“A Good Deal of Spade Work” – The RCVS Archives Project

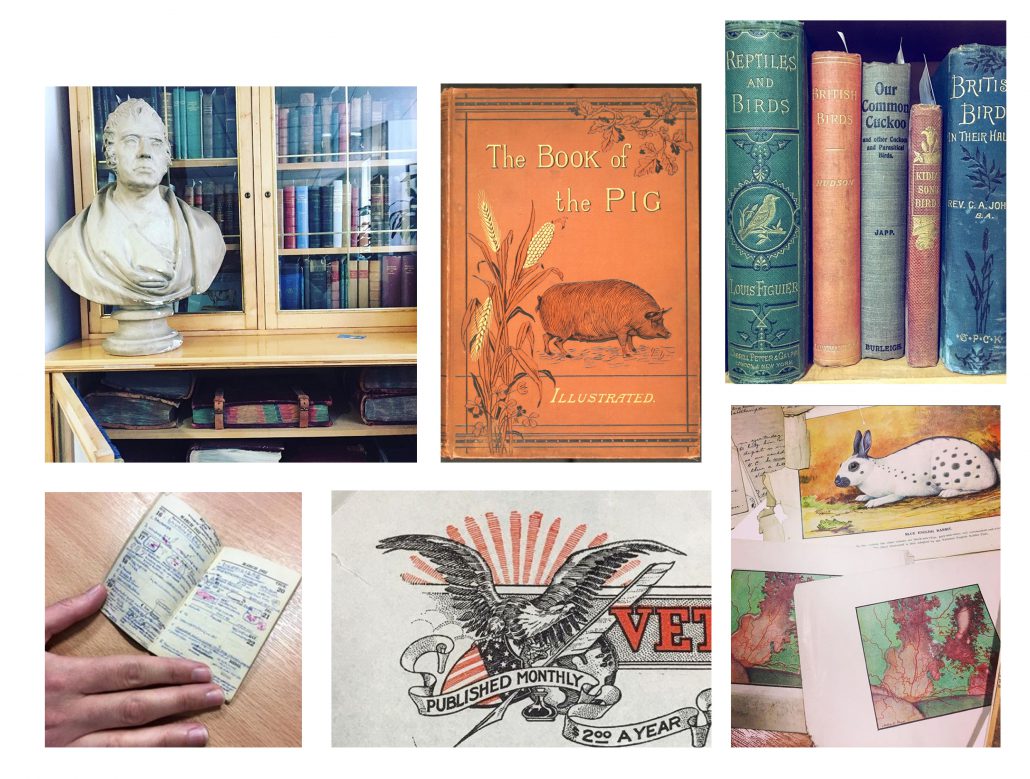

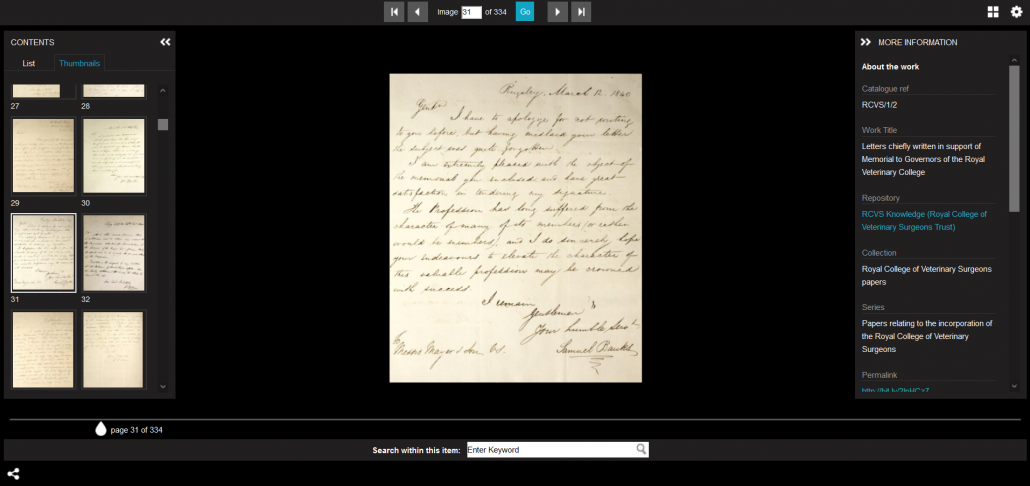

In June this year, RCVS Knowledge were thrilled to announce that the Alborada Trust had provided funding for a five year project to catalogue, preserve and digitise the Historic Collection and Archive of the Royal College. Now, five months later, it is time to update you with the progress that has been made so far!

One of the first steps of the project was to employ a qualified Archivist, to oversee the execution of the project, including the cataloguing, recruitment of a digitisation assistant, and development of the digital platform which will provide greater access to the collections.

That Archivist is me!

I’m Lorna Cahill, and I started working here at RCVS Knowledge six weeks ago. Previously I have worked in the Archives of the Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, the Natural History Museum, and Royal Holloway, University of London. I have lots of experience working with material from the 19th century, particularly relating to science and education. So this post is a perfect fit! I am incredibly excited to delve deep into these fascinating collections, and to draw out some of the stories and characters and share them with the public. I hope to regularly update this blog, and the @RCVSKnowledge Twitter feed, with interesting bits and bobs I find along the way. So keep an eye out for those.

So what have I been up to for the past six weeks – and what’s the next step of the project?

