30 – Letter to Frederick Smith from Fred Bullock, 1 May 1914

The copyright of this material belongs to the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons. It is available for reuse under a Creative Commons, Attribution, Non-commercial license.

Help more people find this work! Suggest a tag via the form:

Help more people find this work! Suggest a tag via the form:

“Sore backs appear inseparable from mounted service, they have existed as long as the horse has been used in war … it was reasonable to suppose … as knowledge advanced, a reduction in this class of injury should have been possible.”

So says Frederick Smith in his book A veterinary history of the war in South Africa 1899-1902 (item id 003722) in the section on the history of sore backs. He then goes on to claim that in the 40 years following the Battle of Waterloo all “the lessons of war appear to have been forgotten.”

Later campaigns meant that the topic became a matter for discussion again. In the early 1880s General Sir Frederick FitzWygram, Commander of the Cavalry Brigade, studied the problem showing that it was often the construction of the saddle that was to blame.

The topic then became the subject of a series of lectures, delivered by Smith, at the Army Veterinary School in Aldershot. These lectures were eventually published in 1891 as A manual of saddles and sore backs (item id 26542).

The manual is set out in four sections: the first covers the anatomy and physiology of the back because, as Smith states, “no accurate conception of the fitting of a saddle … can be formed until we have some knowledge of the structure on which the saddle rests.” This is followed by 16 pages on the construction of a saddle, 8 pages of instruction on how to fit one properly and finally 17 pages on ‘sore backs – how they are caused, prevented and remedied.’ The book contains 11 illustrations – 6 are anatomical, 5 on fitting a saddle with the final one showing the sites of the various injuries.

In spite of the lectures and manual it would appear that little changed – when referring to the South African War Smith states that “sore backs represented one of the chief causes of inefficiency.”

This view is also expressed by William Snowball Mulvey in his little (20 page) book Sore back and its causes in army horses on a campaign (item id 26379) which was published in 1902. Sore backs had been the topic of Mulvey’s RCVS Fellowship Thesis and one of the reasons for this choice was “The fact that nine out of every ten cases which came before my notice in South Africa were the so-called sore backs.” By publishing his thesis Mulvey hoped to make his observations more widely available.

The book is very much a practical manual – it identifies 9 causes of sore backs and then shows how to prevent the injuries occurring in the first place – as Mulvey says in his closing words “the rational treatment of sore backs, is of course, the removal of the cause.”

Interested in finding out more? The notes and illustrations Smith made when carrying out research for his lectures and manual form part of the Frederick Smith Collection , they provide a fascinating insight into the meticulous way Smith carried out his rearch on this topic.

References

Mulvey, William Snowball (1902) Sore back and its causes in army horses on a campaign . Fellowship theses later published by H & W Brown

Smith, Fred (1891) A manual of saddles and sore backs London: HMSO

Smith, Frederick (1919) A veterinary history of the war in South Africa 1899-1902 London: H. & W. Brown

There has been a lot of discussion of anatomical illustrations recently following the opening of the exhibition at the Queen’s Gallery Leonardo da Vinci anatomist. We have a number of stunning anatomical illustrations in the Historical Collection – the most well known would be in Stubbs’ The anatomy of the horse and then there are those in Carlo Ruini’s Anatomia del cavallo, infermita, et suoi rimedii and Andrew Snape’s Anatomy of an horse.

Although I admire these works my favourite anatomical items are the books of models that we have. Turn the page and lift the flaps to see what lies behind – it is like being a child again.

We have two complete series of these ‘flap books’: Vinton’s livestock models – which includes the pig, the sheep, the bull, the cow, the horse, and the mare and foal and Philips’ anatomical and technical models, series 2.

This second set by Philips covers domestic animals. Again we find the horse, the ox, the sheep and the pig but interestingly we also find the dog. Why interestingly? Well these books were produced in the 1890s, a time when the practice of keeping a dog as a companion animal was not common.

The dog: its external and internal organisation: an illustrated representation and brief description was edited by Alexander Constant Piesse MRCVS who graduated from the Royal Veterinary College in 1885 and the anatomical description is by William S Furneaux.

