Your horse belongs to the army now – part one

The popularity of Michael Morpurgo’s book War Horse, the success of the stage adaptation and now the release of Steven Spielberg’s film has brought the role horses played in the First World War to the public’s attention.

Joey, the main ‘character’ of War Horse, belongs to Albert, the young son of a farmer. He is sold by the father, to a Remount Purchasing Officer on behalf of Captain Nicholls. Later, Captain Nicholls reassures Albert that Joey will be looked after, even though “your horse belongs to the army now”.

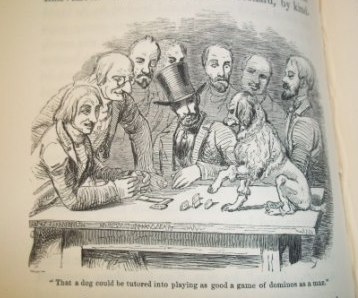

In the RCVS archives there are two paintings of the heads of horses that were acquired by the Army Remount Service, the department that purchased horses for the army, during First World War. The two horses spent time at Romsey Remount Depot during 1916, where they were painted by Lionel Dalhousie Robertson Edwards (1878-1966). Edwards served as a Remount Purchasing Officer in World War One and was to become a well known sporting artist in later life.

The depiction of Joey’s purchase by the army in War Horse could give the impression that the acquisition of horses for the war effort was a small scale operation – in fact nothing could be further from the truth.

For our next post, we’ll be delving into the requisitioning of horses during the First World War and the history of Romsey Remount Depot, where Edwards served, and its veterinary hospital

The two paintings, along with other items connected with the role of horses in war, are currently on display in the Library. Why not come and see them and combine it with a trip to the excellent exhibition War Horse: fact and fiction at the National Army Museum?

Image: Paintings on display in the library