Early veterinary education in North America – the Scottish connection

In the early days of the RCVS it was not unusual for Council, and other members, to go ‘on tour’ to visit ‘continental veterinary schools’. It is perhaps as a result of these trips that we have a small collection of late nineteenth and early twentieth century prospectuses from North American veterinary schools in the Historical Collection.

In his paper on the beginnings of veterinary education in North America Donald F Smith1 notes that many of the first colleges were privately owned, for profit, institutions started by veterinary entrepreneurs.

The prospectuses in our collection show that a number of these veterinary entrepreneurs were graduates of Scottish veterinary schools. We also find Scottish graduates heading veterinary facilities at universities. For example:

- Montreal Veterinary College opened in 1866 by Duncan McNab McEachran (graduated Edinburgh 1861);

- The veterinary department at Harvard University run by Charles Parker Lynman (Edinburgh. 1874) from 1882 until it’s closure in 1902;

- Chicago Veterinary School founded by Joseph Hughes (Glasgow 1882) in 1883;

- Cornell University’s veterinary faculty formed by James Law (Edinburgh 1861) in 1895; and

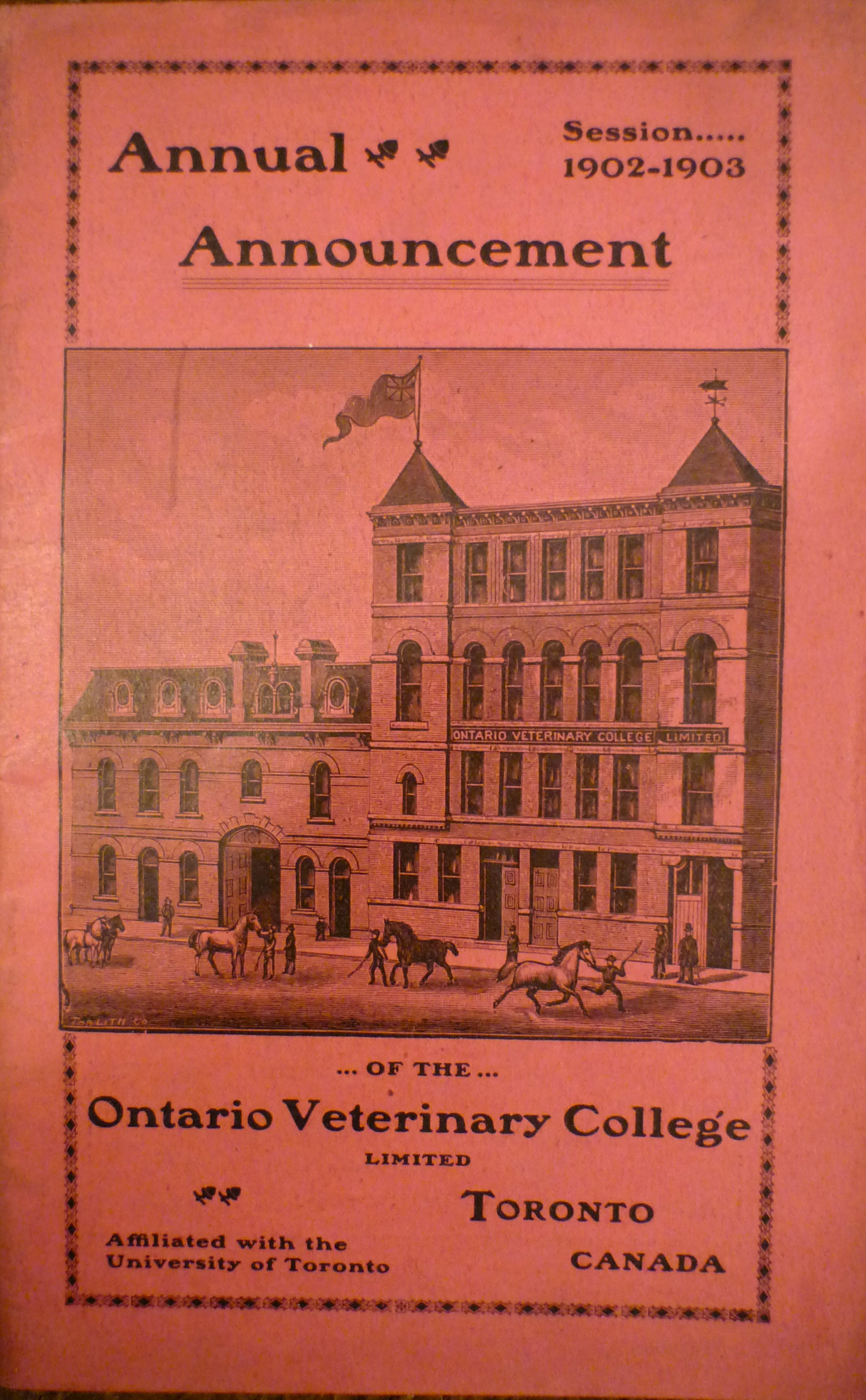

- Ontario Veterinary College (OVC) Toronto founded in 1862 by Andrew Smith.

