken down the notices. Though Best makes the former assurance, he has not checked whether any of the “dozen cards” are still in place. Theoretically, therefore, he is still advertising his services. In this letter he again raises the issue of the instigator stating “I am informed on good authority that a professional neighbour is reporting those things and publicly talking how he will have the cards abolished.” Bell is his nearest professional neighbour, so Best may have had Bell in mind.

Best also uses his 14 January letter to justify his activities, questioning how his actions differ from “…professional gentlemen writing to papers & giving both public information & treatment”. He gives the example of a recent lecture by a Colonel Steel who in answer to a question from the audience offered to visit their home and take a look at their animals. Best states “…it is all very well but it appears a many of us isolated mere existing beings must run risk of infringing Byelaw 113 or else starve.” Perhaps the difference in these cases is that Best’s advertisements are deliberate and unambiguous. He is touting for trade, attempting to widen his geographical reach beyond Thornton-le-Dale. The contemporary Council minute book shows there was at least one other case of unethical advertising being considered at this time, so Best was not alone in testing the limits of good behaviour in this way.

Since the introduction of the Veterinary Surgeons Act in 1881, the RCVS and its disciplinary committee investigated over 500 examples of advertising including newspaper adverts, circulars and excessive signage. These cases noticeably dropped off after 1965 when such marketing seems to have been considered less of an issue.

Best seems to have incurred no further penalty, and continued his Thornton-le-Dale practice until his death in May 1923. Similarly, Bell remained in Pickering until 1912, when he moved to Australia to work as Chief Veterinary Inspector at the Department of Public Health in Sydney. Therefore, from the initial incident in 1902, Best and Bell spent a further ten years working in neighbouring communities. We can only wonder whether the two ever met and what animosity remained.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!