It starts with a 28 page text which gives the general characteristics of dogs, then divides dogs into two types – non-sporting and sporting and gives the characteristics of the main breeds. This section is illustrated with some rather nice images.

There then follows “a detailed account of the anatomy of the body of the dog; [which] will be illustrated by means of a folding model of the St Bernard”. The various ‘layers’ are then discussed – starting with the exterior, the skin, and ending with the genital organs.

Finally, there is an explanation of the folding plates with each section numbered to correspond to the model. So we have: Head – (1) Nose (2) Crest of nose (3) Mouth and upper lip etc

There are 5 folding plates in all – and you lift the flap to reveal the next ‘layer’. The inner ‘layers’ are a mass of flaps – so much so that instructions are given as to how to open them “No 13 [left lung] may be turned upward and 18 [left ventricle] to the left …the interior of the hear them become[s] visible”.

Please get in touch if you want to visit and explore the layers of the dog – or horse or pig ….

I thought before I leave my role here, and go off to study for my MA in Archives and Records Management, it would be a nice idea to share snippets of my favourite finds and favourite materials that I’ve had the pleasure of working with during my time with RCVS Knowledge’s historical collections.

For those of you who also follow us on social media you might be aware of some of the fun we’ve had using hashtags whilst photographing our daily finds and tasks.

I have enjoyed never having to beat the Monday blues whilst I’ve been working here. In fact Mondays have been every colour imaginable and I’ve been celebrating that with #marbledmondays on our Instagram account

Highlights of our #marbledmondays photographs on Instagram

It didn’t stop with Mondays – #tinytuesdays, #waybackwednesdays, #throwbackthursdays and #finebindingfridays, have all allowed me to engage with our library and archive collections in new ways, and of course, to show them off!

More photographs showing off our collections!

I have also adventured to far-flung lands alongside fascinating people, such as Captain Richard Crawshay, who authored the book The Birds of Tierra del Fuego (published in 1907). His letters are now transcribed and can be viewed via our Digital Collections website here.

Page from letter to Frederick Smith from Richard Crawshay, Useless Bay [Inutil Bay], Tierra del Fuego, [Chile], 29 Jan 1905 [FS/3/3/3/1]

This is one of my favourite quotes from Crawshay’s letters (pictured above):

“The most sensational birds I have – to me at least are a tiny Reed Warbler no larger than a Bumble Bee, a tiny black wren from the depths of the forest at the entrance of Admiralty Sound, a tiny tiny owl from the forest weighing exactly 3 oz, probably the largest bird of prey in the island – an Eagle measuring 5ft 91/2 inches from wing tip to wing tip…”

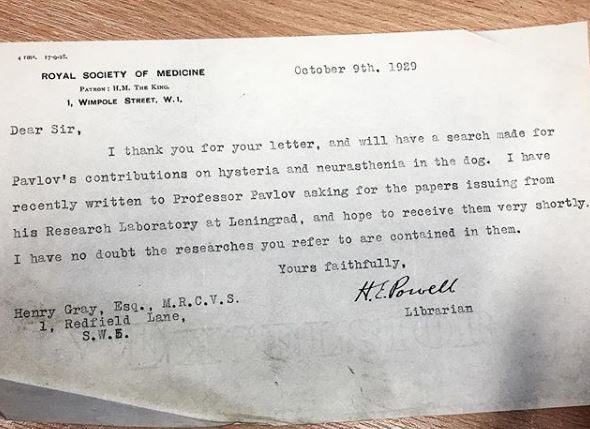

One of my favourite people to get to know was Henry Gray, an early 20th century veterinary surgeon. I am cataloguing his papers and have learnt so much through the words of his correspondents. Henry Gray’s papers have given me a great insight into the plight of the veterinary professional in the 1900’s. Through Gray and his peers I have learnt about the veterinary surgeon’s tremendous work ethic and their incredible anatomical, clinical, pathological and physiological knowledge. One of the most interesting letters I found in Gray’s papers was one where he had a response from a librarian from the Royal Society of Medicine after requesting Ivan Pavlov’s research into canine hysteria and neurasthenia. It put Gray’s life into a greater context for me – imagine being able to reach out to Pavlov himself for your own research?