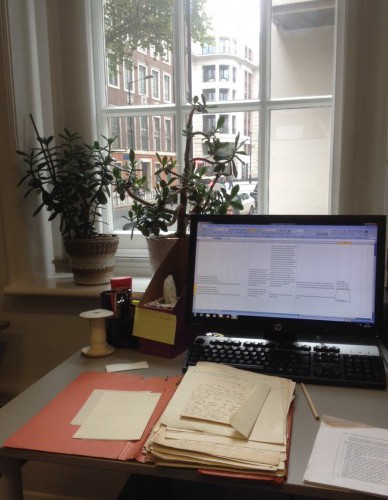

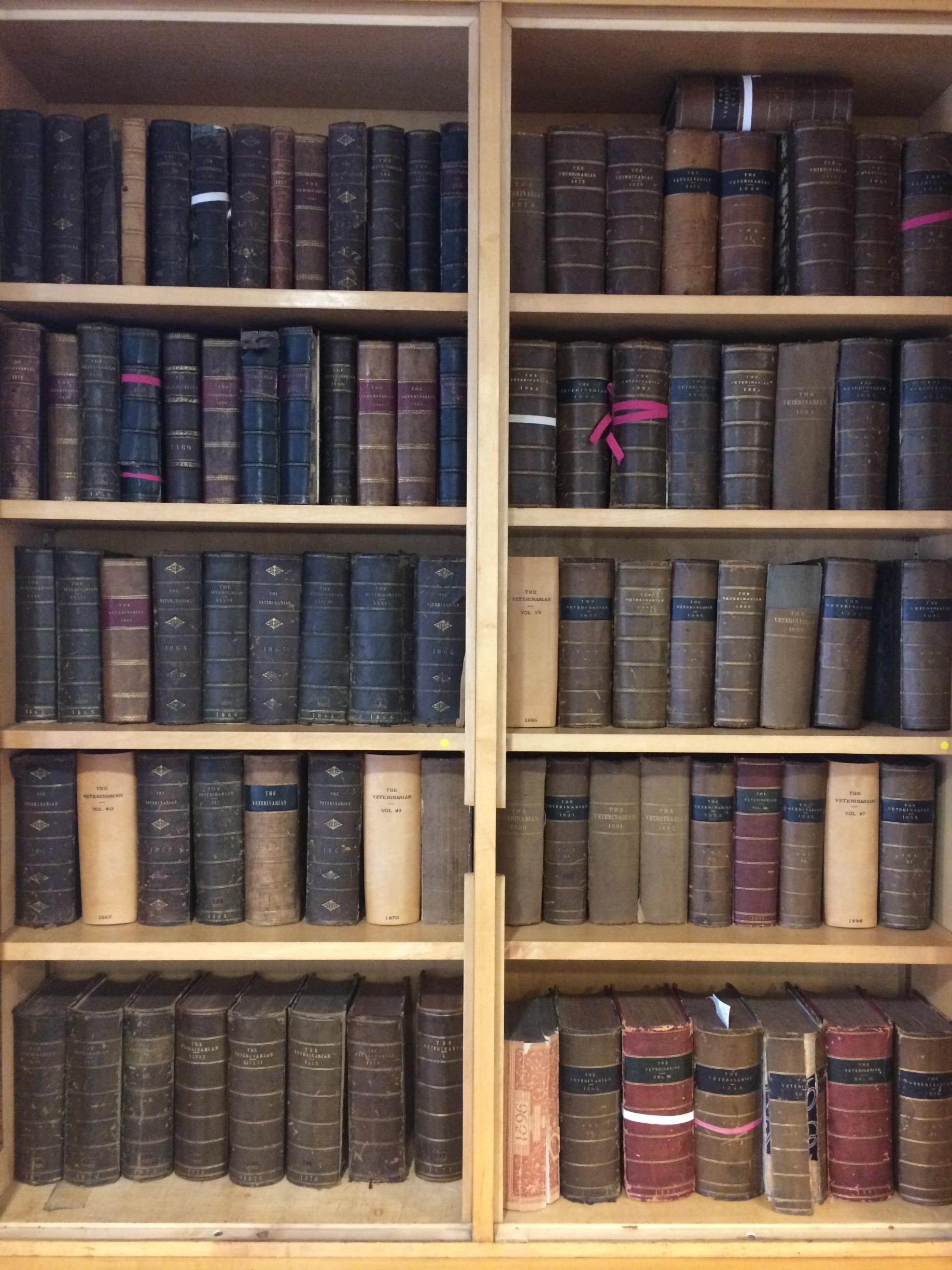

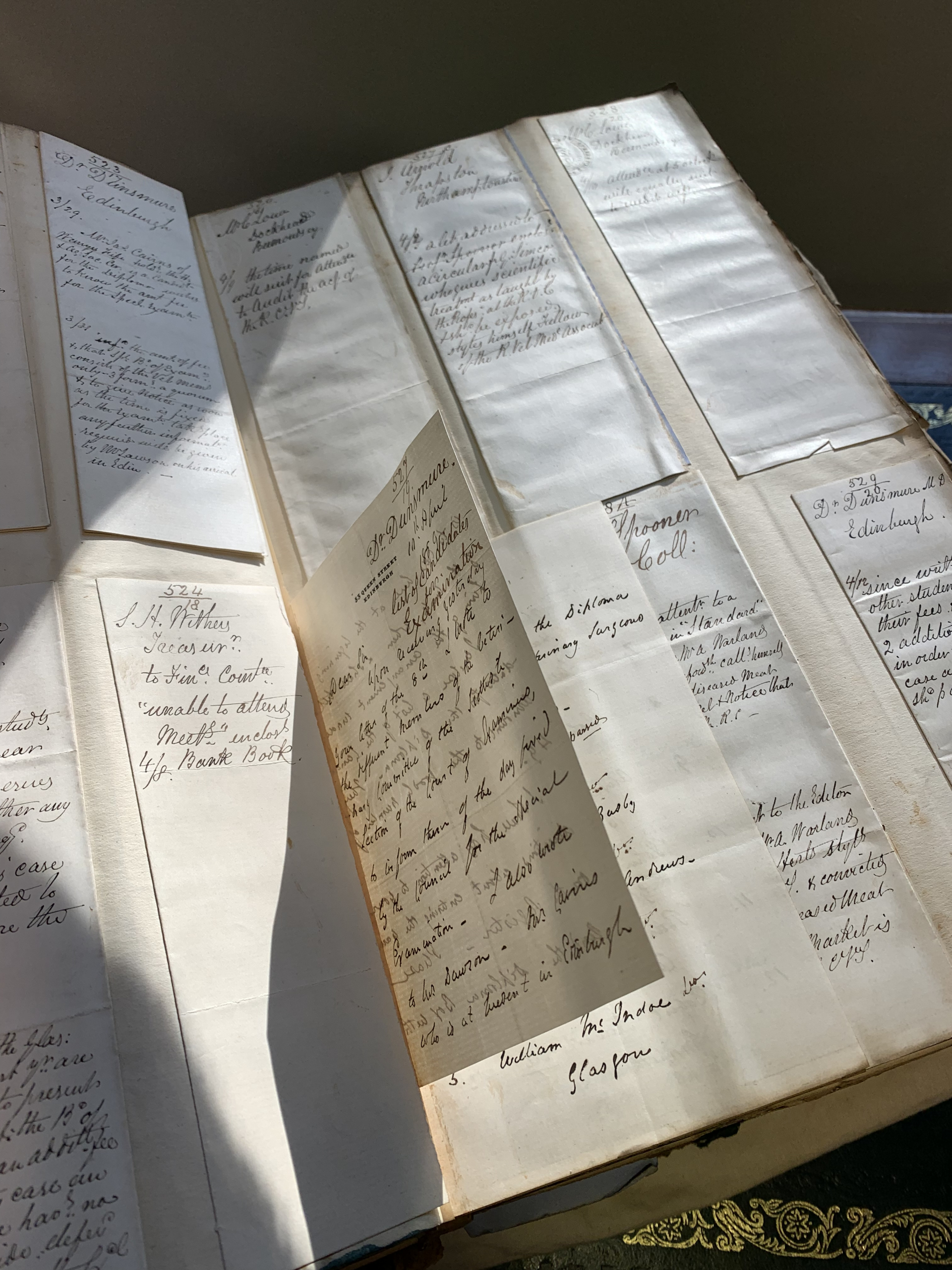

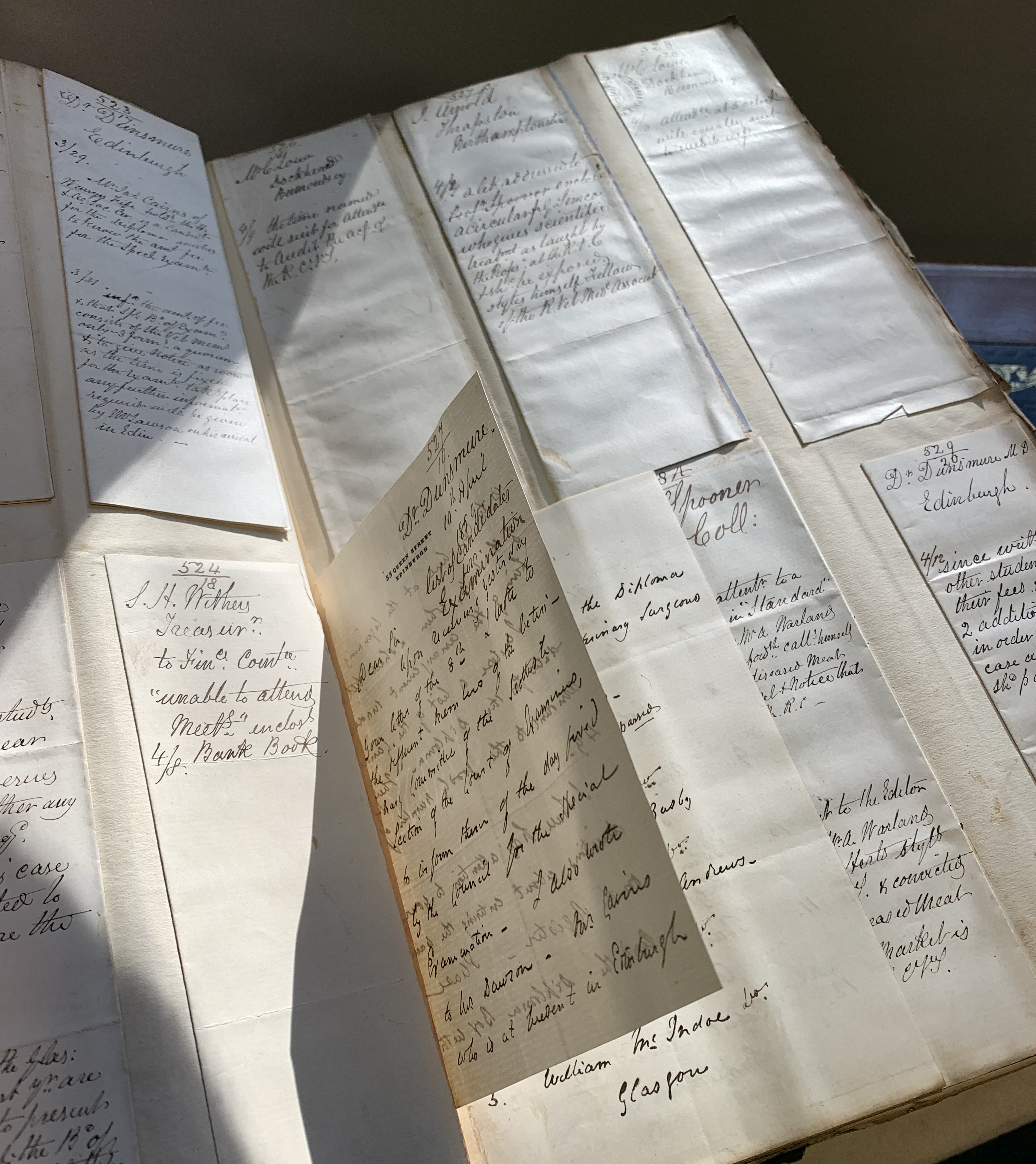