Andrew Smith (1834-1910) was another Edinburgh graduate (1861) and a Fellow of the RCVS (1886).

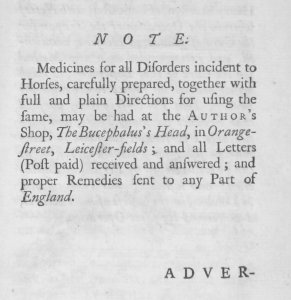

His arrival in Canada followed a visit by the Ontario Board of Agriculture to Professor William Dick in Edinburgh; they were concerned about the plagues that were devastating European cattle and wanted his advice. Dick suggested Smith as a suitable person to lecture on veterinary science (he had graduated the previous year with the ‘highest honour’).

As a result of this recommendation Smith was hired, emigrated to Canada and began a series of lectures which soon developed into a formal course of instruction. The first three students graduated from OVC in 1866.

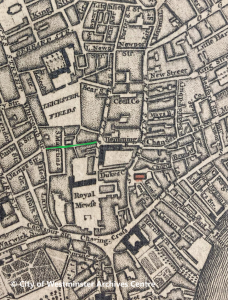

The College quickly grew, with Smith financing the building of its first home on Temperance Street in 1870. The continuing growth in student numbers meant that the building needed to be enlarged in 1876 and again in 1889. In 1897 OVC affiliated with the University of Toronto.

Smith’s connection with OVC, which lasted 46 years, ended when the government of Ontario acquired the College in 1908. By this time over 3,000 students had graduated from OVC.

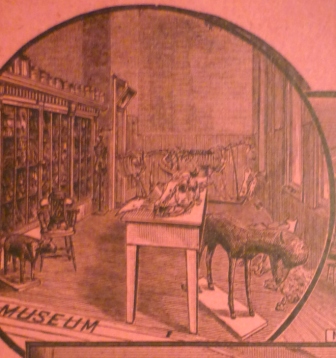

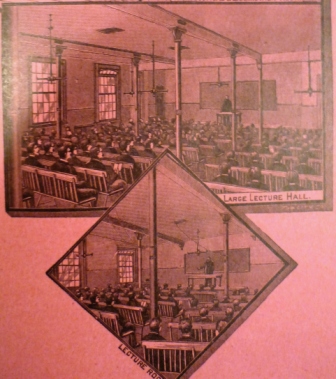

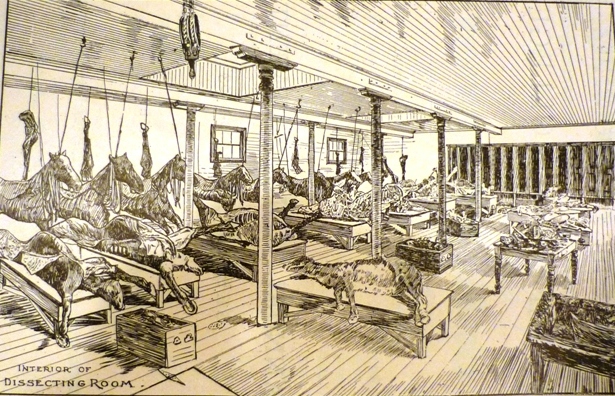

The following images are taken from the 1902-1903 prospectus and show something of the facilities on offer to students at that time. I particularly like the picture of the dissecting room – in his article Smith1 records that on one occasion OVC students lassoed a pedestrian walking along the street below, hauled him up to the second floor dissection room before laying him out on the table as a specimen. Apparently they were so scared that they would be reported that they locked the unfortunate gentleman in a horse ambulance until he swore that he would keep quiet!

Information on the history of OVC after Andrew Smith can be found here.

References

- Smith, Donald F (2010) 150th anniversary of veterinary education and the veterinary profession in North America Journal of Veterinary Medical Education. Vol 37 No 4 pp317-27.

- Jones, Bruce Vivash (2013) Establishing veterinary education in North America Veterinary Record Vol 172 No 2 pp36-38

- Miller, Everett B (1981) Private veterinary colleges in the United States, 1852-1927 Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association Vol 178 No 6 pp583-393