51 – Letter to Fred Bullock from Frederick Smith, 26 Nov 1922

The copyright of this material belongs to the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons. It is available for reuse under a Creative Commons, Attribution, Non-commercial license.

Help more people find this work! Suggest a tag via the form:

London, like most towns or cities, has lots of plaques commemorating people or events attached to its buildings. Most of these plaques are above eye level and often go unnoticed by people passing by.

One such plaque is sited on the left-hand side of Oxford Street, when walking down from Marble Arch, on the block just before Portman Street. As you can see from the photo above – it is quite hard to spot as it is small, high up and surrounded by garish shop displays.

A close up of the plaque, which was erected by the Veterinary History Society in 1982, reveals that it commemorates the fact that William Moorcroft, veterinary surgeon, lived and practiced on the site from 1793-1808.

William Moorcroft 1767-1825 was born in Ormskirk, Lancashire the grandson of a wealthy landowner and farmer. In the early 1780s he was apprenticed to a surgeon in Liverpool but during an outbreak of an unknown cattle disease he was recruited to help treat the stricken animals. Moorcroft impressed the local landowners so much that they offered to underwrite his education if he gave up his plans to study surgery and went instead to the veterinary school in Lyon, France.

This he did, arriving in France in 1789, graduating a year or so later as the first Englishman to qualify as a veterinary surgeon.

Returning to London he set up in practice at 224 Oxford Street (the street has since been renumbered). In 1794 Moorcroft was made joint Professor, with Edward Coleman, of the London Veterinary College. However the arrangement only lasted a few weeks before he resigned seemingly because of the difficulties of combining academic life with a thriving business. The Oxford Street practice continued to grow, with Moorcroft recruiting John Field, firstly as his assistant and then later as his partner, until it became one of the most lucrative in London.

As well as his work in the practice Moorcroft also purchased breeding stock for the East India Company and in 1803 was appointed manager of their stud in Essex. Then in 1808 he was appointed as Superintendent of the East India Company’s stud in Bengal at a salary of £3,000 a year (the size of the salary offered to Moorcroft gives some indication of just how successful the practice must have been).

Thus began the part of his life for which Moorcroft is perhaps better known. As well as improving the control of disease in the stud in Bengal he established a number of subsidiary studs and introduced a co-operative breeding programme with the local population. However the breeding programme still did not produce the type of horse that was needed for cavalry and artillery purposes and Moorcroft began to look further afield.

In 1811 he travelled some 1500 miles across North India looking for new breeding stock. Then in May 1812 he set out on a second journey, with Captain Hyder Hearsey, this time looking for both horses and as a side issue the Tibetan shawl goat. (Moorcroft saw the goat as offering an opportunity for increased trade between the company and the locals).

Their journey took them through Kumaon and the Niti Pass into Tibet, finally ending at Lake Manasarovar, and resulted in the purchase of Kashmir goats, some of which eventually ended up in Scotland, but little in the way of horses. Perhaps not surprisingly Moorcroft’s employers were not impressed – his primary purpose had been to look for horses and he came back with goats! – and they curtailed his travels for a number of years.

In 1819 Moorcroft embarked on what was to be his final – 6 year long – journey. Visiting Ladakh (1820-1822), Kasmir and the Punjab (1822-1823), Afghanistan (1824-1824), Turkestan (1824-1825), finally reaching Bokhara, in modern Uzbekistan, on 25th February 1825. He died from fever on the return journey on 27 August 1825.

William Moorcroft, – pioneering veterinary surgeon and Asian explorer – quite a story which the plaque only hints at. Want to find out more? Then check out some of the books listed below.

Further reading

Alder, Garry (1985) Beyond Bokhara : The Life Of William Moorcroft, Asian Explorer And Pioneer Veterinary Surgeon, 1767-1825 London: Century Publishing

Irwin, John (1973) The Kashmir shawl London : HMSO

Travels in the Himalayan Provinces of Hindustan and the Punjab, in Ladakh and Kashnair, in Peshawur, Kabul, Kunduz and Bokhara, from 1819 to 1825: by William Moorcroft and George Trebeck: prepared from the press from original journals and correspondence by H. H. Wilson. London: 1845 (reprinted New Delhi : Sagar Publications 1971)

Recently there has been another of those coincidences that those of us who work in libraries love. Two quite separate enquiries which end up having something – or in this case someone – in common.