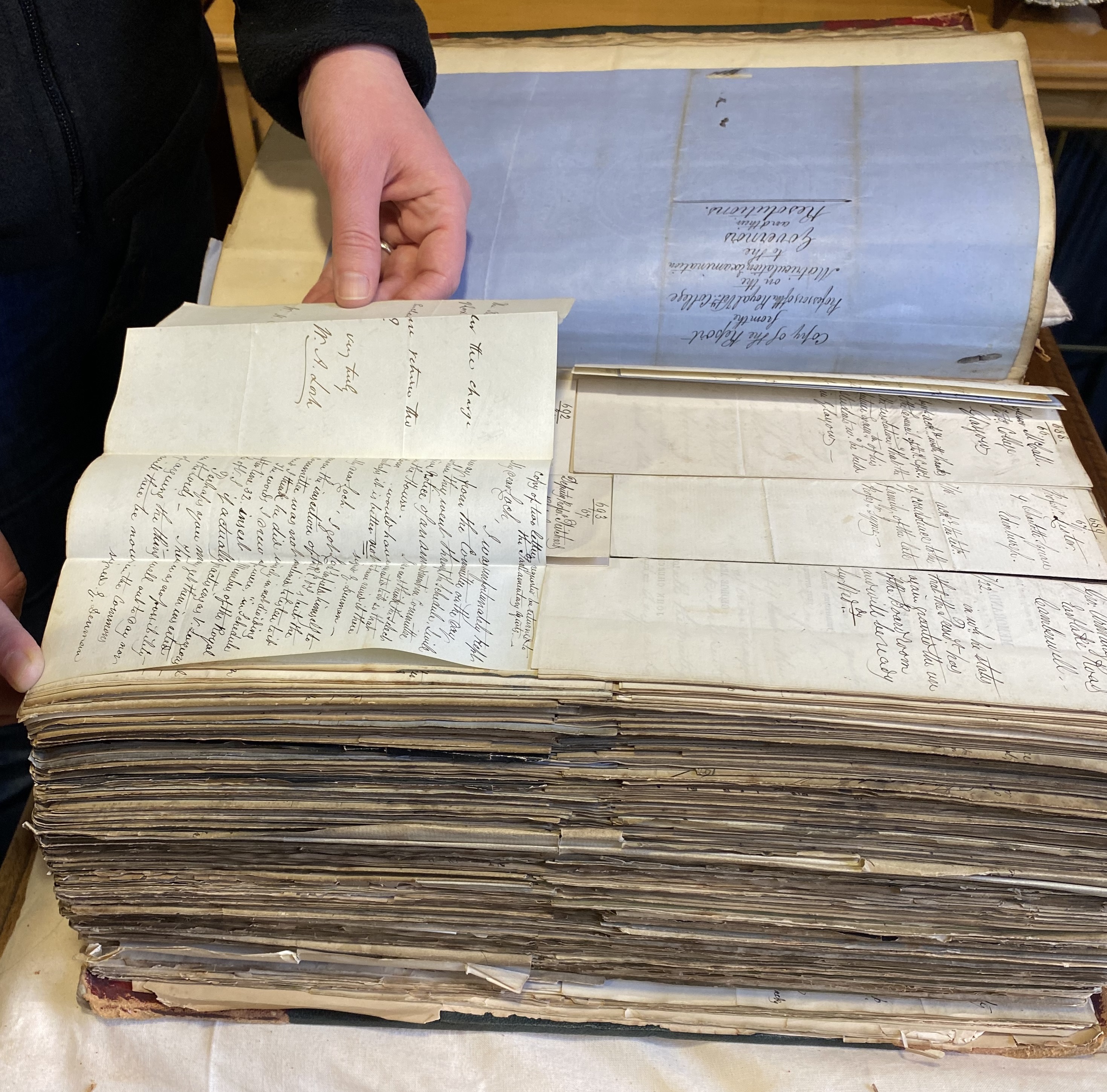

Happily for me, my main task thus far is exploring the collection. I need to get an idea of what the collections contain, the context around the material, who the people are that created the papers, and how best to look after them. It didn’t take me long to realise that I would first need boxes. Lots and lots of Archive boxes.