Letter to Henry Gray from H E Powell, Librarian, Royal Society of Medicine, 9 Oct 1929

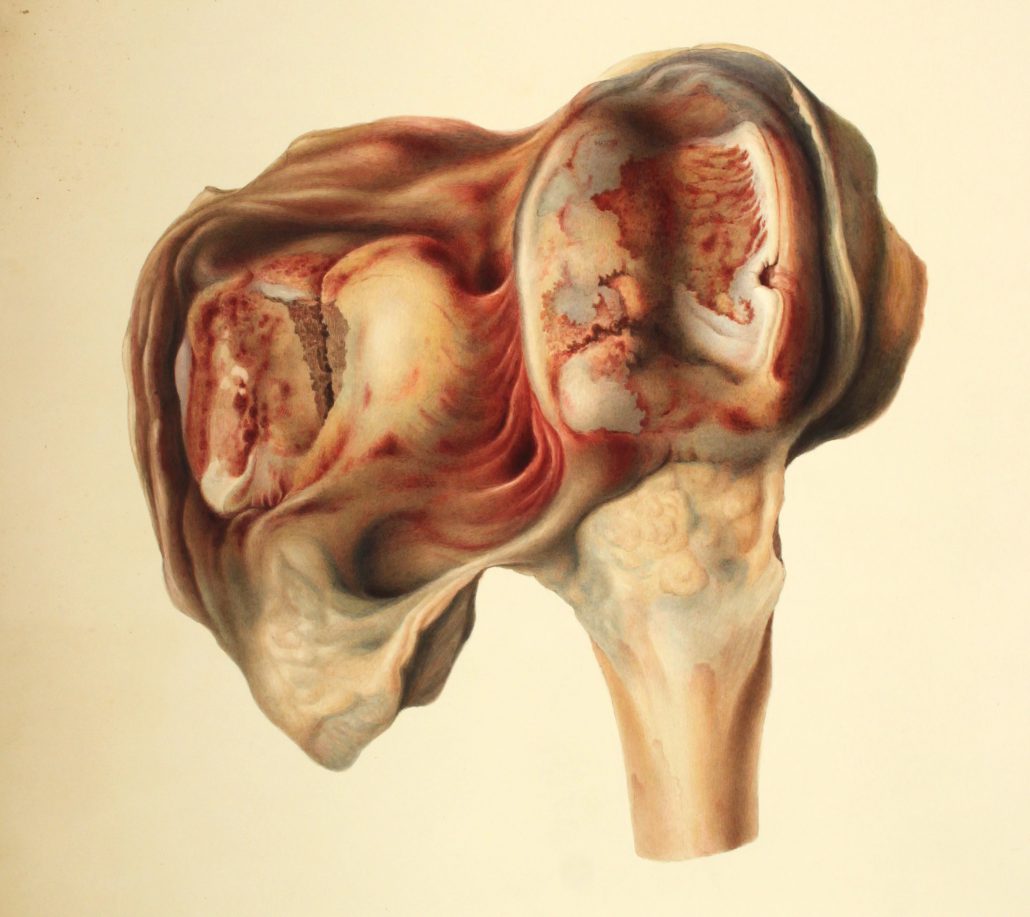

The most recent exciting discovery was a batch of finely detailed 19th century artworks which the archivist found tucked away in a cupboard. The pieces have now been carefully restored and we have an online shop where you can pick up a select few as prints! (You can visit the shop here: shop.rcvsvethistory.org) I enjoyed getting to digitise these amazing paintings and drawings, even though the art is as equally beautiful as it is grisly! Ovet the next few months, we are going to be asking our Instagram and Twitter audience to help us identify the parts of the anatomy we can’t, so stay tuned for that! There are many other amazing artists in our collection and it was interesting for me to find out that some of them had actually practiced as veterinary surgeons too, such as Edward Mayhew and John Roalfe Cox.