The first enquiry was from a researcher who wanted to look at The quarterly journal of veterinary science in India and army animal management and the second from someone who was researching James McCall, founder of Glasgow Veterinary College.

The connection? John Henry Steel – who was the co-founder of the journal and who had a medal named after him which was awarded to McCall in 1899.

As is usual when this happens curiosity got the better of me and I had to find out more..

John Henry Steel FRCVS (1855-1891) followed his father into the veterinary profession, graduating from the London Veterinary College in 1875. After a brief spell in the army he took up a post as Demonstrator of Anatomy at the London College where he remained for five years, before resigning when the professorship, which he had been promised, was abolished.

He re-entered the army and, in 1882, went to serve in India, which was to be the scene of his most notable achievements. Upon arrival, he “was immediately impressed by the utter want, outside the Army, of anything approaching Veterinary Science” and set about rectifying the situation.

One of his first moves was to establish, in 1883, The quarterly journal of veterinary science in India and army animal management. This journal, which he co-founded with Frederick Smith, allowed vets to share information and record progress in treatments etc.

Secondly, in 1886, he established a veterinary college in Bombay so that the population could be “educated in veterinary matters”.

Sadly the severe mental and physical strain of running the journal and the College took its toll and he was taken ill, returning to England in 1888. Against the advice of doctors, he went back to India after a few months and involved himself fully in the life of Bombay, taking up the reins at the College again and becoming a Fellow of the University and a JP.

His health did not improve and, seemingly aware of his imminent death, he wrote an editorial for the journal, dated October 1890, titled ‘Cui Bono’ (to whose benefit?). It starts:

“To every conscientious worker there arrive times of introspection when the questions arise to him what has been the outcome of my efforts?”

Steel then proceeds to assess his life’s work and in particular to question the usefulness of the Journal and whether it was worth the “at times laborious work”.

He feels

“it has succeeded in enlarging the mind of the public and profession on matters veterinary…[and has] enabled men working on the same subjects… to co-ordinate their work and results”

and if at all possible it must continue

“Considering how things were before the Quarterly, considering the work our Journal has been enabled to do…we have decided to continue its production”

Sadly this was not to be and Steel wrote an announcement stating that owing to severe illness he was having to leave India and that the Journal will no longer be continued after December 1890. The publisher then adds to the end of the announcement, which was distributed with the last issue, “J H Steel, Esq …died at Bombay on Thursday the 8th”.

He was just short of his 36th birthday.

The three page obituary in the Veterinary Record (31 January 1891), from which the title of this post is taken, and the fact that the RCVS instituted a medal in his honour testifies to the high regard in which he was held by the profession.

The College which he founded, the Journal and his books on diseases of the ox, dog, elephant, sheep, and camel and on equine relapsing fever remain as his lasting legacy.

In Volume 5 of The quarterly journal of veterinary science in India, published in 1887, there is a two part article by T J Symonds ‘Illustrations of Indian materia medica’.

Thomas J Symonds (?-1892) graduated from the London Veterinary College in December 1870. He entered the Army Veterinary Department in March 1871 and served in the Afghan War 1880-1881; taking part in the march from Quetta as part of the relief of Kandahar. At the time of his death Symonds was involved in purchasing remounts for the government in Madras.

His obituary in the South of India Observer (reprinted in The Veterinarian September 1892) says that he was ‘engaged in literary work for a portion of his professional career and was the author of some books connected with professional subjects’. We have several of Symonds’ books in our historical collection which are all about plants and their use as material medica

Saunders Comprehensive Veterinary Dictionary (3rd ed 2007) defines materia medica as:

“the study of materials used in medicine. It used to be a subject in veterinary curricula and dealt mostly with the physical and chemical characteristics of the medicinal substances. As a science it has now been largely superseded by pharmacology”.

Given that materia medica was taught in the veterinary schools it is not surprising that the early journals contain lots of information on plants and their use as veterinary medicines. For me Symonds’ article stands out because of the full page colour illustrations that accompany the text

Aloe Indica –. ‘[its] juice … gives an inferior kind of drug’

Calotropsis Gigantea –useful in diarrhoea, dysentery and chronic rheumatism

Cinchona Officinalis – its bark can be used in the treatment of fevers.

