Reading for Pleasure

Today is World book day. Some of us will remember the £1 book tokens given out at school, picking out our favourite book at the book shop and rushing home to read it– today is definitely a day for the bookworm! World book day is a celebration of illustrators, authors and, most importantly, reading.

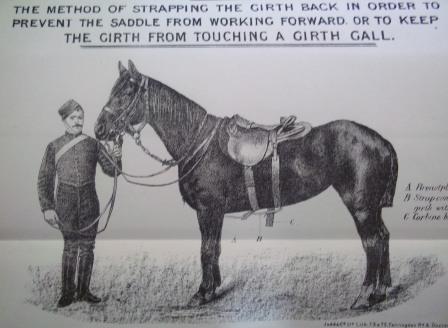

As a veterinary library, we are mostly visited by vets and veterinary nurses doing personal research. We would love for more of our library users to while away the hours in our Historical Collection, reading just for the pleasure of it. Our Historical Collection contains some fascinating and important works that our users may not know about. Even without the veterinary background that puts the contents of our collection into context, I am still constantly surprised by the beautiful artwork or an old fashioned turn of phrase. Some of my favourite pictures and extracts make a weekly appearance on our Twitter feed.

Our Historical Collection contains some great material. George Stubbs’ (1724-1806), the renowned English painter of horses, appears in the collection. If early photography is more your thing, how about Animal locomotion an electro – photographic investigation of consecutive phases of animal movements ; 1872 – 1885 by Eadweard Muybridge, the man who proved a horse could fly? Perhaps 16th century country affairs is what interests you? The oldest work in our collection is a 1514 copy of the Libri de re rustica published by the Aldine Press in Venice, purchased by the RCVS Library in 1963 for just £25.

So if you are ever in London, stop by to read and explore our truly unique collection. We’re always happy to show it off! Please contact the Librarian, Clare Boulton, for visiting details c.boulton@rcvstrust.org.uk

Read more about how we safe guard our valuable collection, with our Adopt a Book scheme