Our home on Horseferry Road – 100 years old today

Today we are celebrating the 100th birthday of 62-64 Horseferry Road, the current home of the RCVS.

The plaque on the corner of the building records the laying of the foundation stone like this:

“Mr Fegan’s Homes” (incorporated)

to the glory of God and the welfare of orphan,

needy and erring boys, here and

hereafter, the foundation stone of

this House of Mercy was laid by

the Right Honourable Lord Kinnaird

on

20th May 1912.

“His compassions fail not Lam. III 22 ”

Why ‘House of Mercy’? This was something that intrigued me and several other staff so the anniversary seemed like a good time to try and find out more. A quick search on the web revealed that the charity Fegans still exists today offering support to children and their families in South East England.

An email to them brought forth a wealth of fascinating material about the history of the building and its intended use. ‘House of Mercy’ refers to the fact that it was being built to house the new headquarters of “Mr Fegan’s Homes”, a shelter for homeless boys under 16 and a hostel for poor working boys.

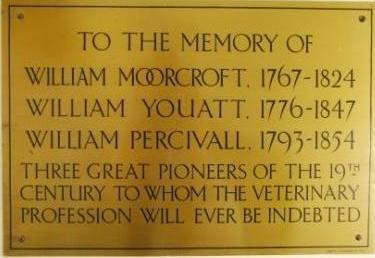

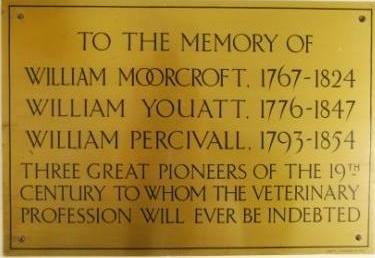

James Fegan (1852-1925) started his work helping street urchins a few years after he completed his education, founding a charitable society in 1870 and opening his first home in 1872. The society continued to expand and by 1912 was in need of a new building.

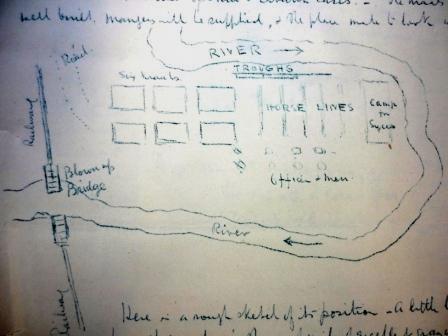

Loving and Serving (the society’s magazine) for March 1912 tells the story up to the point when the foundation stone was laid in May 1912 – a story full of trials and tribulations. It seems that, not long after they had completed the purchase of 87-91 Tufton Street, some of the frontage was requisitioned by the Council as part of a road widening scheme. This meant that 62-64 Horseferry Road had to be acquired as well to give them enough land on which to build – the whole (corner site) was eventually cleared for the new building in February 1912.

The building was to be called “The Red Lamp” – its red lamp, on the top most corner of the roof, would “shine night by night as a beacon of hope and help…”.

Loving and Serving May 1912 records the laying of the foundation stone by Lord Kinnaird at a ceremony which was attended by several prominent clergymen. The programme for the event had hoped for £3,000 in ‘gifts and promises‘ towards the cost of the building, but this was surpassed on the day when a total of £4,426 was pledged.

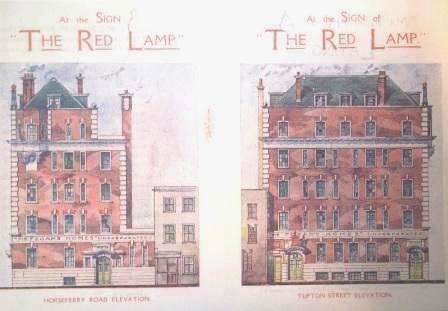

“The Red Lamp” was designed by AE Hughes and is described by Pevsner 1 as ‘free Neo-Wren’(1). The finished building was slightly different to that shown on the leaflet for the laying of the foundation stone – with two doors in Horseferry Road and only one in Tufton Street (the original plan had been for two doors in Tufton Street) , presumably this was due to the loss of frontage in Tufton Street.

The official opening was held just over a year later on 17 June 1913 . There was a public meeting at Church House, Westminster (just around the corner), then those in the crowd who had reserved tickets to view the building moved to Horseferry Road where the three sections of the building were declared open. The event is described in detail in the July 1913 issue of the Society’s magazine, which was now renamed The Red Lamp.

To give a flavour of the event – it was ‘a bright summer afternoon’ there was ‘sweet and effective singing’ and a ‘substantial Thank-offering, £837’. The only negative thing recorded was the theft of the caretaker’s watch!

Unfortunately the high hopes for “The Red Lamp” were curtailed by the outbreak of war in 1914, with the shelter and hostel closing at that time. The offices and advisory centre remained in Horseferry Road until the building had to close due to bomb and fire damage following an air raid on 16 April 1941. (The then RCVS building in Red Lion Square was also hit by a bomb, on 10 May 1941, and suffered similar damage).

If you are interested in finding out more about the work of Fegans today, please visit their website.

Images

All images were kindly supplied by Fegans who retain the copyright.

Reference

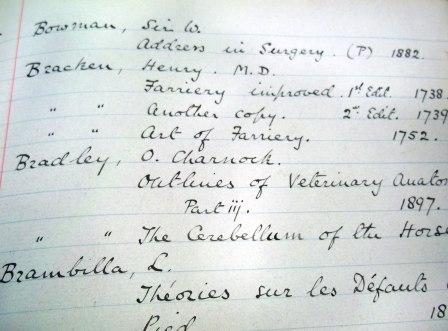

1. Bradley, Simon and Pevsner, Nikolaus London 6: Westminster (Pevsner Architectural Guides: Buildings of England) Yale Univ Press 2003