Azadirachta Indica – used as a poultice to relieve nervous headaches, the juice of the leaves are said to be anthelmintic, diuretic and to resolve swellings.

Carum (Ptychotis) Ajowan – used as an antispasmodic, carminative, tonic and stimulant

(Note how this plant is to bushy to fit on the page! The leaves stray outside the border and it is printed on a bigger sheet of paper which had to be folded to fit with the rest of the volume).

For more information on the The quarterly journal of veterinary science in India .

From February to April this year, RCVS Knowledge were very pleased to welcome Claudia Watts, an MA History student from King’s College London. As part of her studies, Claudia was tasked with selecting highlights from Fred Smith’s veterinary case notes, and digitising and transcribing them for us. The results are now published in our Digital Collections, and here Claudia shares some of her thoughts on the project.

Over the past few months, I have had the wonderful task of exploring and transcribing the incredible sources left behind by Veterinary Surgeon Frederick Smith during his time in India in the 1880s.

The further I delved into the mountain of work he left behind, I developed a clearer picture of this man; relentless, dedicated and a complete workaholic.

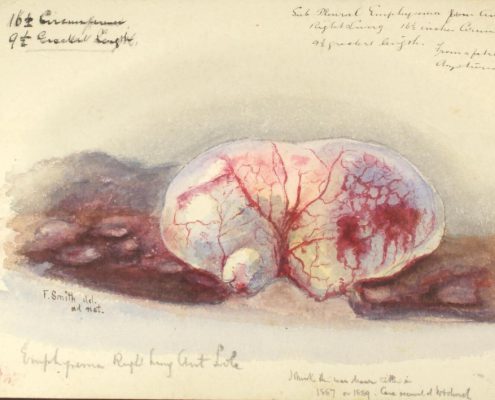

I have uncovered some truly unique treasures – often turning a page only to have my breath honestly taken away as I stumbled upon beautiful artwork (FS/2/2/2/1/7), unique photographs (FS/2/2/2/1/10) and of course mounds of fascinating case notes and reports. His work provides wonderful insight not only into the man himself, but also the workings of the Army Veterinary corps. In addition to this, it has been fascinating to see how he has used his findings and research to educate. Many case notes appearing in his articles and manuals. Within these folders are pieces of crucial veterinary history as Smith helped guide the profession, contributing to the institution today.

Sub pleural Emphysema [FS/2/2/2/1/7]

