Dating from around 1912 this poster advertises the veterinary skills of Mohammed Ayoub Khan and his son Mashuk Ali, two practitioners working in Meerut City, in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. The document features a range of testimonials from satisfied customers, as well as forty-four illustrations depicting successful procedures.

At this time veterinary practitioners in India were known as Salutri, a term which has its origins in the name Shalihotra. Shalihotra was a prominent authority on horse medicine working in the 3rd century BCE. His book, Shalihotra Samhita (The Collection of Shalihotra), a treatise on equine and elephant anatomy, disease, surgery and preventative care, is widely regarded as one of the foundational works of Indian veterinary literature.

Ayoub Khan worked in the town of Jalalpur, in Uttar Pradesh. Between June 1889 and July 1890, he assisted with veterinary procedures at the British Army’s North-Western Provinces Depot at Babugarh near Hapur. At this time, it was common for remount depots to recruit local veterinary practitioners to work alongside the British military, utilising their skills in equine care as well as their knowledge of the local horse-trading market. Ayoub passed his final examination in August 1890.

He subsequently expanded his practice, gaining popularity among the British community living and working nearby. The forty-one testimonies featured on the poster date from between 1894 and 1912, and as such create a snapshot of the British presence in the area at this time. Those featured include Captain WM MacLeod of the 31st Duke of Connaught’s Own Lancers, who in 1910 stated “I can testify to the invariable care and attention [Ayoub] pays to his patients and I can confidently recommend him as a thoroughly practical and skilful Doctor”. Tributes also come from the highest army ranks, such as Lieutenant-Colonel WS Mordalls of the same regiment who in 1907 wrote “… he not only treats dog ailments most skilfully but the comfort and welfare of dogs looked after in his hospital with kindness and care”. Indeed, the compassion the two Salutri have for the animals is a repeated theme of these testimonials.

In 1904 the Salutri saved the horse belonging to the engineer GID Taylor from choking, which presumably required an emergency procedure.

The Salutri’s clients also include British civilians employed in the area, such as magistrates, the Superintendent of Police, and engineers working on the Ganges Canal. Other notables paying tribute include Prince Mohammad Moosa Khan, son of the Amir of Kabul, whose horse they treated after a shaft of wood pierced its side. Interestingly this is the only testimonial in Hindi.

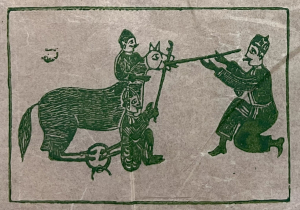

The poster includes evocative illustrations of the two Salutri at work. Most of the animals being treated are military dogs and horses. In 1906 the dog of Major Boileau of the 5th Cavalry was brought to Mashuk Ali “…practically in a dying state suffering from double Pneumonia he could not move and would touch no food and was one mass of bones”. Mashuk Ali restored the dog back to health, to the considerable delight of the Major. Equine ailments featured include poisoning, fever and a Melanosis tumour. In 1904 the horse of an Executive Engineer was treated for colic and was “…only saved by the prompt attention of the Salutri”.

The Salutri treated a range of other species, including the cow of a retired Civil Surgeon and an ox with rheumatism belonging to a district judge. Most unusual of all is the case of a panther cub with a prolapsed anus brought for treatment by a lieutenant in the 60th Rides regiment in 1909. The lieutenant testifies that “…the panther has now quite recovered”. All in a day’s work for Mashuk Ali.

Ayoub Khan treated the dog of Commissioner Reynolds in 1910 for liver growth. “I did not expect her to pull through but …. his skilful treatment effected a cure”.

The document also gives us brief insights into their working methods. For example, the Salutri used a system of “No Cure, No Pay”. This suggests not only that they were confident their methods would get results, but also that they were sufficiently successful for the two to make a living this way. Indeed, several illustrations feature additional people assisting with treatment, suggesting there were other workers whose livelihood depended on the Salutri.

Though the document is an interesting window into a different time, it nonetheless raises many questions. If we assume the advert was aimed at gaining more business from British clients (it being predominantly in English), was another version produced in Hindi? Was it usual for a Salutri to advertise in this way? Was it a controversial decision for a Salutri to assist the British, as Ayoub Khan did at the remount depot? And how did this item arrive at the RCVS archives? It was perhaps most likely brought to Britain by a military vet, but we don’t know who they were or whether it was originally part of a larger collection. For now, we must make do with this single witness to the work of these two fine Salutri.