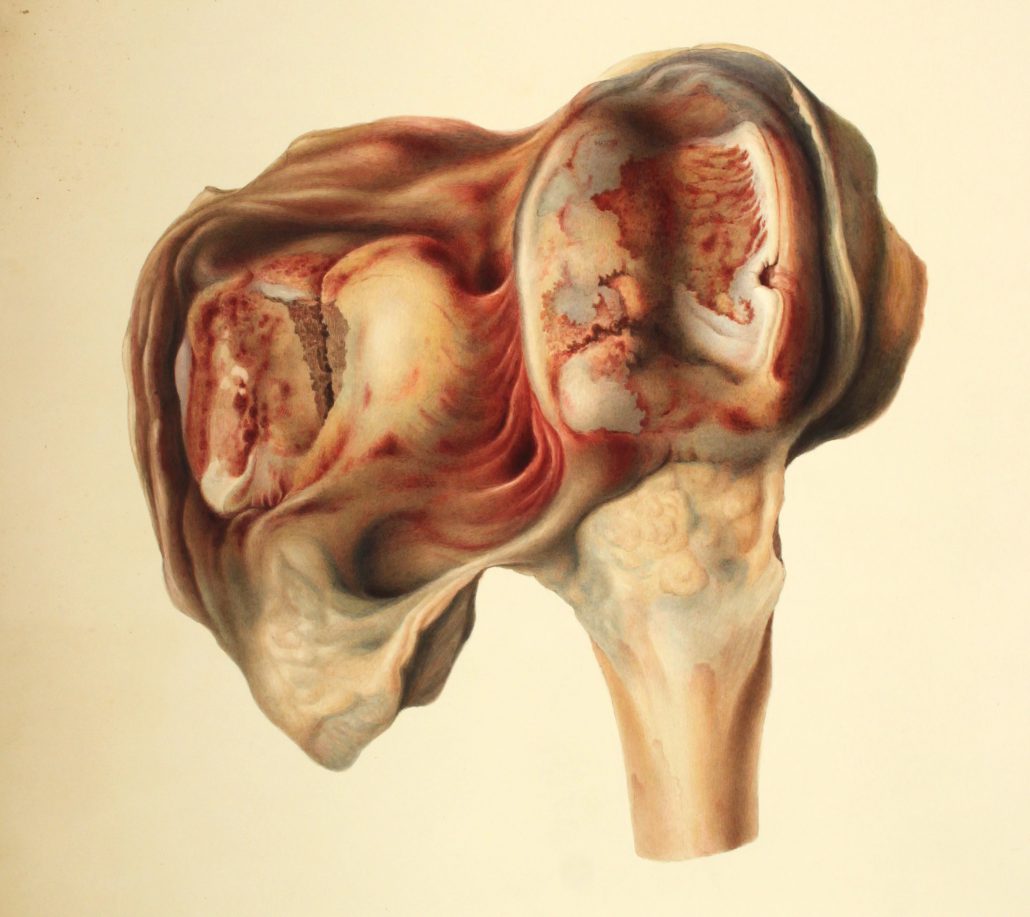

First I took a sample of papers by Connie Ford MRCVS (1912-1998), who worked for the Veterinary Investigation Service for nearly 30 years. She was a specialist in cattle fertility, and I very soon got used to reading a lot about bull testicles and cow abortions (archives work is not always so glamorous!). The research carried out by Ford seems incredibly thorough and there is a great deal of data for me to sift through. However, sometimes it can be rather touching, such as this list of cow abortions. Poor Betty, Shirley and Joyce.