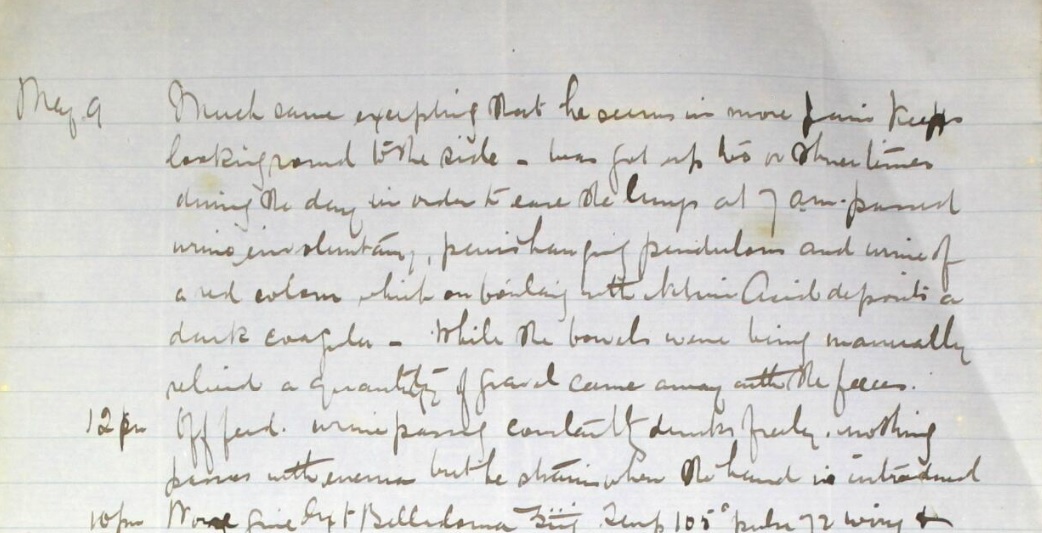

Transcribing his work has been a challenge I have never faced before, and I have a newfound appreciation for the patience and hardwork of an archivist. Smith’s handwriting, to say the least, is rather tricky! But after a few days, and then a few weeks I have cracked it. That satisfaction of becoming a specialist in one individual’s handwriting is strangely thrilling! Staring at one mystery word for an hour and triumphantly declaring “manually!! He means manually!!!” has probably caused my colleagues sitting near me a few headaches….

“was got up two or three times during the day in order to ease the lungs…” Extract from the case notes for Horse E-16 [FS/2/2/2/2/3]

At times his work left a bitter-sweet taste, as he describes horses who despite all odds cling to life. When reading his work it becomes clear he had a deep appreciation and respect for the animals in his care. A piece which has become a personal favorite of mine, comes from the folder on Fractures and Wounds. Horse E-16 while being treated:

“…suddenly wheeled round,

ran back then rushed forward, turned sharp and jumped a

Bamboo hen Coop and then started off at a mad gallop

towards the troop lines and bolted into the angle formed by

two walls dashed his head against the wall and lay doubled

Up.”

Smith includes a sketch of the horse, and states that the horse “with its characteristic facial expression enabled me to recall this case when I raised this in June 1927 namely 47 years after the event.” Despite all that time, and probably after hundreds of other horses had come under his care he remembered E-16.

Sketch of Horse E-16 [FS/2/2/2/2/3]

It truly has been an eye opening few months, and to have had the opportunity to work so closely with such wonderful materials has been a pleasure. I am so grateful to everyone at RCVS Knowledge. I hope the sources I have transcribed and digitized will be of use and potentially encourage individuals to take their own journey into these amazing resources.

by Claudia Watts, MA History, Kings College London

To explore these veterinary case notes yourselves, visit our Digital Collections website, or contact us to view the full collection in person.

We are an RCVS Knowledge initiative, for the preservation and promotion of the historical collections of the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons, made possible with the support of The Alborada Trust.

The Alborada Trust is a charitable trust founded in 2001. Its aims are the funding of medical and veterinary causes, research and education – and the relief of poverty and human and animal suffering, sickness and ill-health. Charity Registration No 1091660

Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons Trust (trading as RCVS Knowledge) is a registered Charity No. 230886. Registered as a Company limited by guarantee in England and Wales No. 598443.

Registered Office:

First Floor, 10 Queen Street Place, London EC4R 1BE

Correspondence Address:

RCVS Knowledge, 3 Waterhouse Square, 138-142 Holborn, London. EC1N 2SW

020 7202 0721

This site uses cookies. By continuing to browse the site, you are agreeing to our use of cookies. See our cookie declaration

Accept settingsHide notification onlySettingsWe may request cookies to be set on your device. We use cookies to let us know when you visit our websites, how you interact with us, to enrich your user experience, and to customize your relationship with our website.

Click on the different category headings to find out more. You can also change some of your preferences. Note that blocking some types of cookies may impact your experience on our websites and the services we are able to offer.

These cookies are strictly necessary to provide you with services available through our website and to use some of its features.

Because these cookies are strictly necessary to deliver the website, refuseing them will have impact how our site functions. You always can block or delete cookies by changing your browser settings and force blocking all cookies on this website. But this will always prompt you to accept/refuse cookies when revisiting our site.

We fully respect if you want to refuse cookies but to avoid asking you again and again kindly allow us to store a cookie for that. You are free to opt out any time or opt in for other cookies to get a better experience. If you refuse cookies we will remove all set cookies in our domain.

We provide you with a list of stored cookies on your computer in our domain so you can check what we stored. Due to security reasons we are not able to show or modify cookies from other domains. You can check these in your browser security settings.

We also use different external services like Google Webfonts, Google Maps, and external Video providers. Since these providers may collect personal data like your IP address we allow you to block them here. Please be aware that this might heavily reduce the functionality and appearance of our site. Changes will take effect once you reload the page.

Google Webfont Settings:

Google Map Settings:

Vimeo and Youtube video embeds: