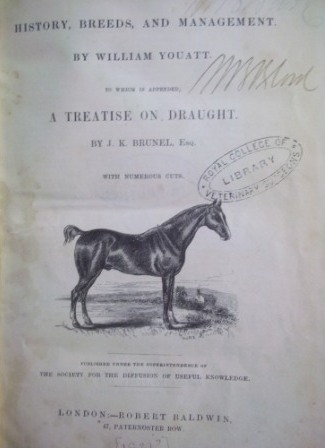

Equal Pay for Equal Work – Part 1

Part one of two guest blog posts from Julie Hipperson, PhD student at Imperial College London.

In February 1943, the Council of the SWVS were not surprised when their attention was alerted to the fact that the Veterinary Record was carrying adverts which offered different salaries for men and women. The issue of equal pay for equal work was by this time on the national agenda thanks to the efforts of women’s organisations such as the British Federation of Business and Professional Women, who had been spurred on by the reality that women being deployed into essential war work were receiving far less than their male counterparts, and due to the importance of the issue the adverts sparked a conversation within the SWVS about the suitability of adopting the principle of equal pay for equal work within the veterinary profession.

The widely-held opinion was that in small animal practices women should have similar salaries, and the general view was that in routine laboratory work women should be on the same scale as men. As such, the final resolution was that the Council would lodge a formal note of protest if a salary were offered on a lower scale for a woman. There was, however, dissension voiced over the issue of agricultural practice; as women could not lift heavy weights, the argument ran, they should have a lower rate in these type of work. This was disputed, some arguing that even male practitioners also required lay assistance ‘for the heavy jobs’, and due to the important nature of the debate, a survey was sent out to its members mid-1944. In total, it had been sent to 192 women, and they received a 35% response rate. Of the replies received, 57 had given an unqualified ‘yes’ to the question of whether women should receive equal pay for equal work. Eight, however, agreed in principle but were not sure that women could do equal work.

The issue of women’s strength was something which had been discussed during the debates on women’s entry to the profession, and would continue to be discussed, but what is interesting about this view of women’s pay in agricultural practice is that it links the issue of equal pay to a woman’s physical ability to do the job, rather than their intellectual ability. It becomes less a question of a right predicated on inalienable equality, a view the more strident women’s groups were voicing, and more a pragmatic assessment of their ability as women to do the job they were being asked to do. This could perhaps be characterised as striving for an equality of opportunity, rather than necessarily equality of pay.

by Julie Hipperson. Part 2 to follow.

Read more about the profession on our webpage, Capturing Life in Practice Follow Julie’s blog, Pioneers and Professionals