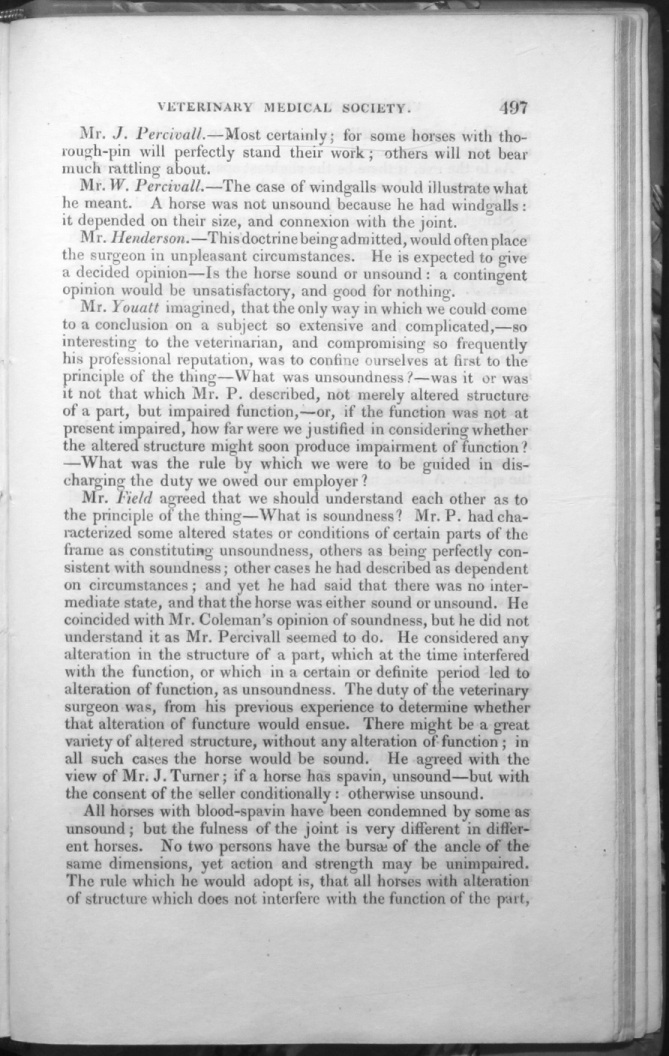

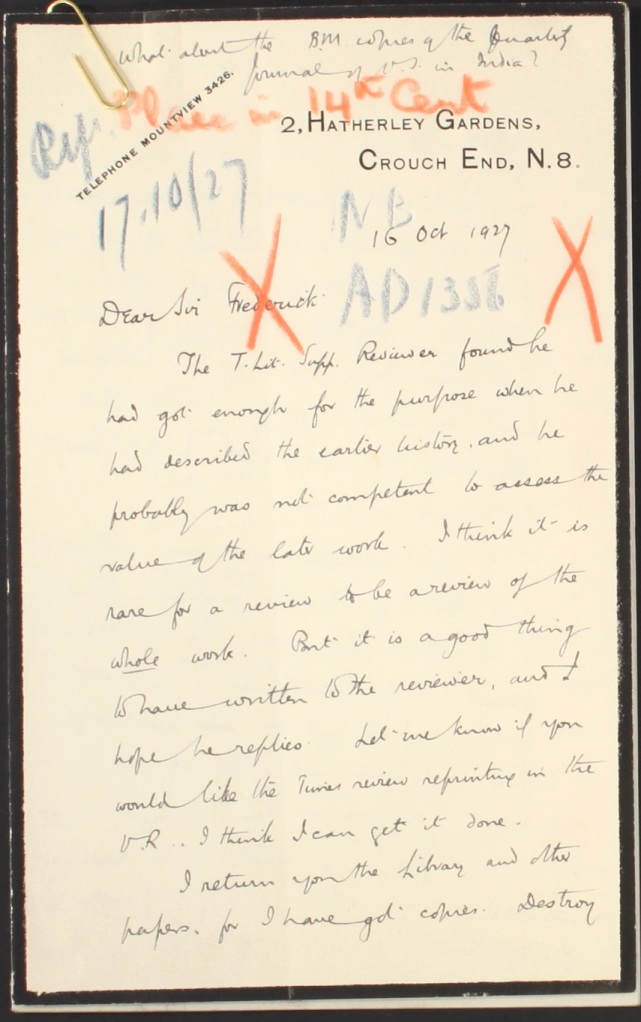

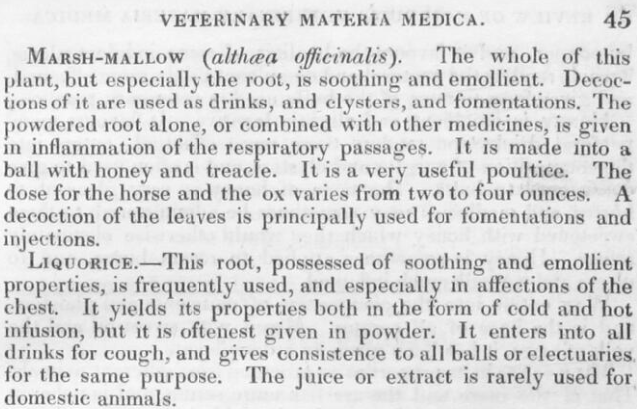

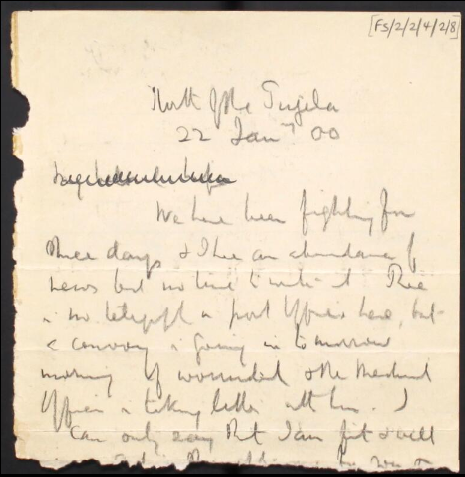

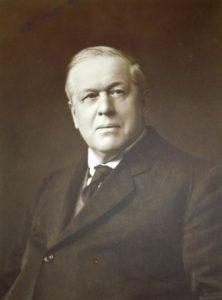

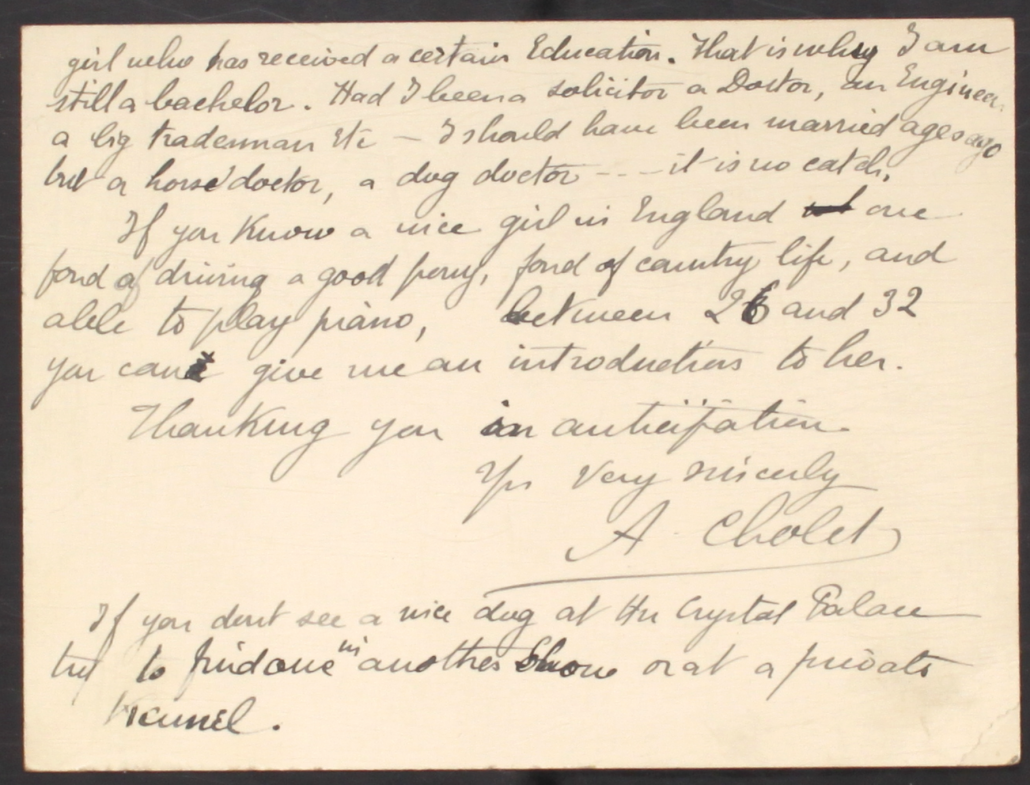

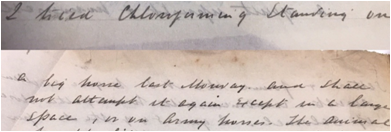

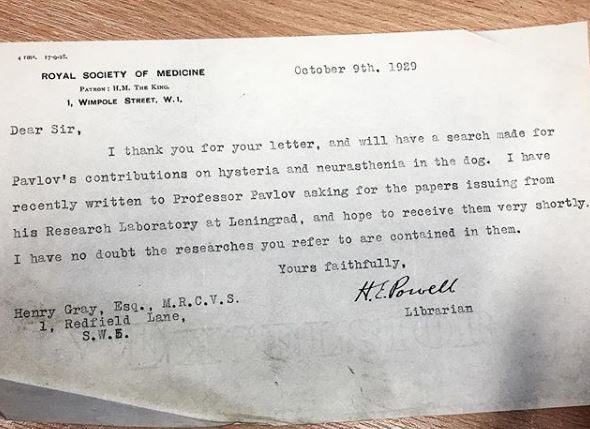

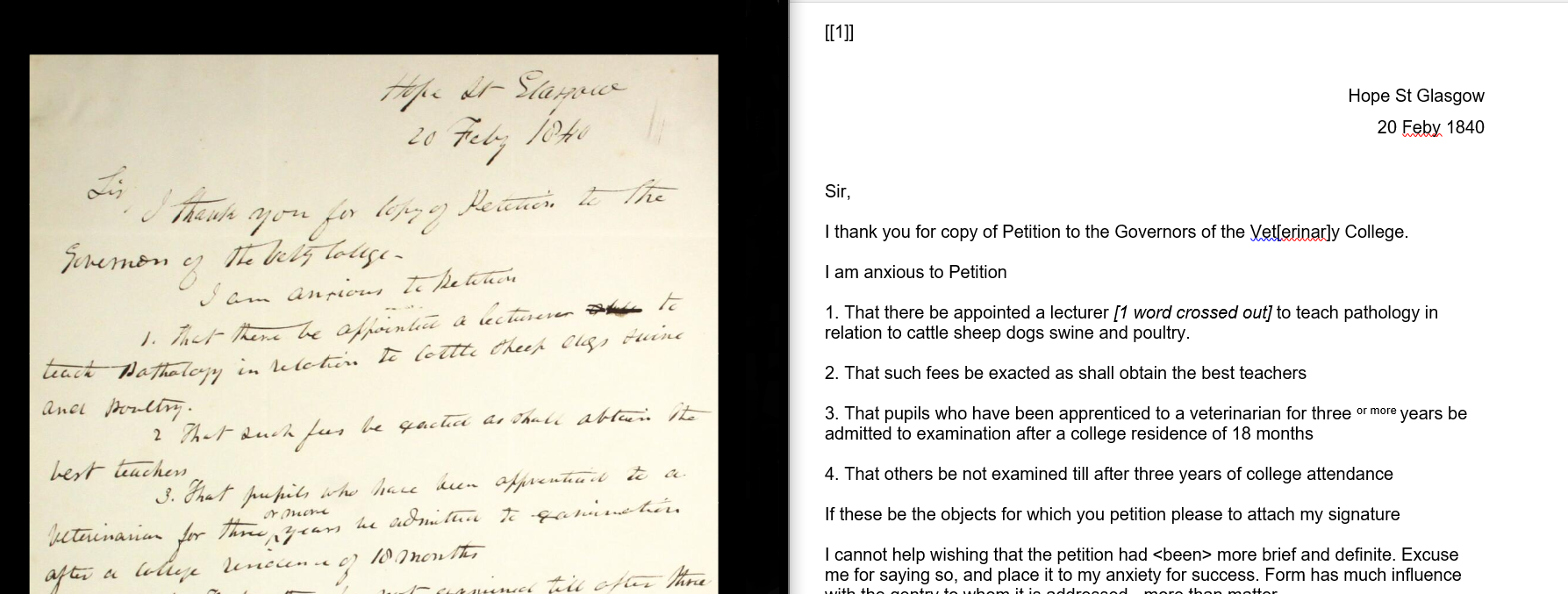

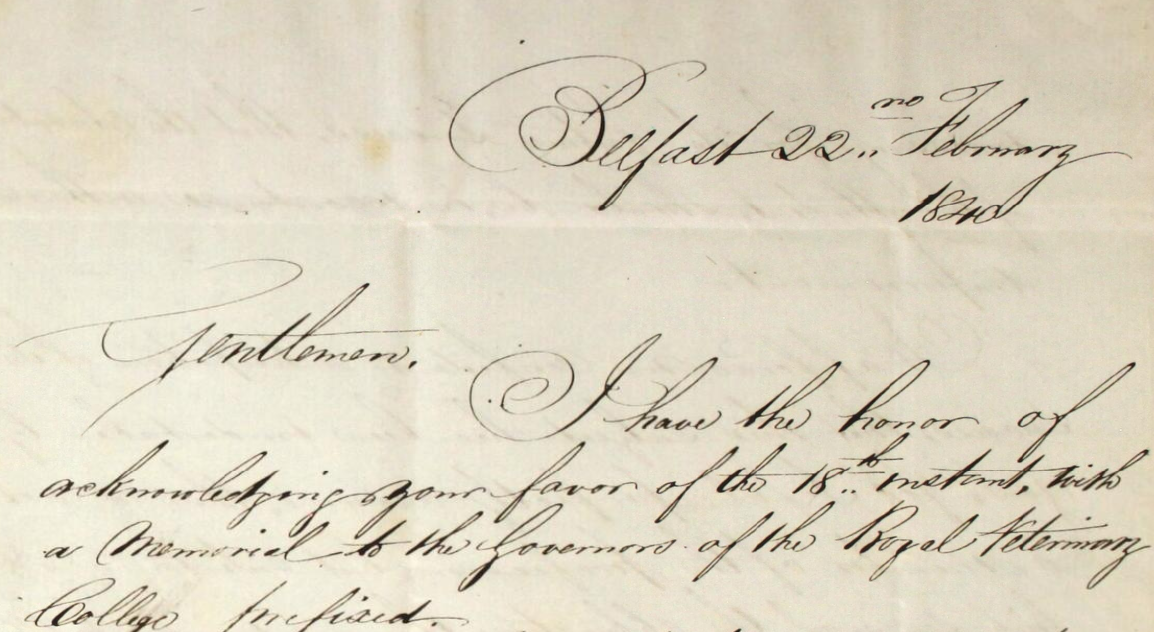

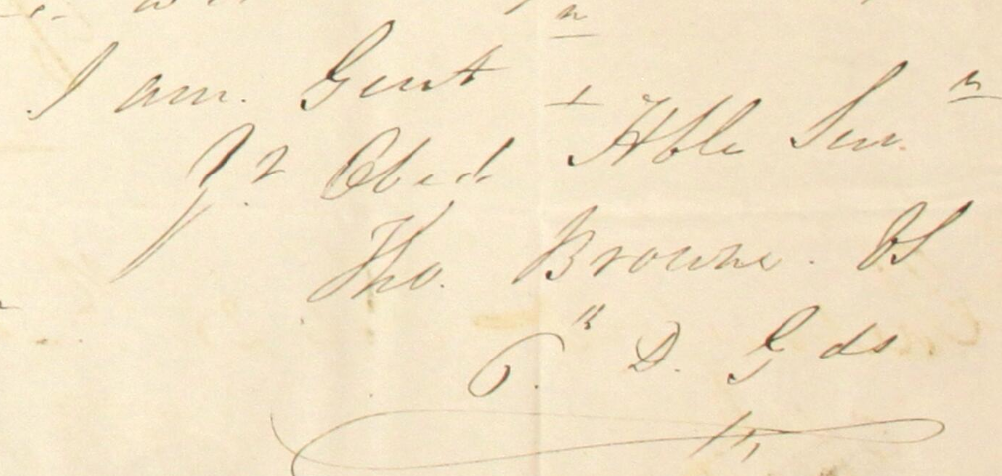

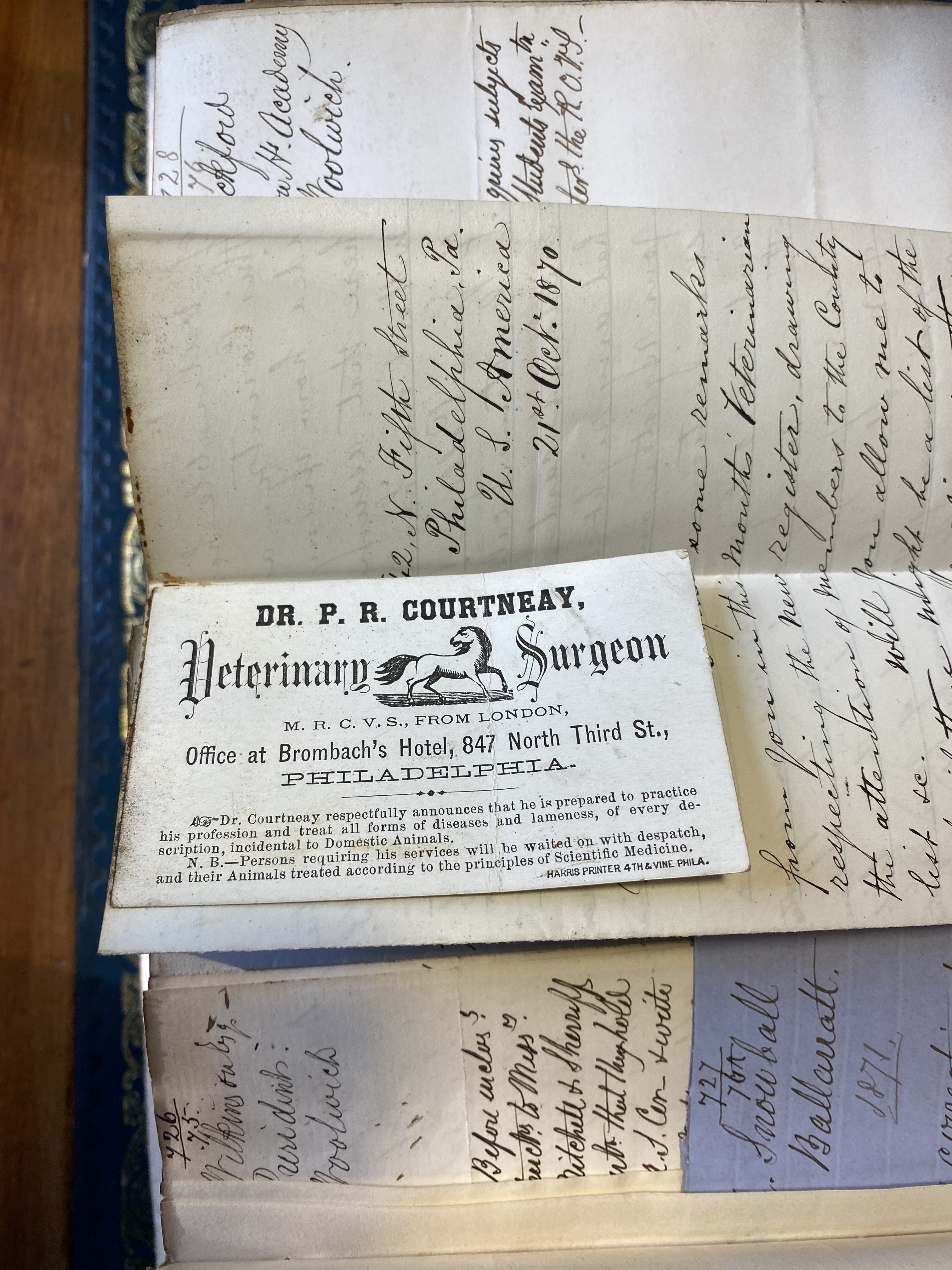

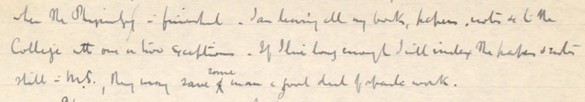

The collection I will be focussing on for the near future is that of Major General Sir Frederick Smith MRCVS (1857-1929). Smith served with the Army Veterinary Service during the Second Boer War, and was eventually appointed Director General in 1907. He wrote several veterinary manuals and histories of the veterinary profession, and carried out extensive research. I have just looked through nearly 20 years of correspondence between Smith and Fred Bullock, Secretary of RCVS, which has revealed to me a great deal about Smith’s character. I even found Smith’s prediction, in 1920, that one day I would come along to curate his papers:

“I am leaving all my books, papers, notes &c to the College with one or two exceptions. If I live long enough I will index the papers & notes still in M.S, they may save some man a good deal of spade work.”

It has taken 95 years, but finally someone is giving them all the attention they deserve. However, he couldn’t predict that it would be a woman!

Smith’s handwriting is a little challenging to read, so I certainly do have my work cut out for me. But I look forward to spending the next few months with Fred Smith, and helping everyone else get to know him better too.

Lorna