Anatomical artwork by Joseph Perry, January 1835. From the Field Collection.

A page from John Roalfe Cox’s sketchbook

Thank you to everyone who has been following along with us. I have had so many great experiences in my time working for RCVS Knowledge. I’ve been here over a year and there is still so much more to discover. I’m so glad to have had a hand in sharing the important historical value of such an amazing profession.

-Helena-

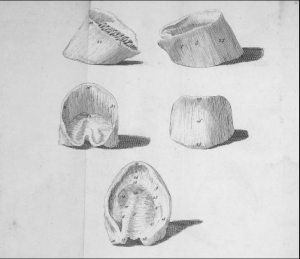

Bridges’ diagram entitled Explanation of the Five Views of the Foot

This illustration comes from the book No Foot, No Horse by Jeremiah Bridges, first published in 1751 by J Brindley of New Bond Street, London. The illustration shows the locations of thirty-two common complaints suffered by the horse’s foot. These include disorders such as Sand Cracks, Channel-Nails and the horrendous sounding Loosened Hoof. It’s thought that with this publication Bridges became the first Englishman to fully describe the anatomy of the horse’s foot. Bridges is also believed to be the first to precisely define navicular syndrome, a disease of the navicular bone and surrounding soft tissue which could ultimately cause a horse to go lame.

In his preface Bridges outlines the purposes of the book. He begins by explaining the anatomy and physiology of the foot. This he does under twenty-six headings, each covering a different anatomical part such as Os Imum Pedis, the pedal bone, Ligamentum Annulare, the annular ligament and Venae, the veins. Following this Bridges discusses the various types of feet, explaining differences in colour, shape and consistency, plus his thoughts on regional variations. Finally, he gives an account of common diseases of the foot and his suggestions for remedies. Many of these medicines came in the form of powder balls – cholic ball, fever ball, etc. To make these into a paste Bridges recommended using what he describes as “fresh, wholesome human urine”. A strange solvent perhaps, but Bridges declared it beneficial for the delicate salts it contains, the acidity of which accelerates the work of the medicine by stimulating the stomach.

No Foot, No Horse includes an advertisement for Bridges’ medicine shop in Orange Street, Westminster

Little is known of Bridges’ personal life, such as his dates of birth and death, details of his family or his origins. Professionally, in No Foot, No Horse, he describes himself as a farrier and anatomist, and we know he had a medicine shop, as this is advertised towards the end of the book. Frederick Smith in his 1923 book The Early History of Veterinary Literature Volume 2 states “…his work bears evidence that he was not an armchair author”. Smith verifies this by stating that the structure of Bridges’ book “…was put together in his odd moments”; that his writing work had to fit in around his day job. The book’s anatomical dissertation is a result of Bridges’ own dissections (in the preface he states “I have faithfully followed the knife, not pinning my faith upon another’s sleeve”), and it is believed he presented an annual course of lectures on the subject of horse anatomy, possibly delivered on his shop premises.

His shop was located at the Bucephalus Head, on Orange Street, Westminster – Bucephalus being the name of Alexander the Great’s horse. Bridges’ name does not appear in the volumes of property rate books for this period held at the City of Westminster Archives. This suggests he leased rather than owned his premises. Orange Street would have been an ideal location for a shop specialising in the treatment of horses. Neighbouring to the north was Leicester Fields (now Leicester Square), an area of wealthy townhouses, including the homes of artists William Hogarth and Joshua Reynolds. We can assume the affluent inhabitants regularly used horse-drawn transport.

To the south of the shop was the Great Mews which occupied what is now Trafalgar Square. This was the meeting point of several major roads, and, as with today, it would have been a busy centre for traffic. Indeed, part of this mews was taken up by an extensive stable block, described by the writer James Ralph as ‘…a very grand and noble building’ in his 1734 work A Critical Review of the Public Buildings. Bridges’ shop therefore had wealthy people and their horses to the north, and a busy passing place for equine transport to the south. The hubbub of horse-powered London was all around him.

Not all Bridges’ advice in the book required the purchase of medicine, despite the fact that such sales must have made up a good proportion of his income. In No Foot, No Horse, he is critical of those who “…practice by rote, and give doses prescribed by a recipe stuffed with ingredients they know not the nature of.” Many of his recommendations lean more towards nutrition. For horses suffering fever he suggests a diet of flags (yellow irises) and grain (“I have known several horses cured by this regimen, with very little assistance of medicine.”). Similarly, horses suffering from distemper should be fed gruel or milk pottage to give them strength. Bridges recommends keeping the gruel warm by storing it in a stone container and leaving it inside a warm dunghill.

Smith describes Bridges as being without cruelty in his treatment of horses, that he “…refers in feeling terms to his patients”. Bridges was opposed to excessive bleeding at a time when the technique of venesection was common practice, and advocated the importance of good standards in nursing, saying we should accept no excuses for its neglect. Smith sums up Bridges by saying “His observations on purging, bleeding, nursing and the avoidance of drugs do honour to his judgement and wisdom” and he considers Bridges to be “…too advanced in his views to influence public opinion, and his work would probably have been of greater effect had he lived forty years later.” This perhaps explains why No Foot, No Horse ran for only two editions (in 1751 and 1752). Indeed, Bridges intended to write further volumes, concluding his preface with the hope that “If this essay meets with a kind reception, I propose going through the whole anatomy.” Sadly, these additional books seem not to have materialised, and his great ambition was thwarted by an industry unwilling to subscribe to his forward-thinking theories.

Bridges’ book is available to read here: https://vethistory.rcvsknowledge.org/bridges-jeremiah-no-foot-no-horse-an-essay-on-the-anatomy-of-the-foot-of-that-noble-and-useful-animal-a-horse-1752/

We are an RCVS Knowledge initiative, for the preservation and promotion of the historical collections of the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons, made possible with the support of The Alborada Trust.

The Alborada Trust is a charitable trust founded in 2001. Its aims are the funding of medical and veterinary causes, research and education – and the relief of poverty and human and animal suffering, sickness and ill-health. Charity Registration No 1091660

Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons Trust (trading as RCVS Knowledge) is a registered Charity No. 230886. Registered as a Company limited by guarantee in England and Wales No. 598443.

Registered Office:

First Floor, 10 Queen Street Place, London EC4R 1BE

Correspondence Address:

RCVS Knowledge, 3 Waterhouse Square, 138-142 Holborn, London. EC1N 2SW

020 7202 0721

This site uses cookies. By continuing to browse the site, you are agreeing to our use of cookies. See our cookie declaration

Accept settingsHide notification onlySettingsWe may request cookies to be set on your device. We use cookies to let us know when you visit our websites, how you interact with us, to enrich your user experience, and to customize your relationship with our website.

Click on the different category headings to find out more. You can also change some of your preferences. Note that blocking some types of cookies may impact your experience on our websites and the services we are able to offer.

These cookies are strictly necessary to provide you with services available through our website and to use some of its features.

Because these cookies are strictly necessary to deliver the website, refuseing them will have impact how our site functions. You always can block or delete cookies by changing your browser settings and force blocking all cookies on this website. But this will always prompt you to accept/refuse cookies when revisiting our site.

We fully respect if you want to refuse cookies but to avoid asking you again and again kindly allow us to store a cookie for that. You are free to opt out any time or opt in for other cookies to get a better experience. If you refuse cookies we will remove all set cookies in our domain.

We provide you with a list of stored cookies on your computer in our domain so you can check what we stored. Due to security reasons we are not able to show or modify cookies from other domains. You can check these in your browser security settings.

We also use different external services like Google Webfonts, Google Maps, and external Video providers. Since these providers may collect personal data like your IP address we allow you to block them here. Please be aware that this might heavily reduce the functionality and appearance of our site. Changes will take effect once you reload the page.

Google Webfont Settings:

Google Map Settings:

Vimeo and Youtube video embeds: